Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Unsustainable.

Examining the actions the ICCSD and the Iowa City community are taking to combat climate change.

October 3, 2019

According to National Geographic, about 17% of the Amazon Rainforest has been destroyed in the last 50 years.

From a birds-eye view, the earth appears to be dead. What was once green is now brown; what was once frozen is now melted. Trees can no longer survive in the extreme temperatures, glaciers have completely melted and half of Florida is underwater. As uninhabitable as Earth may seem, you are still alive, and so are the 300 million refugees all around the world that have had to evacuate their homes due to rising sea levels. This is no dystopian world. According to NASA, this is our future.

Discussions around climate change have become increasingly tense in recent years. Some still deny its existence, while others argue that the effects of it will be irreversible in 18 months.

With all of this uncertainty comes an immense amount of debate. But the facts are indisputable. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Organization, animals are going extinct at an alarming rate and the US just faced its hottest summer yet.

As concerns over climate change rise, Iowa City and the school district have taken a number of measures to reduce their contribution to the issue, but many believe there is still more to be done.

Consequences of cows

In 2018, the ICCSD used 31,278 pounds of beef, which amounts to over 500,000 pounds of CO2 emissions. (Source: Alison Demory)

Blazing fires in the Amazon Rainforest are putting vast areas of unique ecosystems at risk, and some say this destruction is all because of cows. With the Amazon in flames, a question is being raised over whether cattle farmers are to blame. Afterall, it is no secret that farmers and ranchers have been burning down large sections of the Amazon for years to raise livestock. With methane levels soaring in recent years, many have questioned whether eating meat is worth the price of an increasingly warming world.

For the ICCSD, the answer to that question is yes. Alison Demory, Nutrition Services Director for the school district, is in charge of overseeing all aspects of the department, from meal production to recipe planning.

“I’m not sure at what point environmental reasons would ever become the sole decider of the menu,” Demory said. “I don’t anticipate that it would, quite frankly. Because if I don’t serve any kids, if [the majority don’t] want the plant-based options, then I’m not really doing my job. I need to make sure that all kids eat.”

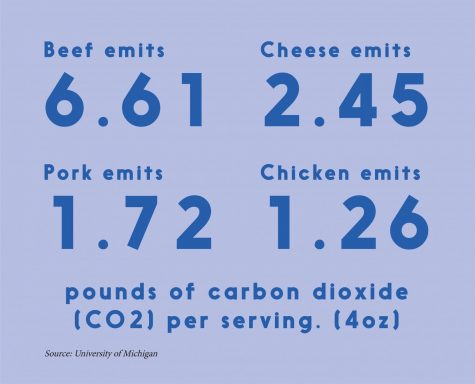

Out of all the foods consumed in the United States, beef has the second largest carbon footprint, emitting 6.61 pounds of carbon dioxide (CO2) per serving. According to Demory, beef is served 13-15 times in a six-week period throughout the 27 schools in the district. Last year, the district used 31,278 pounds of beef, meaning the ICCSD was responsible for over 500,000 pounds of CO2 emissions.

The issue is much deeper than whether the ICCSD has the financial capacity to replace meat with other alternatives, like tofu. The real barrier to executing a change this drastic is the federal government. Because the menu must comply with guidelines set by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), eliminating or reducing meat options is difficult.

“The very first thing we have to do is make sure that we meet our federal guidance because if we don’t, we’re not following our rules,” said Demory.

When the controversial Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act was implemented in 2010, school lunches saw something akin to a makeover. The food pyramid was replaced with MyPlate, a plate with recommended serving sizes for each food group. The importance of consuming fruits and vegetables rose, as did the protein intake. For school lunches, protein sources are most commonly presented in the form of meat.

For many students, the change may have gone unnoticed if not for the sudden absence of chocolate milk or the increase in mandatory vegetables. For school administrators, this marked a shift from local to national control over school lunches.

Despite strict restrictions regarding protein sources, Demory is optimistic that the current meal plan can still make a difference.

“In this kind of supersize-society that we have, it’s important that we teach kids what a portion size should look like, for health, but also for the footprint that we leave,” she said.

For Demory, it’s all about educating the next generation on how to consume consciously. While many schools around the country protested the Hunger-Free Kids Act upon its implementation, Demory took it as an opportunity to make lunch menus the best they could be.

“Unfortunately, the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act was an initiative of Michelle Obama. I say ‘unfortunately’ because it became a political piece,” she said. “It shouldn’t be political. How can you find fault with serving fruits and veggies to kids?”

One way that students at West have been trying to combat the negative effects of beef consumption by changing their diet. One of these students is Annelies Knight ’21. She has been a pescatarian for over a year,meaning she eats fish, but not other meat.

