Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Unmuted

Examining the local evolution of Black Lives Matter amidst a global pandemic.

October 19, 2020

The streets of Iowa City were lined with protesters demanding racial equality. Groups chanting “Hands up, don’t shoot” and “Say their names” filled every corner of the city while voices echoed across graffiti-lined streets. Megaphones boomed over the crowd as organizers shared their experiences, and the stories lingered in the ears of those who listened.

Many Iowans attended the local protests motivated by recent instances of police brutality against Black Americans this summer. According to the New York Times, 15 million to 26 million people in the U.S. alone have attended rallies in support of the Black Lives Matter movement since the killing of George Floyd in May. These numbers represent the greatest turnout for a movement in the history of the U.S.

Pre-existing pandemic

Systemic racism refers to the structures in society that place many people of color at a disadvantage in various aspects of life. According to USA Today, effects are shown through “success indicators,” including unemployment rates, income and education. COVID-19 has exacerbated the systemic inequalities that the Black population already faces which leaves them especially vulnerable to the pandemic.

According to the CDC, COVID-19 hospitalization and infection rates are significantly higher for Black Americans than their white counterparts, at 2.6 and 4.7 times, respectively.

“We already knew that African Americans fare worse in terms of the number of health outcomes,” said Jessica Paige, University of Iowa Sociology and African American Studies Professor. “But now, in addition to that … countless faces of African Americans have passed away, and it’s like taking these health disparities and enhancing them and making them visible for everybody.”

Because COVID-19 has also left millions unemployed, countless individuals are forced to decide between paying this month’s rent or putting food on the table. It has been difficult for many to stay afloat, but marginalized communities have been hit the hardest by these economic effects.

“I think all these things, these moments of unrest, are never about one thing, and they never arise suddenly,” Paige said. “This has been happening, and I think the pain has been so significant from the pandemic that it’s just making people even more frustrated, frightened and in some cases, desperate.”

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the national unemployment rate in August was 8.4% but was significantly higher for Black Americans at 13%. Similarly, the median net worth of a Black household is $17,700 compared to $171,000 for white families, as reported by The Guardian. These economic factors can already be limiting, but Paige feels the pandemic has only heightened their influence.

“There are people who have lost multiple family members, who are not working, who don’t know how they are going to pay their rent,” Paige said. “Then you add in the police brutality piece [and] you have this visual once again of the ways in which the United States has abused and killed Black people.”

Due to these disparities, Angie Jordan, the director of the South District Neighborhood Association, is working to promote equity within the area. She is facilitating multiple programs, one being the “Neighborhood Nest” which aims to provide childcare and a safe learning environment for children of working parents.

“The intent is to serve directly [to] the folks who don’t have child care and supervision,” Jordan said.

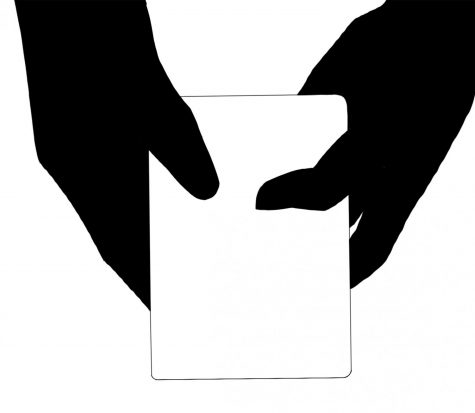

Other programs include voter drives, affordable housing initiatives and most recently, a forum to empower Black female business owners in the area.

Tasha Lard, a member of this group, is now the owner of JD’s Beauty Supply. According to Lard, the process of opening up her business was strenuous as multiple instances of racial profiling made it difficult for her to obtain a lease.

“I thought once I had funding, I had my money in order, I had vendors all lined up that everything else would be easy,” Lard said. “The problem came when [I had] to find the actual location.”

Once the lease was lined up at the first location Lard found, all she had to do was sign it. However, once she saw the terms of agreement in writing, she ultimately decided against signing the lease.

“[It] was so stereotypical that I was just like ‘Oh my god.’ I literally cried because it said … you can’t do any advertising. You cannot play loud music in the [store]. You can’t have people standing around,” Lard said. “At that point I knew they had stereotyped me.”

