Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Surviving cancer: five years later

On September 29, 2015, WSS staffer Bess Frerichs’ mom Dannye Frerichs became a cancer survivor. Five years later, Bess shares her story.

September 29, 2020

When I was a kid, my house was full of music. My mom, Dannye Frerichs, was a singer. She sang in bands and at concerts, but what I remember most is hearing her sing at home. She would sing while getting lunch ready, while cleaning, while I was playing with my older brother Rob Frerichs ’19 and my twin sister Rosalynn Frerichs ’21. These were the moments that defined my childhood.

“When I think of my childhood that’s the thing I think of, playing music and singing and listening to mom,” Rosalynn said. “We’re just a very musical family, we always listen to music during car trips, [and] we watch musicals together.”

Once we turned eight, we picked up our own instruments. My brother picked up the violin, my sister chose the flute and I started on piano before switching to the harp. When we managed to pick up the basics of the instruments, we would play pieces together and my mom would sing.

I never really thought anything about that would change. Until the summer of 2015, when Dannye got diagnosed with oral cancer.

Cancer Summer

“At some point, I bit my tongue and it didn’t heal,” Dannye said. “I didn’t really think anything weird about it, but I went to [River City Dental Care] … And they’re like ‘The funny thing is, if I didn’t know better’—because I was 37 and vegetarian and I ran most days and I was pretty healthy—’if I didn’t know better I would think that this was cancer.’”

Just to be safe, Dannye made an appointment with Oral Surgery Associates of Iowa City to get a biopsy on Oct 2, 2014. The results came back negative. Concerns alleviated, and with the sore gone from surgery, it was written off as a strange injury.

Except the sore came back during the summer of 2015. Dannye went to the dentist again, who told her to get another biopsy. It barely even crossed her mind that it might be cancer this time.

“The first time we were all worried about it,” said my dad, Aaron Frerichs. “And then the second time, when the first one had come back negative, we weren’t even really concerned.”

Dannye ran an in-home daycare from 2013 to the summer of 2020, and she had just put the kids down for a nap on June 24, 2015, when she got a phone call from Dr. Chad Pfohl, her surgeon at Oral Surgery Associates.

“Dr. Pfohl called me and I didn’t realize why at first,” Dannye explained. “I started saying that I was feeling much better, and then it dawned on me that they had already called me on Monday to see how I was. It’s funny, last time I was so freaked about it, and this time I didn’t even give it a second thought. And I said, ‘You had a bad result didn’t you?’ He said yes, and that they wanted to see me immediately.”

She called Aaron and had him come home from work. Only a few hours later, Dannye met with an oral surgeon.

“We went to the oral surgeon and he said he was so sorry for us, he said it was really unlucky and it was so funny we both laughed,” Dannye said. “It hadn’t set in yet for Aaron and me I don’t think. We just talked about whatever.”

The doctor explained that she had a tumor growing on her tongue and that the margins of the sample were still active, meaning they hadn’t gotten it all. He had already made her an appointment with otolaryngology—treatment of the ear, nose and throat—that following Monday.

“I think he said something along the lines of, ‘this will consume the rest of your year’ and we didn’t really believe him then,” Aaron said.

My parents came home from the appointment and told Rosalynn, Rob and me that Dannye had cancer. My sister and I were 12 and my brother was 14 at the time, so when they told us not to worry, I didn’t. They told us they had caught it early, and that Dannye wasn’t in any danger.

“It wasn’t life-threatening, so I never really worried,” Rosalynn said. “I remember [my therapist] asking me, ‘Oh wow, that must have been scary,’ and I was like, ‘No.’ Because there was never really anything that was like, ‘Oh my God, it’s the end of the world.’”

Along with telling us, Dannye also told our family, and then eventually posted the news on Facebook.

Aaron and Dannye went to the otolaryngology appointment a few days later. During the appointment, they found that the tumor was at stage two. For oral cancer, this means that the tumor was between two and four centimeters large and had not spread yet. Preparing for surgery and treatment involved getting a tumor board of specialized doctors to go over possible treatment plans. Dannye also had to see radiation, anesthesiology, and a speech pathologist to find out what would happen to her voice. The surgery to remove the rest of the tumor was scheduled for two to three weeks later.

The day before surgery, we went out to eat at Trumpet Blossom, and—since surgery would make it impossible for her to sing for a while—Dannye sang Serenade in Blue at the restaurant.

