Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

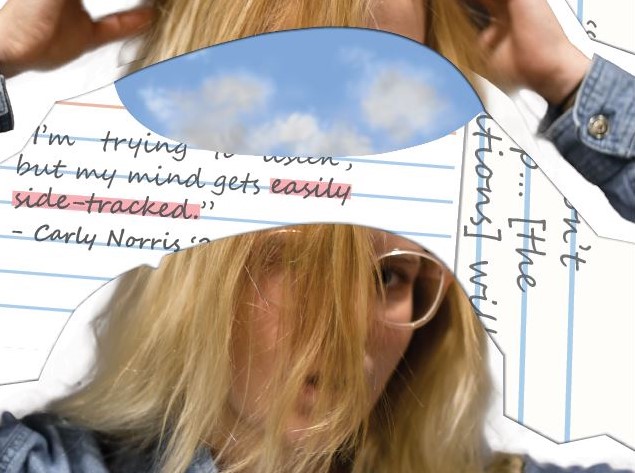

“I’m trying to listen, but my mind gets easily side-tracked.”-Carly Norris ’21

Out of sight, out of mind

From difficulty focusing to trouble writing things down, learning disabilities affect a large number of students at West.

November 17, 2019

The soft glow of the SMART Board beams at the front of the room, casting a low-lit shadow over the faces of those residing in the front row. As you are concentrating on the presentation in front of you, the disgraceful “ding” of an unsecured cell phone jolts you from your focus. As you attempt to return to your notes, the concerning “thud” of a hammer pounding away echoes throughout the courtyard. Now imagine if these inconveniences were paired with an added challenge: a learning disability.

Learning about learning disabilities

Carly Norris ’21 is among the nearly six million children in the U.S according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2016 survey data, who have been diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). She was diagnosed in third grade, a common age for children with this condition to be identified.

Although ADHD is not considered a learning disability, it can make the learning process for students more difficult, as it is characterized by the struggle to pay attention and the inability to control behavior.

According to Norris, focusing in school can be tough at times because she is easily distracted during class.

“It’s really hard when I’m writing essays, because I’ll be on one topic, and then suddenly I’m talking about a different topic and I don’t even know how I got there,” Norris said.

Holden Logan ’21 was diagnosed with ADHD and Dysgraphia at the age of six. Dysgraphia is a condition that causes a person to write illegibly with inconsistent spacing.

“I can’t write my own name without me not even being able to read it sometimes,” Logan said.

Although there is no “cure” for Dysgraphia, it can be supported through various accommodations such as 504 plans and Individual Education Programs (IEP) which provide students with a varying degree of assistance.

“I know one big thing is that teachers always complain about my handwriting,” Holden said. “So I will always ask them if I can take notes on the computer.”

Dyslexia is another common learning disability among students. According to the Dyslexia Center of Utah, it affects 20% of the U.S population.

This type of disorder affects the left hemisphere of the brain which processes language and can cause an individual to mix up letters or entire words while reading.

Jenna Alden ’23 was diagnosed with ADHD and Dyslexia in kindergarten which affects her experience in the classroom. According to Alden, although it can be a challenge to read fluently, that doesn’t stop her from learning.

“I couldn’t understand how to read but I could read to understand,” Alden said.

Gus Elwell ’22 has been diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) and ADHD both of which are conditions that share a significant characteristic: difficulty focusing.

“In your mind, you’re constantly jumping from one thing to another,” Elwell said.

Although both conditions are classified as neurological disorders, the symptoms of ADHD manifest themselves in a more physical manner, such as fidgeting or hyperactivity, than ADD. Elwell finds these things affecting him on a daily basis.

“A lot of the times, I will be having a normal conversation with someone, and I will just start talking about something completely different,” Elwell said.“It connects in my brain.”

Co-existing conditions

Norris also struggles with depression and anxiety, and although similar these conditions and other similar ones aren’t learning disorders, they often coexist with them.

Many learning disabilities are accompanied by “co-occurring conditions,” which take place when a disability triggers another disorder. For Norris, it can be difficult to manage these different conditions all together.

“If I’m having a bad case of ADHD, I don’t get anything done,” Norris said. “Then I have a lot of anxiety about not being able to get that done, which leads me into a state of depression where I don’t want to do anything because I feel like I’m a failure.”

Logan’s situation is similar to hers. While he has known he has ADHD and Dysgraphia since the age of six, he was only recently diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder and Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

“As high school has gone on, Dysgraphia and ADHD hasn’t become as much of a problem,” Holden said. “That switches the focus to the depression and anxiety which have also greatly affected my grades before, because they do greatly affect my ability to learn.”

According to one of Enrichment Learning Therapy’s Speech Language Pathologists Suzanne Moore, one learning disability can lead to the progression of another and can further amplify the stress a student is feeling.

“If you already have trouble understanding what you’re reading because you have a hard time with comprehension of language and you have a hard time looking at the letters and the word and decoding what that actually means, it’s just a huge snowball effect,” Moore said.

Labeled

“So many people have these issues and people don’t seem to want to talk about it.”

Katherine Yacopucci ’20 fears she is commonly seen as “overly talkative,” which is one of the symptoms of her ADHD. Oftentimes, this causes her to feel self-conscious.

“I don’t think people realize how many people have ADHD and how bad it can be,” Yacopucci said. “I literally don’t know how to stop talking, a lot of people just call me annoying and [I say] stuff like ‘guys I really don’t know how to stop talking’… it comes in so many different forms.”

According to Norris, there are also a multitude of misconceptions surrounding the condition.

“I feel like people have a lot of stereotypes about ADHD,” Norris said. “They think it’s that kid who’s fidgeting in class, looking all over the place, but sometimes it’s the person who’s staring at the board just trying to concentrate.”