Lard continued the search for a location, this time settling upon a property that had been vacant for over a year. She called the realtor, and after multiple disregarded phone calls, she decided to leave him a voicemail.

“Once I left a voicemail, you can tell that I’m an African American woman, and he did not call me back,” Lard said. “It didn’t feel right, so I had a couple of my white friends call, and he called them back. He had the conversation on what they wanted the space to be, how much they wanted to lease it for, everything. He even called them back multiple times, but to this day, he has not yet called me back, not once.”

After numerous similar encounters, Lard eventually found and opened her store at 1067 Highway 6 E. in the South District. She aims for the business to be a service for people of color in the area.

“I got tired of having to go all the way to another state just to get those simple supplies for our hair because everybody’s hair texture is different,” Lard said. “So me opening in the middle of a pandemic—in the middle of Black Lives Matter—it was something that was needed for the community as a whole.”

Take it to the streets

Black Lives Matter is a progressive social movement founded in 2013 that garnered support in response to continuous racial profiling and violence against the Black community. It has grown over the years as individuals advocate for change through various methods such as donations, protests and contacting representatives. The movement gained unparalleled attention after the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor at the hands of police officers this spring.

Outraged by the deaths, a group of college students from the University of Iowa came together to protest in Minneapolis. After returning, the group began to organize rallies and soon became known as the Iowa Freedom Riders.

Ala Mohamed, a West High graduate and current University of Iowa senior, joined the IFR this summer. She is one of the organizers of the group and attended the first Minneapolis rally in March.

“It was a very scary experience. There were snipers on roofs, dogs and hoses, and it was a very big eye opener,” Mohamed said. “It just felt really upsetting that we were still going through it again with the protesting for equity.”

According to Mohamed, the response to protests in Iowa City has also been troublesome. Police officers have been monitoring protesters, stopping them after rallies, locating their routes and following them home.

“The founding of the police started off with slave patrol. If you have a bad base, how do you expect to have a [stable] house? You’re not going to get anywhere unless you deconstruct it and you start looking into other ways to fix the issues,” Mohamed said.

Sophia Lusala ’22, another IFR protester and City High student, shares these sentiments as she touches on the techniques used to seize people’s attention.

“We’ve tried to shut down the interstate multiple times, and when you try and do this, it costs the state money. Money talks. As soon as you start messing with their money, they’re going to start listening to you or they’ll retaliate. Either way, they’re going to start noticing you,” Lusala said. “Protesting is a way to get attention, but it’s also a way to come together and share with people what you feel [and] to let out your rage. It’s our right.”

Haleem Adams ’21 has been to all of the recent protests and adds that support is driving the movement as well.

“I feel excited … When I see a lot of people fighting for Black Lives Matter, I feel good energy,” Adams said. “I know that people are actually seeing the problem and [are] trying to make a difference.”

Fabio Rojas, sociology professor and social movement researcher at the University of Indiana, adds that an increased amount of free time created the perfect conditions for protest.

“The pandemic … creates a bunch of people who are at home, who are unemployed [or] underemployed; they don’t have stuff to do,” Rojas said.

Social media activist Liam Edberg ’22 agrees the pandemic has influenced people’s availability, adding that they are able to process information for a much deeper understanding today.

“People have so many things to do and so many commitments … when they were given the time, they found that they were able to advocate for stuff they always cared for. It made my emotions become very visceral, and I was feeling a lot more things than I was before, and I had time to sit with those thoughts,” Edberg said. “If everyone’s … wanting to express themselves … they found a really important way to do that.”

Revolutionary reshares

With over seven months of online interaction, it is no surprise that social media has become a powerful vessel for advocacy in the pandemic era. Generation Z has revolutionized activism in the digital world; informative posts regarding racial disparities, protest organizations, ways to help and more flood the feeds of many.

Himani Laroia ’23 recently became a strong advocate for the BLM movement and other social justice issues on Instagram. She was first inspired to utilize social media when she read an article about diverse ways to demonstrate support. She often reposts infographics and news posts regarding current events.

“I realized I cannot be a bystander of the problems I personally think are wrong,” Laroia said. “I must take action because I have resources at my fingertips to constantly educate myself.”