Dannye’s parents and brother came to visit the day of surgery, and her brother, Mike Seager, decorated the hospital room that she would recover in. Her parents had driven down from Cedar Falls, and Seager was lucky enough to be in the area for RAGBRAI.

July 17, 2015, was surgery day. I don’t remember what I was doing on the day of surgery, but Rosalynn had her last day of College for Kids and Aaron went with her.

“I didn’t want them to miss that,” Dannye said. “And I was just going to be in surgery, he’d be back by the time I woke up. And so I told him to go and he was a little unsure about it but I was like, ‘No, go. We’re not losing this too.’”

Dannye kept a very positive attitude about the whole situation. She even startled her surgeons by being so upbeat about it.

“I walked in and was like, ‘Hi, I’m Dannye, I’ll be your patient today’ and they were all like, ‘What.’ … I also told them a joke because I heard it was good luck,” Dannye said.

The surgery went smoothly, they took about a third of Dannye’s tongue, her lymph node in the left side of her neck and the lymph node underneath her chin. None of the lymph nodes were cancerous, but they took them as a precaution anyway. They performed the surgery through the neck but were even able to hide the scar in the natural folds of the neck. She lost feeling around a large portion of the neck, her tongue and part of her jaw. They had ended up having to move a nerve in her face so her smile was lopsided for months after.

“I was so happy: no reconstruction, no skin graft, no feeding tube, no trache[ostomy],” Dannye said. A tracheostomy opens up a hole into the front of the neck to create a direct airway to help with breathing. “A trache I was really really worried about because I thought they’d damage my throat. In fact, I asked them to be as careful as possible with a breathing tube during surgery and they said they’d use a smaller one if they could.”

Later that day, we visited Dannye in the hospital. She had drains in her neck and her tongue was swollen, but she was able to talk to us. Because Dannye was a lot younger than most oral cancer patients, a lot of what the doctors told us to expect ended up being different. Being able to talk right away was just the beginning of the differences.

“I remember visiting her in the hospital,” Rosalynn said. “That wasn’t a lot of fun. But it wasn’t horrible, I wasn’t grossed out or anything.”

Dannye stayed in the hospital for three days, and then things went back to normal. We went camping with our grandparents and the only thing that was different was that Dannye had to be extra careful about sunburns. About a month after surgery, she started radiation therapy.

Radiation Fall

Since the tumor was completely removed with surgery, the radiation was purely a preventive measure to stop it from coming back. Dannye had hoped this meant she wouldn’t have to go through radiation, but she wasn’t that lucky. There had been a study recently that showed that young females with oral cancer often had a very aggressive form of it and it was determined that the safest option was to go through with radiation.

The problem with the radiation was that it was highly unlikely that Dannye would ever be able to sing again. Dannye knew pretty early on that radiation would destroy her voice, which is why she had wanted to avoid it.

“We just hoped for the best, I figured it was probably going to be gone but I was so determined,” Dannye said.

Photon beam radiation therapy, the type of radiation therapy that Dannye received, is a type of external radiation. It uses photon beams to destroy the cells in the targeted area. Unfortunately, it kills all of the cells, including the healthy ones.

“The idea of radiation treatment is to kill everything and assume the healthy stuff will come back. It sounds barbaric but I’m just glad we have this option,” Dannye said. “It’s better to be sick from cancer treatment than to be sick from cancer.”

Radiation therapy occurs in short repeated treatments over a length of time. Oftentimes, cancer patients have to live in an outpatient facility so they’re close enough to the hospital for treatment. Luckily, we lived close enough to the hospital that Dannye could go in every morning for her appointments. Dannye had radiation therapy on weekday mornings from Aug. 18 to Sept. 28. Each appointment lasted 10 minutes and cost $3,000.

Luckily, our insurance covered most of the cost. Aaron had set up the health savings account so that we had a high deductible of around $5,000. But once we reached our deductible for that year, the insurance would pay the rest of it.

“During the couple of years when we were paying for the cancer treatment we hit our deductible almost immediately,” Aaron said. “I set it up so we had a nice buffer of 10 to 15 thousand dollars and as we went through that it obviously got depleted until we were basically down to zero at the end of cancer treatment. But that was sort of the plan.”

We also had a lot of support from friends, family and our church that helped out with appointments and food.

“I had to work throughout the whole thing,” Aaron said. “Work was really flexible, they gave me whatever time I needed, so I was able to go to any appointment that Dannye said, ‘Please come to this appointment with me.’ But otherwise, we were lucky because we had friends and family help out.”

