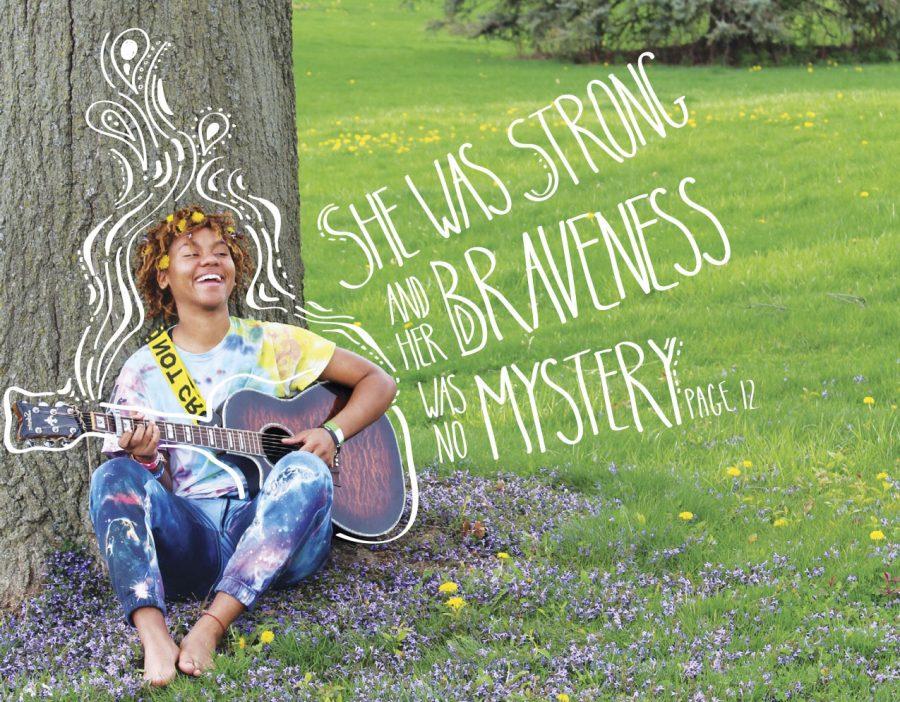

She was strong and her braveness was no mystery

Music is said to connect people in an unspoken way, and heal the soul through its expression of emotion and reality. Lexi Williams ’18 knows this healing process all too well. Her story is one of pain and hardship, but most of all it is one of triumph.

Williams’ story begins on the corner of 43rd and Cicero in the Chicago projects, where she lived from birth until age seven.

Her view out the window was what she describes as a “war zone.” The city has since torn down the crime-ridden projects, helping to diminish the violence, but not the memories.

“It was a fear living there. There were gangs everywhere. There were needles on the ground and blood spots,” Williams said. “We always had to hide. Our blinds had to be closed and we could never unlock the door unless it was our mom.”

The quintessential image of a child living the American dream is portrayed as playing in the front lawn with the neighbors and walking to the local pool in the summertime. Williams’ experience was much different, as playing outside was not always possible.

“We played outside only when our mom was out there. Sometimes our dad was there,” she said. “He was always in jail. We would see him and know he was out, and then when we didn’t see him for a while we would know he was back in.”

Despite living what can be considered an unconventional childhood, Williams also recounts memories that are ordinary and child-like. There was the time when she hid under the plastic swimming pool in her yard from a storm until her mom yelled at her, or the time her father bought her and her siblings bubbles to blow.

Williams comes from a tight-knit immediate family; one that has shared countless hardships and experiences. “I’d say we are closer than the average family. I didn’t know that a lot of people don’t sit together when they eat, but we always do that,” Williams said. “When we had nothing, we had each other. Now we have more things, which is bringing us apart.”

After moving out of the projects, Williams and her family found themselves without a home. On the nights they weren’t sleeping in their car, they stayed in church-run shelters; first in Arizona, then Minnesota and finally Illinois. For Williams, explaining the fact that she didn’t have a residence became a common occurrence.

“We were always looked at as dirty,” she said. “I don’t know if people knew we were homeless, but I hoped they didn’t.”

There was a set bedtime in the homeless shelter where Williams, her mother and her six siblings stayed—lights out at 8 o’clock. This meant no time for staying up to work on that essay due at ten, especially without a computer. Sometimes Williams and her family would go to bed hungry, but Williams says she was still grateful for the food they did get. If Williams’ sister didn’t want to eat something, they would trade and dinner would turn into a “big feast.”

Williams and her family eventually found themselves heading from Arizona to Minnesota in a $400 blue Dodge Caravan. While living in a homeless shelter in Minnesota, Williams learned to play the violin and read music. Her music teacher, Ben, said she was one of his best players.

“When I was going through stuff, all [my music teachers] would tell me not to stress about it and come to their rooms to play,” she said. “That’s probably why when I get sad I go to music first, or drawing or writing.”

One of William’s’ current teachers, Phil Keitel, admires her ability to use music and the arts as an outlet.

