Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

2016 Presidential Election: the discrepancy between electoral and popular votes

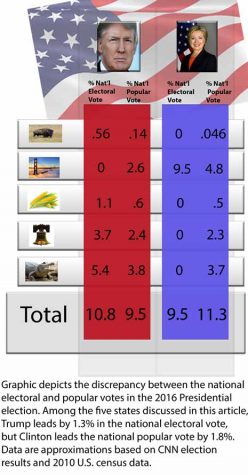

The discrepancy between popular and electoral vote allowed for Trump to win the 2016 Presidential Election.

December 13, 2016

One irony of the 2016 presidential election was that Trump, a critic of the electoral college system prior to the election, in fact, benefitted from the “rigged system;” in this election, the system was “rigged” in his favor.

Clinton won 48% of the popular vote, with 62,523,126 votes, overriding Trump’s popular vote count by 56,402,095 votes. Trump, however, won 290 electoral votes as opposed to Clinton’s 232 votes. So how, then, did Trump come to win the election? There is a common misconception that the number of electors in the electoral college perfectly aligns with a state’s population. To explain this misconception, it is best to go back to the start.

The framers, back in 1787, were almost completely in agreement that the electoral college process was best. At the Philadelphia Convention, the framers agreed that the selection of the president by Congress would make the president too dependent on Congress. Popular election was also deemed insufficient as it brought along baggage: suffrage requirements varied across states; and a national vote snuffed the voice of small states and southern states, where most of the population couldn’t vote.

When the framers eventually devised the electoral system, they created a foundation to protect the national government by placing a check on the people, and to protect smaller states. The framers feared placing the election directly in the hands of the people, lest they make an uneducated decision; they thus created an insurance policy of selecting a president based on their merits. Hamilton is attributed to saying in Federalist No. 68, “Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honors in a single state.” It would, however, take more than popularity to “establish him in the confidence of the whole Union,” to make him a “candidate for the distinguished office of President of the United States.”

Responsibility was given to the College because it was supposed to be a gathering of minds “most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station” and should choose some “fit person.” Despite the framers’ reservations about the American people, it was expected that the electors be elected within their state. This way, the people would get their voices heard in selecting the president.

The Electoral College system was developed to be a microcosm of the national congress; it mirrored Congress exactly. A state was (and is still) allotted electors based on the number of senators and representatives that it has in Congress. It is important to note that each state is given two senators, no matter the population of each state. This creates equilibrium between largely and less populated states. The number of representatives each state gets, however, is determined by population. In this manner, the number of electors per state in the electoral college, in fact, provides an advantage to smaller states. For example, Wyoming receives an automatic two electors for the two senators with seats in Congress. Wyoming also receives one elector based on its sparse population of 583,223 taken from a 2013 Census Bureau. Wyoming is therefore overrepresented in the electoral system. To further explain this point, Wyoming’s three electoral votes account for approximately .5% of the 538 electoral votes nationwide, and 1.1% of the 270 electoral votes needed to win the general election.

California, on the other hand, is allocated 53 electors due to its large population of approximately 39 million. The two electors given due to the two senators, thus brings the total number of electors for the state of California up to 55. This is all fine and dandy, but California’s 55 electoral votes, which amount to 20.4% of the 270 electoral votes needed to win the general election, delineate how California is actually underrepresented in the electoral system. Therefore a candidate can win by millions of votes in Illinois, California, and New York, and have those votes canceled by small margins in states like Wyoming, Mississippi, and, yes, Iowa.

This single discrepancy between the population and the number of electors allocated per state is what allows a presidential candidate to lose the popular vote but win the presidential election.

This single discrepancy between the population and the number of electors allocated per state is what allows a presidential candidate to lose the popular vote but win the presidential election.

One major benefit to the Electoral College is that it provides the opportunity for electors to make the best decision for their country based on events following the general election. “Let’s say that John Jones won a majority in the popular vote, but before he takes office, he ‘flubs the dub’,” James Leach, former member of U.S. House of Representatives from Iowa, now professor, said. “Perhaps he gets more controversial, maybe times and international affairs are tough. After the election, it’s revealed he’s a crook, or that he’s had a massive heart attack, or that war broke out. Maybe his opponent has experience in the military field.” The Electors may be strongly inclined to cast their votes for Jones’ opponent.

“The Electoral College as such isn’t the problem,” Paul Gowder, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Iowa, said. “The basic idea of the Electoral College is a layer of deliberation between the public and the awesome power of the presidency. Sometimes mass votes are swept up in chaos and hysteria, and when that happens, it’s all too easy to lose constitutional democratic institutions. In those situations, it’s the job of the Electoral College to step in and preserve the Republic.”

Caroline Tolbert, Professor of Political Science at the University of Iowa, stated that while the Electoral College process is not undemocratic, it does provide odd outcomes. “We have a plurality, winner-take-all system,” she said. “And the cool thing is that we’re the only country to have this system.” Just like any board game, she said, there are a million ways to count votes. “Democracies have a huge variety of rules. Some have a majoritarian system, and many western democracies have proportional representation systems…legislators are elected in larger member districts, and the number of seats a party wins [in an election] is proportional to the voter support.”

Tolbert stated that many democracies had deliberative bodies composed of the highly educated or wealthy landowners. These people usually had similar policy goals and things they sought in a president that didn’t reflect the commonweal; England employed the House of Lords, which was, for a time, composed only of landowning men. Tolbert emphasized that times bring (and call for) change; for example, African Americans and women were given the franchise in the past 100 years.

Tolbert related the 2008 Iowa flood to political change. “The thing about the flood of 2008 is that it was said to be a ‘100-year flood’, but then five years later it happened again,” she said. “So-called 100-year floods seemed to be turning into far more frequent occurrences.” The political landscape is always subject to change, she continued. “There was a time when non-whites couldn’t vote, slaves couldn’t vote, women couldn’t vote. The law of the land is that change is like the 100-year flood.” With the uncontrollable changes time wrings, she says we have to “think carefully about a new plan [and] whether we should change [this one].”

The National Popular Vote Plan, which is an interstate compact plan, is one option to circumvent the amendment process to the constitution. This is one of the major appeals to the national popular vote plan; it does not require the ⅔ vote in the House and Senate and ¾ ratification in states to become implemented. “This plan,” Professor Leach said, “where states cast [their electors] based on the national popular vote is indirectly direct.” Some, he said, would claim this plan is illegitimate as it’s not passed through a constitutional amendment. The drawback is that it would eliminate the need for candidates to campaign in smaller states, such as Iowa. These states would no longer feel an empowered circumstance.

In any event, different times may call for different measures. The U.S. system, which uses indirect elections that funnel through a deliberative body which selects the president, may not be appropriate anymore. Perhaps in the upcoming years, the U.S. will witness changes to the way we elect a president.