During the radiation appointments, it’s imperative that you stay as still as possible, so the doctors tie your feet together, have you hold onto a bar, and mold a mask to your face that gets bolted down.

“It wasn’t claustrophobic at first,” Dannye said. “After wearing it I would get a snakeskin imprint on my face, especially after the swelling later on. But it wasn’t claustrophobic until the very end. Because it’s a nice room. They’ve got a pretend skylight where you can see and they give you a heated blanket. The problem is that they tie your feet together, and I remember telling the guy that if the zombie apocalypse was coming, he had to come in and untie me first.”

The effects of radiation are delayed by about two weeks after treatment starts. So after the first nine treatments, the symptoms started appearing. Dannye described the symptoms as a bad head cold. She had trouble swallowing, soreness in the mouth, and fatigue. Her salivary glands were starting to fail, and not long after, her taste buds stopped working. The symptoms continued to get worse, and she was put on medication to help with the pain.

Dannye was in speech pathology now, but most of the work was on the ability to swallow. The goal of speech pathology was to help Dannye relearn how to talk with damage to the throat and part of her tongue missing. They worked a lot on talking loudly without putting a strain on her voice and on talking out of vocal fry, or the lowest vocal register.

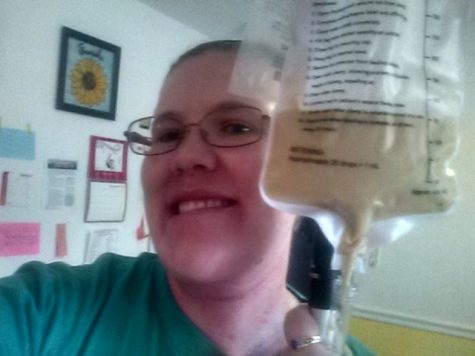

Tuesday, Sept 1, they had to put in a feeding tube. Dannye has an off and on dairy allergy so they had to find a formula for the feeding tube that was dairy-free. Except, there was a miscommunication between the nutritionist, social worker and Dannye herself mostly over the difference between a dairy allergy and lactose intolerance. Essentially, a dairy allergy is an allergy to all dairy products not just to dairy products with lactose in them.

The mix up led to Dannye being given the only dairy-free formula they had: infant formula. To add to the problem, she wasn’t being given any pain medication because the pain meds were on the second page of her meds list and were forgotten.

“[The doctors] were told to use just one can of infant formula and let it go through very slowly,” Dannye said. “But no one checked with the nutritionist and no one seemed bothered by the idea of giving a grown woman one can of infant formula very slowly.”

They got the switch up fixed by the next morning, but between Monday night and Wednesday morning, Dannye had received only 30 calories. She was also highly dehydrated but no one gave her an IV, and her lack of saliva made her very difficult to understand. They still didn’t give her any pain medication, but she was able to go home later that day and take her medication. The situation was eventually resolved through a series of emails between the nutritionist and Dannye, but the whole experience was very stressful.

Sept. 28 marked Dannye’s last day of radiation. At this point, her symptoms were terrible. Dannye had developed ulcers in her mouth, her throat and nose were filled with mucus, a half-circle of hair at the base of her head had fallen out and there were burns all along her neck and face.

Per tradition for finishing radiation treatment, Dannye got to ring the bell at the hospital three times.

“It felt good to be done with it, but there’s also the kind of, my treatments are done. I’m supposed to be better but I’m not yet. And it got worse for a bit. And I wanted to be able to sing again,” Dannye said.

Recovery Winter

With radiation completed, the only thing left was to slowly recover. However, because symptoms of radiation take about two weeks to show up, the two weeks after radiation ends are always the worst. And with no end goal in sight, recovery is very difficult for your mental health.

“I’m not in the best of spirits because I don’t know how much longer this will take,” Dannye wrote in a Facebook post shortly after radiation finished. “It’s so hard to get up every morning and realize that you’re feeling worse than the day before. You keep pinning your hopes on the next day to be the turnaround day and it’s so depressing when it’s not.”

It was easy to underestimate how long and difficult recovery was going to be. Dannye still couldn’t swallow and they continued to increase the pain medication for weeks after radiation ended. The hurdles that Dannye needed to get over seemed almost impossible to clear at that point.

“Big bumps in the road include learning to eat, hoping my taste buds return, hoping my singing voice returns. Getting back to being able to stay awake all day and chase toddlers for a living seems impossible right now,” Dannye wrote.