“She doesn’t fight back in a negative way. She writes poems, and I’m pretty sure she made a teacher cry with one of her poems,” he said. “That’s how she gets her emotions out. She doesn’t fight back in terms of violence or negative words, which is really new in kids today.”

When Williams and her family were forced to move again and drop everything but the clothes on their backs, she had no opportunities to continue her passion. Upon her return to Illinois, her cousin bought her an unexpected gift—a guitar.

“I never knew I was going to get a guitar for my birthday. When I looked at it I was like, ‘Oh, this is so foreign, what is that?’” she said.

Although for most of Williams’ life she was forced into moving to new places and experiencing new things, she feels as though it has shaped her into who she is today. She looked at the constant moving as a way to advocate for trying new things. Thus when she received the guitar, she was not afraid to pick it up.

“If I was comfortable with what I did and just sat at home and had the same exact life, there would be no spot for growing. I think you have to be uncomfortable and take a leap of faith to discover more things,” she said.

Williams turned to music and songwriting to cope with tragedy in her life, including being a victim of sexual abuse. From age 11 to 15, Williams and her two sisters were both sexually assaulted by a family member, and it wasn’t until her sisters came forward that Williams also spoke about the abuse she was experiencing.

“I was mad at him for what he did to my sisters, and I always acted like it never happened to me. I would try so hard to cover it up, and it got to a point where I believed it didn’t happen,” she said.

Her outlet became the arts, which she used to write and “let the words flow.” One of the poems she wrote expresses the weight and burden she carried as a victim of sexual abuse.

As hard as it seems

I spill from the seams

That they rip me out of

I’m free to be me

I’m free to Be

Yet no one understands

I flinch hard at hands

Held high above my head

I quiver

It’s not that cold so why do I shiver?

…

I have a body that is not mine

…

Am I the only one?

if a tree falls and no one is there to hear it, did it really fall?

if you steal a car and no one sees, did you really break the law?

When it happened everyday

you’re told not to stand up so tall

I fold in this so called life

I’m not sorry

The thought of me having a wife

brings strife to my mom

She says it’s because what happened to me

Depression in my body it was planted like a seed

Momma didn’t know

I was a cry for help

Momma didn’t know I was hurting myself

Momma didn’t know I was the story that fell off the shelf

Williams is far from being alone. As few as 3 percent of child victims of sexual abuse report their abuse to law enforcement, and 36 percent never tell anyone at all, according to a study by the Illinois Coalition Against Sexual Assault.

“I thought I was dirty and unworthy,” Williams said. “When I went to court for it I felt so much better; it was released off my shoulders. I felt like I wanted women to know that if they were [sexually abused], they don’t have to hide it, that just gives the person who did that to you more power. Just to have to go through that, it showed me that I was worthy.”

Williams developed post-traumatic stress disorder after her abuse. Her family’s desire to leave the house and place where it all occurred is another reason they moved to Iowa City.

“It’s hard because I don’t trust men, or people that look like him. It’s hard to talk to them. I hate that about me because I don’t like to judge [or] stereotype people,” she said.

Williams is passionate about being there for others and helping them through their hardships. She helped one of her friends who was starving himself to “get a little plump”, and writes poems to inspire people to persevere through hard times. This sense of duty she feels to protect others and make their days generally brighter proved to be the most difficult when it came time for Williams to talk about her experiences.

“When I had to tell [my mom], I couldn’t even say his name. It showed me how much power it had over me; and when I first told her, she was crying and I didn’t want her to hurt more,” Williams said. “I don’t like seeing people in pain.”

Williams’ mom, Danita Pfeiffer, accredits many of her own personal growth to Lexi.

“I have grown to understand so much through her struggle. She has help me to be a better person,” she said. “She is created to be a light in dark places.”

Williams’ vibrant and optimistic personality is also present in the classroom, where she always tries to make the day a little brighter.

“She draws murals on the board all the time. Generally her classes are more happy-go-lucky because she’s always in a good mood,” Keitel said

Being not only a survivor but also someone who hopes to “give speeches and inspire others”, Williams had some parting advice.

“Know it’s not your fault whatever is happening. The best thing would be to tell someone that you trust. It doesn’t have to be your parents or the police. Holding it in, it really eats you alive. Talk about it; don’t be ashamed of yourself because you didn’t do anything wrong,” she said. “Know that you’re not worthless—you are worthy and you are loved.”

Williams wants victims to know this isn’t just something you can keep inside. There are people to provide support, and ways to find help.

“No one wanted to listen to me, or was understanding. I always thought that I was alone. I want them to know they’re not alone, and there’s a lot of different ways they can cope instead of hurting themselves or wanting to die,” she said. “Mine was drawing. Draw it out, write about it. I used to hate writing until I put emotion into it; that’s when I noticed I come from emotion. I want them to know they’re not alone. They’re worthy, and it’s not their fault. They have power and they’re in control.”