Due to his increased usage of social media during the pandemic, Edberg also found that it has become a vital platform to spread and share information.

“I think a lot of people just go on social media so that they don’t actually have to educate themselves and read the news, but if I can pepper a little stuff in there, I think including this aspect in daily life makes it more likely to reach people who wouldn’t go out of their way to find it,” Edberg said.

However, this hasn’t always been the case. In recent years, social media has garnered immense popularity as a platform for sharing widespread news about global issues.

“People become their own news outlets [and] their own reporters. So, things that previously might not have gotten a lot of coverage, not only get coverage now, but they get instant coverage,” Paige said. “It’s difficult for police or for other government figures just to say something didn’t happen or to create an alternate narrative. I think that’s really impacted people because there’s a place now to express concerns and to circulate information about ongoing inequalities.”

Instagram accounts such as @blackaticcsd have also played a role in the movement by anonymously shedding light on the experiences of students of color in the district. They aim to create a space for students to share their stories in hope of exposing issues they feel the school needs to solve.

Nadeen Mohammed ’21 believes the account is necessary as it draws attention to students’ experiences without exposing their identity.

“I think it’s a good way for students to tell their story without feeling uncomfortable because I can tell you the truth … I have talked to some teachers that have treated me differently … but they didn’t do anything about it,” Mohammed said.

According to Laroia, another reason to use the internet to advocate for BLM is because of the pandemic. She feels that since it is important for people to be social distancing, using social media is the safest way to spread awareness.

“I want to make sure people are safe, which is why online is a great outlet. You don’t have to physically go there and risk yourself [or] risk others at home. You can show your protest online,” Laroia said.

Although a National Bureau of Economic Research study suggests there is no evidence the protests have led to a spike in COVID-19 cases, many still see it as a cause for concern.

Vicki Carrica ’23 believes the protests are important to the movement and relatively safe, as long as people take proper measures to minimize the virus’ spread.

“If large groups of people aren’t wearing masks and are close together, however, it’s very likely that COVID-19 could get out of control and kill many more people,” Carrica said.

As mentioned in the New York Times, BLM protesters have worn masks at higher rates than those at anti-lockdown protests. Additionally, a group of professionals from around the country see systemic racism as a public health issue.

These health experts signed a letter that wrote, “Black people suffer from dramatic health disparities in life expectancy, maternal and infant mortality, chronic medical conditions, and outcomes from acute illnesses like myocardial infarction and sepsis. Biological determinants are insufficient to explain these disparities.”

Change in the community

The push for change has not gone unnoticed in Iowa City, with both the Iowa City City Council and ICCSD School Board making efforts to address the concerns of the public. At West, Interim Principal Mitch Gross believes that teachers must be actively anti-racist to be hired. To ensure that this is made a priority, he added the question “What does being an anti-racist mean to you?” on the job application forms.

“Black students matter, because when we look at the data, that hasn’t always been the case,” Gross said. “That’s a goal for all of us in education to make sure that those data points change and improve.”

Psychology teacher Amira Nash is working with an organization called Black Lives Matter at School-Iowa which strives to implement Black Student Unions districtwide. Nash is specifically organizing a BSU at West in order to create a community she wishes she had in high school.

“As a Black person in Iowa, you are almost always a minority in the majority of spaces you’re in,” Nash said. “I hope [BSU] is a safe space for us to learn more about our history together, to educate each other, to build community and to discuss our experiences … I hope it’s a space that promotes scholarship and self-esteem among our Black students and that it provides opportunities for our students to see positive representations of themselves.”

When Nash conducted the first BSU meeting on Sept. 15, over 20 students attended the virtual conference. According to Nash, they all brought a multitude of ideas and knew what they wanted BSU to be.

Mohammed, a member of the organization, said her friends complained to the administration last year about the lack of African American history curriculum at West. This, coupled with the BLM movement’s resurgence, inspired them to join the club.

“West doesn’t teach a lot about African American history. It does teach about the struggles, but it doesn’t include successes,” Mohammed said. “After BLM happened, we wanted to come all together and learn more about our history.”

This year, Nash will also launch the first ethnic studies class at West. The trimester elective will touch on a plethora of subjects ranging from identity, intersectionality and culture to privilege, oppression and empowerment.