Eventually, they were able to turn the meds around and start to decrease the doses, but that just led to more problems in the form of withdrawal.

“I’m six weeks post-radiation and in active recovery still,” Dannye wrote in her log in November. “I’m having a hard time with pain and mood swings, trying to work out withdrawal symptoms on the narcotics.”

Her mental health got bad enough that Dannye went to see her psychiatrist. She tried therapy at first but eventually decided on another medication. She was hesitant to add another medication onto the list that she was trying to step down from, but her depressive episodes were too bad to do nothing.

“I just imagined what my mother [who had worked in hospice] would say at the time and she was like, ‘Yeah, I know you’re worried about another med but this one’s very mild and you have to get through now and worry about that later,’” Dannye said.

Along with psychiatric medication, Dannye also did some basic therapy mental exercises to stay positive. And, to lift her mood, Aaron planned a trip to Disneyworld in April.

“I was feeling bad about how exhausted Aaron was, and he was feeling bad about everything I was going through so much that I got a surprise a few days ago,” Dannye wrote in her log. “He brought me something and asked if there was anything else he could do for me. And I joked that he could take us to Disney and he says, ‘Well, I’ve been looking at flights.’”

“It was basically, we’re going to go on vacation when you get better,” Aaron said. “And Dannye loves Disney and so we decided to go to Disney World. Could we afford it? Maybe not, but whatever, it’s fine.”

It was slow going, but Dannye continued to pass different milestones. In November, she was able to sleep lying down and still be able to breathe, she was able to taste the salt in her mouthwash, and she was able to go a night without pain medication.

The end of November and December were the worst mentally because Dannye was fully walking down from the drugs.

“On my good days I can work and clean the house and make dinner but not eat it,” Dannye wrote in her log. “And on my bad days, I cry a lot and sleep a lot and feel very useless and awful. I want to be done with cancer treatment. It would be worse if it was the kids but it seems like it’s everything else important: running, eating, my singing voice.”

But it continued to get better, Dannye had a PET scan that confirmed that she was still cancer-free. Because she was younger than most oral cancer patients, her teeth weren’t too damaged by the radiation and she was able to keep them all.

Over time, Dannye was able to start singing with her church choir, although she was quiet and her voice had deepened from the radiation. As her voice slowly got back to normal, she would start to sing slightly higher voice parts. She also started piano lessons so that she could keep playing music even if she wouldn’t be able to sing anymore.

Her doctors started the process of taking her off the feeding tube in January. Dannye was very excited to finally get to eat normally again.

“I would have given my left arm for a glass of water in the middle of treatment. I remember you get to fill [a glass of water] up and you get to hold it and it gets your fingers wet. And then you put it all into the tube, and not a drop of it goes down the back of your throat where it feels like you’re on fire,” Dannye said.

To make sure that she could eat enough without the tube, they had her stop using it for a week or two, and if she was able to maintain her weight without it, they would take the feeding tube out. Dannye lost a little bit of weight in the time span, but it was small enough that they removed the tube anyways.

“[The] policy is to have the same surgeon place and remove the tube, apparently other surgeons are reluctant to work on someone else’s patient, but my surgeon wasn’t coming to the clinic anymore so it had to be someone else,” Dannye said. “They had to really search to find someone willing to do it and they said it was going to hurt more because of that … I had to wait 45 minutes for a doctor and when he walks in he says, ‘This will be painful and traumatic.’”

It wasn’t pleasant, but once her feeding tube was out and the hole had closed, Dannye was able to swim, run and sleep on her side or stomach again.

By February, Dannye was completely off the medications and she switched speech pathology for a voice teacher to help her voice.

New Normal

At this point, life was as back to normal as possible. In cancer terms, the period after treatment and recovery is referred to as the “new normal.” There were small every day adjustments in our lives that would never change.

The radiation therapy had damaged Dannye’s salivary glands to the point that they barely worked at all. She had to start carrying around water wherever she went. If Dannye went too long without drinking water, her mouth would dry out and become uncomfortable. Also, she couldn’t eat dry foods, and any food she did eat needed the help of water to swallow. We quickly got used to water bottles being spread out all over our house.

“We have a chair in our kitchen specifically dedicated to hold her water so that if it gets knocked over it doesn’t spill onto any computers,” Rosalynn said. “We keep water in jugs too in case the water ever gets shut off.”

