Ed Barker

Of the dozens of perspectives we could use to analyze these last 50 years at West, the principal’s point of view gives us a sneak peak into all aspects of life at our school. Our three kings - Ed Barker, Jerry Arganbright and Gregg Shoultz - share their experiences at West and their contributions to the school. Hear from Ed Barker, principal at West from 1968 to 1979.

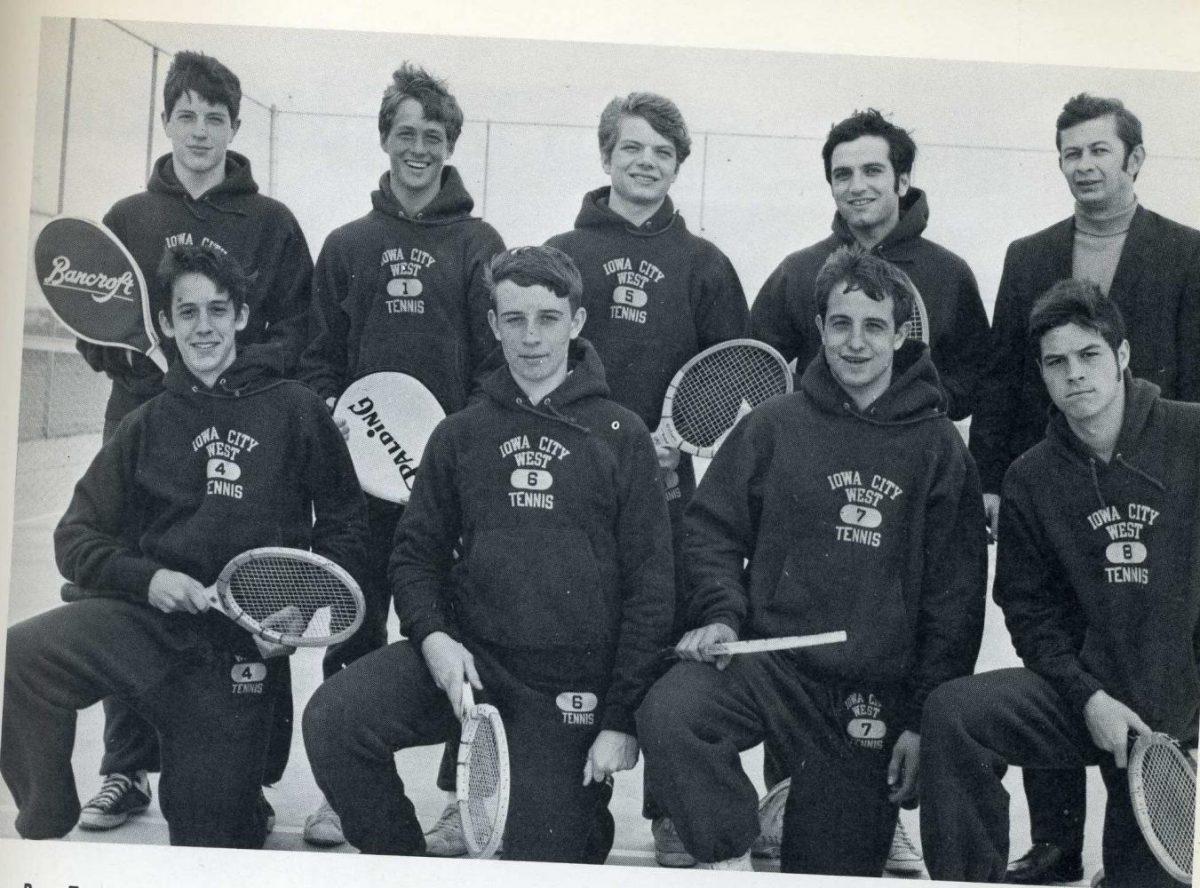

“I remember the first comment I made to the student body: ‘Welcome to the only high school in the state of Iowa undefeated in any athletic team there,’” Barker said.

It’s been 50 years since those very first words and although West is no longer undefeated, Barker’s attitude of success remains at West.

The school opened in 1968 to a worrisome start; the district ordered the City High students living in the West High district to transfer to this new, unfamiliar high school. The students in the Class of ’69 who were forced to come to West were unhappy about the decision.

To remedy this, Barker made sure that any and all students, whether hyper-advanced or on the verge of dropping, felt involved in academic life at West. For the advanced students, he brought AP courses to the school, beginning with AP English. But Barker says that it was his work with the other end of the spectrum, with students who weren’t academically accelerated, that he felt most proud of in his time at West.