“Before, I really didn’t eat that much meat,” Knight said. “And if I did, it was locally sourced, just because I wanted to support local farmers.”

From potato chips and cookies to salads and pre-wrapped sandwiches, West appears to have a wide range of food options available for students during lunch. However, beneath the surface, a surplus of beef products can make it difficult for students like Knight to find options at West.

“They do serve a lot of meat to the point where it’s hard to find even pescatarian options,” Knight said. “A lot of the pre-made sandwiches and stuff don’t have options without meat in them.”

For the past three years, Abbie Callahan ’20 has been vegan, meaning she consumes no animal products. Originally, she made the switch due to the empathy she felt for animals, but she soon recognized the positive environmental and health impacts of an animal product-free diet.

“If we don’t make a conscious effort to change in a positive way, our world will continue to change in a negative way. There’s no denying that,” Callahan said. “There’s going to be a point where it’s irreversible.”

Another concern facing West is the waste that comes from meals, something that the ICCSD has been trying to be conscious of in recent years.

“We are always mindful of packaging and plastic in our lunches,” Demory said. “We never use styrofoam. On our recent disposable bid we included compostable and recyclable items so we have these items available.”

In addition to limiting packaging, the school district donates some of the excess food to organizations such as the Salvation Army or Table to Table.

“We try hard to not overproduce, so we donate at the end of the week,” Demory said. “To again, reduce that footprint.”

A climate crisis

A single vehicle emits about 4.6 metric tons on average per year, according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

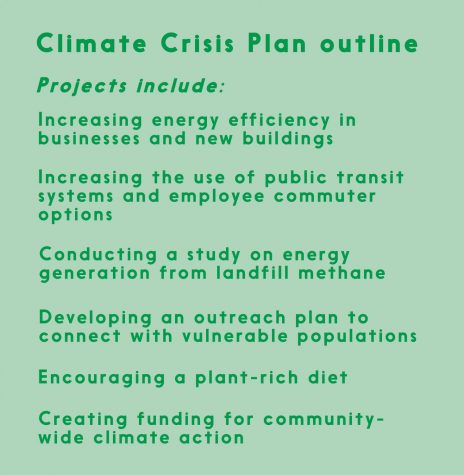

The Iowa City City Council voted to declare a climate crisis on Aug. 6. The council has challenged the city to curb the effects of climate change by adopting a strict plan consisting of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 45% by 2030 and attempting to get to net zero emissions by 2050.

“We want to play our role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions enough to avoid serious, long- term damage to human life or other life on Earth. That’s the big picture,” said Iowa City mayor Jim Throgmorton.

Though the plan may sound simplistic, Throgmorton knows that the issue requires a more complex solution.

“I think a key step is not to simply rely on math, saying, ‘Okay, in order to achieve our goal, we need a 45% reduction,’” Throgmorton said. “Instead, [we need] to ask the diverse public what matters most to them.”

According to Throgmorton, the answer to this question lies in finances. Since the most effective ways to combat the climate crisis involve expensive investments like the installation of solar panels or better heating and cooling systems, the city is trying to find avenues to financially incentivize people in a way that benefits both the environment and their incomes.

“Some people might worry about the affordability of housing, which in part is directly related to the cost of utilities, like getting gas for heating, electricity, better conditions and so on,” Throgmorton said. “People might be very interested in reducing the amount of money they’re spending on utilities.”

One significant step that Iowa City is taking towards achieving their goals is the formation of a new Climate Action Coalition. The group will focus on advising citizens about what steps can be taken to combat climate change, as well as trying to get the public engaged in the plan.

“I think it’s really important not to rivet your attention on how bad things can be, but to instead focus on the opportunities created by the need to avoid those damages,” Throgmorton said. “If we face a climate crisis, we should respond as if it were a crisis.”

Another route the city is taking to become more sustainable involves transportation. With the implementation of a bike share in the next year, Iowa City is working towards fulfilling the climate action plan that called for shifting 55% of transportation to sustainable options.

Transportation Director Darian Nagle-Gamm headed this partnership with Gotcha Mobility, a transportation company. The bike share program will provide electric-assisted bikes located at convenient locations throughout downtown area.

While this new addition could incentivize people to choose more sustainable options and provide them with easier access to them, the bike share program alone will not have the capacity to eliminate all emissions due to the inevitable use of cars.

4.6 metric tons is the average amount of CO2 that a single vehicle emits each year as stated by the United States Environmental Protection Agency. At West High alone, 436 students have registered their vehicles for the school year. However, some of the West community opt to trade in their four wheels for two by eliminating the use of a car.

West science teacher Jeffery Conner initially began riding his bike to school because he didn’t own a car, but has continued to bike instead in an effort to become more environmentally-conscious.