Logan has also experienced individuals questioning his intelligence due to his Dysgraphia.

“I’m not stupid, I just can’t get my thoughts on paper,” Logan said. “I may be physically slow to write things down, [but] It’s not the fact that I’m stupid… it’s the fact that it just takes me a little longer.”

According to Logan, growing up in a conservative part of Montana, he was surrounded by a stigma on mental health. It was not until he moved to Iowa that he began to talk about it.

“The entire [mentality] was men don’t cry and men don’t talk about mental health and so I was very quiet about it for most of my life,” Logan said. “[Now] I’m all about just being open about it because it should be talked about more than it is.”

Yaccopucci agrees that raising awareness surrounding these conditions is a necessary solution to ending the stigma.

“If you don’t get help… [the conditions] will just keep decreasing how you feel about yourself.” said Yaccopucci.

Unseen struggles

Students with learning disabilities face a plethora of challenges throughout their early years of education. But in high school, another stressor is added to the list of things looming over them: college.

“In high school, it’s been a lot more difficult because you have to start balancing college preparation with the fact that these grades are going to follow you to college,” Yaccopucci said. “Your grades actually matter.”

The medication’s adjustment period can also be a cause of discomfort for students with these conditions.“You don’t start seeing results from your meds usually for these kinds of things for like a month,” Yacopucci said. “Which also makes it difficult because you’re experiencing new symptoms or new side effects while you are experiencing your anxiety and ADHD because your [medicine] isn’t working yet.”

According to Ewell, it can be increasingly hard to focus when off of his medication

“When I’m off my meds I get sick and really tired, or I get really energetic,” Ewell said. “But usually on my med’s I’m just… at a good place, not too tired, not too crazy.”

Another challenge is that language is unavoidable, especially in an academic atmosphere. According to Moore, this can take an emotional toll on students.

“Kids can really just shut down because everything about school [is] learning to read when you are in first, second, third grade. That’s the biggest goal,” Moore said. “Language is everywhere…By third grade we really start to expect kids to not only be able to read but be able to read to learn.”

Language is divided into two areas: what you can express linguistically, and what you can understand. According to Moore, the skill that is worked on the most at the high school level is reading comprehension.

“Our ability to read and our ability to understand spoken language is so intertwined that kids in high school, if they still have a language impairment, they’re going to have a really hard time,” Moore said. “Everything is going to be a challenge if you have a language impairment.”

Accommodations and accessibility

Students with learning challenges have multiple options for support, both formal and informal, that they can receive in the classroom.

For many, these accommodations come in the form of IEPs and 504 plans.

IEPs and 504 plans developed to ensure that a child who has a disability that is recognized under law has access to specialized instruction and other related services. Although they are created for similar purposes, the main difference is that students with 504s do not require specialized instruction.

While IEPs have funding and money tied to the program, 504 plans do not. This causes IEPs to have a higher level of requirement to be eligible for a special education.

Administrative consultant Steve Crew is responsible for ensuring that the districts are obeying the policies and procedures.

“They are required by law to make sure those students civil rights are not violated,” Crew said. “No matter how severe a students [needs] are, the district has to be able to provide those services.”

Some students, however, feel that these policies are not successful.

“In school, it’s been a little less helpful just because my teachers don’t seem to recognize the fact that I have them,” Yacopucci said. “I feel like they are very much ignored… and I know it’s really hard for a lot of kids to actually get them.”

All Iowa school’s are required to have a designated 504 plan coordinator to oversee that these accommodations are being met. For West High, Molly Abraham is in charge of this.

According to Abraham, it’s crucial that students talk to their guidance counselor if they feel as though their plan isn’t being followed.

“It unfortunately has to be a two way street. Once they leave this setting, it’ll be a one-way street, they’ll have to be the one to ask for them which is tough,” Abraham said. “So I guess in a way it’s getting them ready for that too.”

Once a student is diagnosed with a disability, the medical records are released to the school. Families are then given the opportunity to meet with Abraham to discuss a potential plan.

According to guidance counselor Greg Yoder, it’s imperative that the goals in the plan are attainable.

Once the plan has been agreed upon, it is then sent out to teachers on a trimester basis.

“If something’s not a realistic accommodation to be having in college we typically don’t try to implement that at the high school level,” Yoder said. “ We don’t want to set students up to fail down the road.”

Accommodations on standardized testing can also be an option for students with learning disabilities. Yacopucci found these were beneficial to her.

“Just extra time in general was such a relief,” Yacopucci said. “I felt like pressure lifted off my shoulders and I felt like I was able to concentrate and look at the questions more.”

Although the accommodations may be helpful, it can be challenging to receive the support from the accommodations that are needed.

“All of my other teachers expect me to bring them up, even though they are implemented by the school, and all the teachers have access to the fact that I have them,” Yaccopucci said. “It puts a lot of pressure on the student that already has issues.”

Norris echoes Yacopucci’s views on how difficult it is to approach teachers about her accommodations.

“Having anxiety, it’s really hard to make that leap to actually open up to a teacher,” Norris said. “It’s something very personal, and you don’ t always want to have that conversation… It kind of makes you feel like you’re less than them.”

Student Family Advocate Jamie Schneider emphasizes the importance of communication between teachers and students. By doing this, the student will be able to confirm their accommodation plan with their teachers. Her advice is to find a trusted adult to help facilitate the conversation.

“I 100% do not think it’s about staff or teachers not wanting to follow any type of plan, I think it’s just there’s a breakdown sometimes between the communication between the adults and the students,” Schneider said. “I really think that the students can do more in building those self-advocacy skills… grab an adult that you trust and feel comfortable with, and go talk to those teachers together.”