“We had students who didn’t have a love for school,” Barker said. “I wanted them to have a good education, and so we were in what was called Room 20. They had regular classes and they were in there half the day with a special teacher to work with them on an individual basis. That was a really good move.”

Barker frequented Room 20 and said that he got along with the students very well. When he looks back on his experiences with the students, he says “they weren’t real troublemakers.” His relationship with the students grew to a point where Barker felt comfortable taking them on a trip across the country. He and five students from Room 20 went to Lincoln, Nebraska to visit the Governor’s Mansion; then down to Abilene, Kansas for a tour of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Museum and Boyhood Home; and finally travelled a little ways to Independence, Missouri to take a look inside Harry Truman’s childhood home. Barker recalled the trip vividly.

“We stayed overnight near the Eisenhower place. We slept in a tent, they went fishing, I cooked the fish, and that’s what we had for supper,” Barker said. “Those folks remembered that trip for a long time. It was real good for them.”

Soon after the vacation, Barker realized that Room 20 might be too small for what his students needed. He pushed for the construction of what was then known as the Community Education Center. A place that expanded the experience in Room 20 to a wider array of students, the center grew until it became a high school of its own, now known as Tate High.

“And it all began in Room 20,” Barker said.

Barker’s positive relationship with the students at West wasn’t exclusive to the students in Room 20. In fact, Barker’s philosophy was to move away from discipline and punishment, making him popular among the students and community.

“I didn’t want to have anybody be looked at as a chief of discipline,” Barker said. “We were going to put a lot of emphasis on student government, so we got off to a good start with sponsoring the Student Senate.”

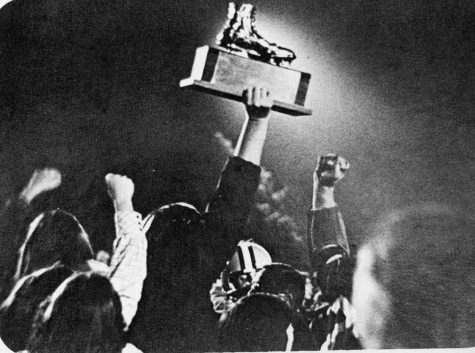

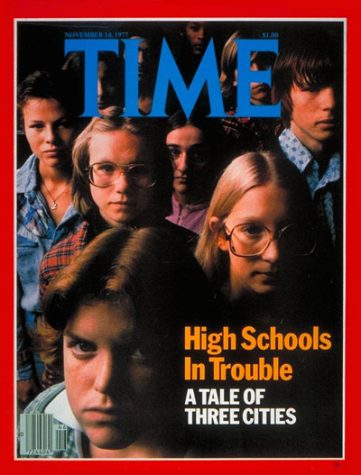

Barker’s administration and the Student Senate worked together to shape student life at West. Barker remembers a Student Senate organized the Barn Dance that was popular among students, and recalls that he himself square danced at the Barn Dance at one point. He tried to balance the fun and games with limited discipline, adding that “the administration was still in control.” Barker didn’t allow an open campus, and notably suspended the football players after a drinking scandal in 1971. His innovative disciplinary methods were featured in a 1976 issue of Time Magazine entitled “High Schools Under Fire.”

In addition to the innovation when it came to discipline, Barker was innovative when it came to teaching, a lot of which involved sparking debate through controversial speakers. In one of the first controversial instances, Barker invited a Vietnam War turncoat, someone who switched to the other side during the war, to speak to the student body.

“That started a big controversy and many people didn’t like it. But I did,” Barker said. “So, we tried to get controversial speakers, and we had many speakers come and speak to the student body.”

In a similarly polemical moment in the late ’60s, Barker decided to invite black speakers and white supremacists during Black America week following the Civil Rights Movement.

“We were always starting up a little controversy,” Barker said.

After 11 years as the principal, Barker finally decided to step down and go into real estate. However, Barker’s contribution to West High didn’t end there; in 2012, the eponymous Barker Field was created following Barker’s $270,000 donation to the school. The money was equal to the salary that Barker earned in his time at West. To this day, Barker is still one of West High’s notable benefactors. When asked for the reason why he felt such devotion and generosity to the school even 50 years later, Barker’s response was simple: “Having the opportunity to be directly involved in developing the best high school in Iowa.”