Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Consequences of cows

March 5, 2020

In 2018, the ICCSD used 31,278 pounds of beef, which amounts to over 500,000 pounds of CO2 emissions. (Source: Alison Demory)

Blazing fires in the Amazon Rainforest are putting vast areas of unique ecosystems at risk, and some say this destruction is all because of cows. With the Amazon in flames, a question is being raised over whether cattle farmers are to blame. Afterall, it is no secret that farmers and ranchers have been burning down large sections of the Amazon for years to raise livestock. With methane levels soaring in recent years, many have questioned whether eating meat is worth the price of an increasingly warming world.

For the ICCSD, the answer to that question is yes. Alison Demory, Nutrition Services Director for the school district, is in charge of overseeing all aspects of the department, from meal production to recipe planning.

“I’m not sure at what point environmental reasons would ever become the sole decider of the menu,” Demory said. “I don’t anticipate that it would, quite frankly. Because if I don’t serve any kids, if [the majority don’t] want the plant-based options, then I’m not really doing my job. I need to make sure that all kids eat.”

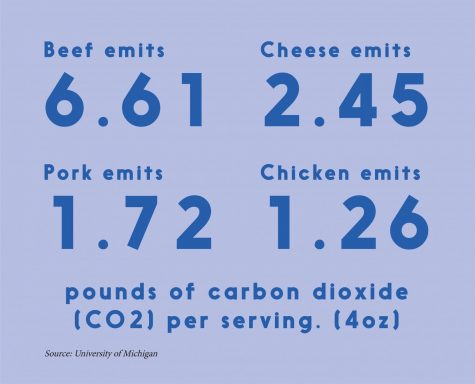

Out of all the foods consumed in the United States, beef has the second largest carbon footprint, emitting 6.61 pounds of carbon dioxide (CO2) per serving. According to Demory, beef is served 13-15 times in a six-week period throughout the 27 schools in the district. Last year, the district used 31,278 pounds of beef, meaning the ICCSD was responsible for over 500,000 pounds of CO2 emissions.

The issue is much deeper than whether the ICCSD has the financial capacity to replace meat with other alternatives, like tofu. The real barrier to executing a change this drastic is the federal government. Because the menu must comply with guidelines set by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), eliminating or reducing meat options is difficult.

“The very first thing we have to do is make sure that we meet our federal guidance because if we don’t, we’re not following our rules,” said Demory.

When the controversial Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act was implemented in 2010, school lunches saw something akin to a makeover. The food pyramid was replaced with MyPlate, a plate with recommended serving sizes for each food group. The importance of consuming fruits and vegetables rose, as did the protein intake. For school lunches, protein sources are most commonly presented in the form of meat.

For many students, the change may have gone unnoticed if not for the sudden absence of chocolate milk or the increase in mandatory vegetables. For school administrators, this marked a shift from local to national control over school lunches.

Despite strict restrictions regarding protein sources, Demory is optimistic that the current meal plan can still make a difference.

“In this kind of supersize-society that we have, it’s important that we teach kids what a portion size should look like, for health, but also for the footprint that we leave,” she said.

For Demory, it’s all about educating the next generation on how to consume consciously. While many schools around the country protested the Hunger-Free Kids Act upon its implementation, Demory took it as an opportunity to make lunch menus the best they could be.

“Unfortunately, the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act was an initiative of Michelle Obama. I say ‘unfortunately’ because it became a political piece,” she said. “It shouldn’t be political. How can you find fault with serving fruits and veggies to kids?”

One way that students at West have been trying to combat the negative effects of beef consumption by changing their diet. One of these students is Annelies Knight ’21. She has been a pescatarian for over a year,meaning she eats fish, but not other meat.

“Before, I really didn’t eat that much meat,” Knight said. “And if I did, it was locally sourced, just because I wanted to support local farmers.”

From potato chips and cookies to salads and pre-wrapped sandwiches, West appears to have a wide range of food options available for students during lunch. However, beneath the surface, a surplus of beef products can make it difficult for students like Knight to find options at West.

“They do serve a lot of meat to the point where it’s hard to find even pescatarian options,” Knight said. “A lot of the pre-made sandwiches and stuff don’t have options without meat in them.”

For the past three years, Abbie Callahan ’20 has been vegan, meaning she consumes no animal products. Originally, she made the switch due to the empathy she felt for animals, but she soon recognized the positive environmental and health impacts of an animal product-free diet.

“If we don’t make a conscious effort to change in a positive way, our world will continue to change in a negative way. There’s no denying that,” Callahan said. “There’s going to be a point where it’s irreversible.”

Another concern facing West is the waste that comes from meals, something that the ICCSD has been trying to be conscious of in recent years.

“We are always mindful of packaging and plastic in our lunches,” Demory said. “We never use styrofoam. On our recent disposable bid we included compostable and recyclable items so we have these items available.”

In addition to limiting packaging, the school district donates some of the excess food to organizations such as the Salvation Army or Table to Table.

“We try hard to not overproduce, so we donate at the end of the week,” Demory said. “To again, reduce that footprint.”