“I’ve now been teaching for seven years, and I could get myself a car, but I have chosen not to,” Conner said. “I think that it’s good to have the exercise and it’s good to help the planet.”

Conner rides his bike year-round, from 90 degree heat to snow storms. Even when the weather is too dangerous to bike in, he utilizes public transportation all in an effort to reduce his carbon footprint as much as possible.

“I have a feeling that things are going to get a bit harder in the future as a result of climate change. I want to look back and know that I made choices that didn’t affect things as negatively as what some people did,” Conner said. “I know, though, that regardless of the fact that I bike, I’m still contributing to the climate change problem. The way that all of us live, our lives are not sustainable.”

Homegrown

For many, 2012 proved to be a massive breakthrough in the grocery shopping world as the bulk-buying, super-sized Costco warehouse made its way to Coralville. But for local and organic shoppers, the arrival was a nightmare.

Stores like Costco that source from all over the world contribute to a massive carbon footprint. Like many businesses, most large corporations are owned by shareholders. Since shareholders generally don’t all live in one area, money produced by Costco does not return to one singular community.

For this reason, Erin McCuskey, the customer service lead at New Pioneer Food Co-op, believes that shopping at stores which provide locally-produced products is crucial to invest in community businesses.

“I realized a long time ago that protecting the food shed is a really important part of our mission,” said McCuskey. “Protecting the food shed means providing a store so people can sell their local goods.”

New Pioneer has played an active role in the Iowa City area for over 40 years, providing a place where people can buy locally sourced products. A common misbelief is that organic products are superior to local ones, resulting in many people disregarding products unless they possess the highly coveted “Certified Organic” label.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, becoming a certified organic producer is a process that typically takes at least three years and thousands of dollars—something that is not always feasible for small farmers.

“It is more important to be a marketplace for local goods over a marketplace for organic goods,” said McCuskey, noting that a lot of the products they sell are organic, even though they may not be certified.

“I think there are a lot of people around town who want to ensure that we can feed our families from some of the richest soil from west of the Nile,” said McCuskey. “And mostly, we’re using the soil for soda and gasoline and to send it somewhere else.”

With stores in the area offering comparable goods at a lesser price, consumers are faced with a dilemma: buy the cheaper products, or support the sustainability of the community. For those who choose to shop at stores like New Pioneer, they are making the decision to pay a price that reflects the fruits of its labor.

“Our pricing reflects the reality of what it costs to eat whole food,” said McCuskey. “It’s cool that you want to get your case of avocados at Costco for like, 99 cents apiece. I totally get it— I would want that too, myself. But that isn’t actually sustainable because avocados are farmed far away and [the low price] is being subsidized by poor labor practices.”

The Grinnell Heritage Farm, a small farm owned by Andrew Dunham and his family in Grinnell, Iowa, sells their products at New Pioneer and other locations in the area. From their perspective, factors like poor labor practices are detrimental for farmers like themselves who can’t compete with the low costs associated with unsustainable methods.

“One of the downsides to just looking at the checkout cost of food, like at Trader Joe’s or Costco, is that there’s so many external costs that are either subsidized by taxpayer money or pollution that is being emitted that is not being accounted for, or health effects that aren’t even being accounted for,” said Dunham.

In the end, the mission for the New Pioneer’s of the world is to support the community, but in a time where it has become all too easy to buy from businesses that source from all over the world, this has proven to be difficult.

“What’s important for the future of food production is on a state level perpetuating monetizing healthy soil, and then rewarding people for staying here and making food,” McCuskey said.

Avoiding commercial products at all costs is not a reality, but McCuskey still believes that people should be making as much of an effort as they can afford.

In this situation, the power is truly vested in the decisions community members make.

“You get to vote three times a day at least. So every time you spend money on something, you’re saying that you approve of everything that goes into that product,” Dunham said. “And so if you don’t want to have confinement hogs, then you have to stop buying confinement hog products.”

Iowa City strikes back

In the midst of political turmoil over refusal to take action on climate change, over four million people held a strike, inspired by the voice of a 16-year-old girl. Greta Thunberg, Swedish climate activist, has taken the lead in organizing protests, gaining the attention she believes climate change deserves.

Joining 4,500 other locations around the world, Iowa City took part in this strike on September 20, with demonstrators marching out of their respective schools or jobs and meeting on the Pentacrest. The protest is a part of the global “Fridays for Future” where students combat inaction on climate change by leaving their school in protest.

For many, the high turnout is a reassurance. 76 year old Miriam Kashia from grannies for change has been dedicated to fighting climate change her whole life.

“There’s only so much a person can do, and I’ve done everything I can think of…so to [the young people] I say thank you. And we’ve got your back.”