“There are so many students that have been asking for this class and that want the opportunity for an in-depth exploration of contemporary cultural diversity,” Nash said. “Ethnic studies is the history of us, and all students deserve to see themselves reflected in the curriculum.”

At the district level, the school board is working to create initiatives that address equity problems and make schools more culturally aware.

Laura Gray is the director of diversity and cultural responsiveness at the district. This year, she manages the Cultural Proficiency Team which consists of 35 teachers. The group’s goal is to converse about topics such as implicit bias and privilege as well as strengthen skills like culturally responsive teaching. Her goal is to expand these trainings districtwide with the help of the teachers who have received instruction.

“Culturally responsive teaching is more than just about the social understanding of race and race relations,” Gray said. “It [also] takes [into account] what educators are doing academically. What are your actions? What’s the action happening within your curriculum?”

For Gray, the pandemic has magnified the issues in educational gaps for marginalized students not only through academic knowledge but also in support and contact. She emphasizes that emotional guidance and inclusivity should be at the forefront of people’s minds.

“[These disparities] already existed. We know that historically we’ve missed educating certain types of students,” Gray said. “We don’t have time to waste.”

School board member J.P. Claussen says that the group is working on the IFR’s demands, which include focusing all of their professional development efforts on cultural responsiveness, entirely reworking the student discipline handbook, hiring teachers and administrators of color and implementing an antiracist curriculum. According to Claussen, the three-year curriculum review process usually happens once every seven years. However, they are changing that process starting with social studies in hopes of having it done in a year.

“We’ve already identified some curriculum we want to use, including the book ‘Stamped.’ What we learned is that even though we have a great curriculum [in the works], all of our teachers aren’t ready to teach it,” Claussen said. “We’ve done some things in the past that were more harm done than good because it was presented in a way that was insensitive or offensive. We know we have to move quickly on this, but we also don’t want to move so quickly that we do more harm than good.”

The IFR is also concerned about the use of police in addressing conflicts at school.

“We don’t want cops escalating situations like that. You might get charged with something, you might get taken out of school,” Lusala said. “A lot of BIPOC students are scared of law enforcement … We have counselors for a reason, they are trained for these situations.”

Mariam Keita ’22 has seen these very moments with police officers throughout her time at West, and she agrees that they are unnecessary.

“When you have cops come in to break up student fights, it also has the tendency to say that those students are violent. Cops usually go through background training, and their training isn’t for kids … it’s for criminals and murderers,” Keita said. “Instead of giving the students help, you bring in a cop … it’s just not acceptable.”

Keita mentioned that on-duty police officers who get involved in student arguments are also required to carry guns while in school. Keita believes this instills fear in students which only causes more harm.

“Either the student is going to overreact because they’re scared of the police officer, or the police officer is going to overreact because they’re scared of the student,” Keita said. “They should just have correctional officers if anything gets serious. The most dangerous thing they should have is a taser or pepper spray.”

Claussen believes that principals should only call officers when a firearm is involved.

“We want the police involved if there’s real physical danger and safety issues. What we need to work on as a district … is messaging to our principals that that should be the only time,” Claussen said. “[Most of the time] things don’t need to escalate to something like calling the police.”

Additionally, the Iowa City City Council passed a 17-point resolution that addresses topics from affordable housing to police reform. John Thomas, the District C representative on the council, advocates for restructuring the police department towards community-oriented policing. He mentioned that whether it’s homelessness or people with mental health problems, the city has defaulted to using the police in the past.

“[Police] aren’t mental health professionals,” Thomas said. “If you have a person on the street experiencing some mental state which is causing disruption … is a police officer really the best person?

Though police compliance and the recent initiatives are a step forward on both a local and national scale, Mohamed believes the fight is far from over. In spite of the journey ahead, she says the increase in racial discourse is a step in the right direction.

“A lot of people’s eyes are starting to open, and they’re starting to see what is going on, what the problem is, and they’re starting to take action,” Mohamed said. “We’re also educating them as well on how they can take action. I feel like that’s one of the biggest changes that I saw. People are asking, ‘What can I do?’, [and] I think that’s very important.”