Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Voices from within

February 22, 2019

An identity crisis

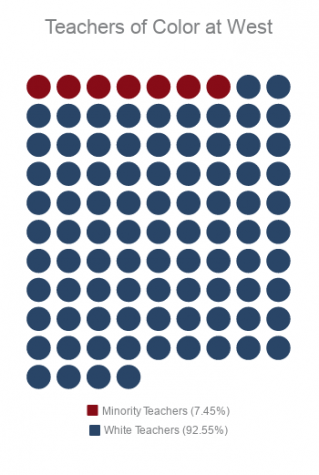

When English teacher Nate Frese walks into a faculty meeting, he blends into the predominately Caucasian crowd. With a lighter complexion, it is no surprise that he is mistaken as white by students and teachers alike. Many don’t realize, however, that he is one of only seven minority certified teachers at West High.

Identifying as Mexican-American, Frese often questions if discussing his heritage is relevant in a classroom setting.

“I wrestle with this,” Frese said. “It’s not like I’m hiding anything about who I am. … It’s something that I’m proud of and I’m aware of and I own, but at the same time, I’m not trumpeting it.”

Minority teachers may face this internal dilemma, especially if they do not teach a subject involving frequent student discussion.

“I have a lot of pride in being Asian-American, but I don’t think I get to express that very much as a math teacher,” said Tiffany Chou. “This is something I could work on … to build better relationships. I have had students light up when they hear a little bit about my ethnic background.”

Originally from Southern California, Chou grew up in one of the largest Asian populations in the country. However, this was not mirrored in terms of her teachers, as she cannot recall having “very many” Asian teachers or Asian students in her classes while studying to become a teacher.

Similarly, Frese does not recall having any Hispanic teachers. Because of this, he believes having a teacher he could identify with on an ethnic level would have made school a more enjoyable environment.

“When [I was] younger and trying to formulate my identity, boy wouldn’t it have been a bit more comforting to see a few more Latino males on my teaching staff,” Frese said. “Maybe I never would’ve gone and talked to them, but just to know that they were there, I think, would’ve put me in a better mindset about certain elements about school.”

Cultivating connections

Asian students often lie under the radar when it comes to racial inequity discussions. However, climate survey data revealed that Asian students are the least likely to report having an adult at their school that they trust and go to for advice.

“If I were to have an Indian teacher, it would be easier to talk about things like a [Bollywood] dance performance coming up the next weekend, or what I would be doing during my upcoming trip to India,” said Niyati Deshpande ’21. “The connection would be better, and there would just be more of an understanding.”

As a teacher, Frese also feels he can better connect with minority students. Throughout both his English teaching and basketball coaching careers, he has conversed with students who felt less alone due to having a minority mentor they can rely on.

“To know that there’s somebody else that went through something pretty similar and to see somebody like that, there’s a kind of calm and a release,” Frese said. “It’s like, ‘Okay, I’m not completely on an island here, and it will be okay. Here’s somebody that made it through that and [came] out the other side.’”

As one of the few African-American educators at West, science teacher Maureen Head has made personal connections with black students because of certain shared experiences that come with growing up black in America.

“I would never claim that there’s a monolithic black experience or monolithic biracial experience, but … there are certain shared experiences that we assume the other person has,” Head said. “Those shared experiences and those shared traumas [can] lead to a bigger sense of comfort when the students are talking to me.”

Tiffany Chou, a math teacher, identifies as Asian-American

African-American students like Ariana Moffett ’19 and Julian Jordan ’21 are just two of the many students who feel more comfortable coming to Head with their problems.

“She understands us,” Moffett said. “And she knows where we’re coming from because she in her life went through the same problems that we did. She can relate to us better than most other teachers could.”

“I felt like I’ve connected with other teachers on a personal level, but with her I feel like us both being biracial [created] a deeper connection,” Jordan said.

Head said that there are times when students come to her about racially insensitive comments made by teachers that the students don’t know how to respond to.

“I think sometimes the kid is venting and they just maybe need a place to process,” Head said. “Sometimes they’re looking [to tell someone], ‘Hey this was a really big deal, and something needs to be done about it. And what sort of steps do I take to make a difference?’”