Her taste buds have cycled through different stages of accurateness. Sometimes food tastes exactly as it should. Sometimes, it’s completely blank. Sweet things, like fruit, tend to taste extremely bitter to her. On rare occasions, foods would taste like something completely different. Once, zucchini tasted like buttered popcorn to her. Another time, a banana peanut butter smoothie tasted like butterscotch.

“My taste buds have gone up and down, backward and forwards and God only knows,” Dannye said. “[The doctors] were like, ‘They shouldn’t change at all after 18 months,’ and I was like, ‘Well you tell them then because they don’t listen to me.’”

Dannye having had cancer is just another part of our life, so much so that my whole family makes jokes about it.

“It doesn’t freak out all of our friends, but it does freak out some of them,” Rosalynn said. We’re like, ‘It’s fine, like our mom makes jokes about it.’ We’ve always been a family that makes fun of each other and that translates to cancer as well.”

By August 2016, Dannye had fully regained her voice. Her speaking voice was lower than it used to be, and that wouldn’t end up changing, but the lower register meant her range was actually larger than before. She could now sing a half octave lower than she used to be able to.

“I used to sing both parts of the duets from Oklahoma and Phantom of the Opera,” Dannye said. “I performed it that way a couple of times. I’d sing her part in her octave and then his part in his octave.”

She was able to perform duets with my siblings and me again, and she started singing at the Hope Lodge in Iowa City, where cancer patients who live too far away are able to live while they receive treatment. Dannye had done music therapy there in 2013, but now she got to share her cancer story with others who were going through the same thing.

About a year after she got her voice back, the new lower register of her extended range started to go.

“That didn’t last long,” Dannye said. “And my upper range was also shrinking, but I was trying to ignore it. I rewrote music into a lower key and pretended I didn’t know why I was doing it.”

It wasn’t until the summer of 2019 that her voice really started to go. It became painful for her to sing at all, and even talking for a long period of time hurt. We knew that radiation damage continuously gets worse the longer away from treatment you get, but we didn’t really realize what that would mean for her voice.

She was still able to sing for her friend and music partner David Evans, who would play accompaniment on the piano. He was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2013 and lost the ability to play in May of 2016, but Dannye continued to sing for him at Legacy Senior Living Dementia Care. My siblings and I would also cart our instruments in every once and a while and play. Evans was able to recognize Dannye through her singing for a while, even as his memory degraded. He passed away on Aug. 23, 2019.

“David’s health went down, and I was able to sing for him,” Dannye said. “But by the time of his funeral, I had pretty much lost my voice. … I can’t get my head around it. I don’t know what to do without [my voice]. I’m glad I had it for David, but I miss it. It hurts to talk.”

Dannye had a throat study done to figure out why she was losing her voice. They stuck a camera down her throat to observe the vocal folds and found that her vocal folds—which after cancer treatment had been unaffected—had deteriorated. Progressive radiation damage had spread down her throat and harmed her esophageal sphincter, a stopper in your throat that opens and closes to let food into your stomach, but stops stomach acid from coming back up and damaging your esophagus. Due to radiation, the sphincter could no longer close all the way and stomach acid was coming back up and injuring her vocal folds.

She’s had time to get used to not being able to sing again, but it’s still difficult. Dannye has been five years cancer-free since Sept. 29, 2020, and she had her voice for about three of those years.

“At this point, I don’t really sing. I try, but I know I can’t project over the piano anymore,” Dannye said. “I need to figure out if it’s bad to push through when it hurts because I went to Hope Lodge for a little while and just pushed through it. I kept thinking I had a cold but the next day my throat would be swollen and I would feel drainage in the back of it … And so the question is should I sing when it hurts or not because technically I can. I don’t know if it’s just going to hurt and it’s fine or if I’m actually making it worse.”

While it’s disheartening to know that the effects of radiation will continue to get worse for the rest of her life, Dannye tries to stay optimistic about it. The cancer was caught early enough that the trouble wasn’t with getting rid of the cancer but making sure it doesn’t come back, we were able to pay for cancer treatment and she got her voice back after cancer, even if it wasn’t forever. We all miss her voice, but we’re extremely grateful that she’s healthy.

“It’s not just me,” Dannye said. “This happens to people, they lose something that they love so dearly, and you just have to accept it and move on.”

krissie Chase • Sep 29, 2020 at 7:31 pm

A truly sweet and tender story showing bravery and true grit from the entire family

Hang in there sweet lady