Like Head, Northwest Junior High language arts teacher Amari Nasafi has taken personal experiences and translated them into interactions with African-American students and parents. For example, because he has a brother that was incarcerated multiple times, he’s connected with parents who had similar histories.

“I’ve had several African-American black students who have had situations that come up that I can connect with because we share that kind of background,” Nasafi said. “It’s not that I have any special knowledge, but sometimes when people find that out about me, it opens them up more. They don’t feel like I’m judging them, and that’s a huge hurdle.”

There are also some minority students who believe that while diversifying teaching staff is important, they have not personally felt disconnected from teachers based on race. Asian-American student Julie Shian ’20 believes that a teacher’s race is not as important to her as the effectiveness of their teaching.

“What’s most important is that a teacher makes an effort to try to help a student learn in a way that is best for them and makes their room approachable,” Shian said. “As long as teachers make efforts to make their students feel like they are in a comfortable learning environment, the connection is there.”

Suppressing stereotypes

When a student requires help in school, the first person they traditionally turn to is their instructor. However, for Robert Hooks ’20, this isn’t always the case. As an African-American student, he said he doesn’t want to perpetuate the stereotype regarding black students being “dumb,” so he prefers not to ask Caucasian teachers for assistance.

“I personally find it easier to seek help from a teacher who is African-American, because if I don’t understand something, I know I won’t be just another dumb black kid in their eyes,” Hooks said. “They truly want to see me succeed because they want me to be better than what society says I can be.”

Research done by Johns Hopkins University in 2017 concluded that if low-income black students have at least one black teacher in elementary school, they are significantly more likely to graduate and consider post-secondary education.

Another reason Nasafi can relate to black students is because he understands the stereotypes that they have to overcome and often faced similar ones growing up. According to Nasafi, the stereotype for African-American men is underperformance in school, so he felt that some teachers were taken aback by his interest in learning.

“It would creep into my mind sometimes whether I was performing really well or if they saw a young black boy who was interested in books, so they were encouraging me by being softer on me. I wanted to do well on my own merits, not because I was a representative of an underrepresented minority. I try to be like that as a teacher, too.”

The district climate survey showed that approximately 65 percent of black and multiracial students report that people at their school acted as if they were not smart. Jordan, who identifies as biracial, feels that this is true with teachers as well as students, as he believed teachers had lower standards for him because of his race.

“I feel like it can come out of good intentions, … like some teachers will go out of their way to help students because they feel like they’re not intelligent enough to get it,” Jordan said. “But I feel like there are some teachers who do have low expectations for minorities.”

There are also students like Moffett who feel that negative stereotypes against African-American students perpetuated by students and teachers discourage students from seeking success.

“It’s kind of hard for someone when everyday you have to be strong and try to fight [stereotypes],” Moffett said. “After a while, everyone has a breaking point. So when you meet that breaking point, you want to fall into that stereotype, like, ‘Okay, I’m going to drop out. They expected me to do that anyway.’”

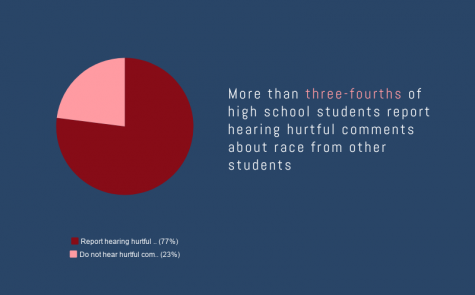

Moffett also cited several instances when teachers directly discriminated against African-American students based off of stereotypes of black students not being as well-behaved. There were multiple times when she or her friends were stopped in the hallways by teachers and questioned about where they were going, while non-black students did not receive the same treatment.

“Everyday I feel like I’m fighting a battle that I’m not going to win,” Moffett said, “because there are so many stereotypes against me.”

Because of instances like this, Moffett firmly believes that incorporating more minority teachers into the district would improve experiences for African-American students in particular.

“You [would] have more students opening up to teachers, telling them what their problems are and just feeling that there’s someone they can connect with, someone that’s on their side,” she said. “Everyone needs someone in their corner.”