Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

As car crashes are the number one cause of death for teenagers, many question whether teenagers are ready for the responsibility that comes driving.

Accelerated

With the privilege of driving comes immense responsibility — especially for teens in Iowa, who can drive alone starting at just 14 years old. Some worry whether they can handle the pressure of navigating the roads.

April 24, 2021

On a typical morning at West, it’s no surprise to see a stream of cars pulling into the parking lots, followed by dozens of students walking into school, jangling keys in hand. For many, being able to drive oneself to school seems like a rite of passage.

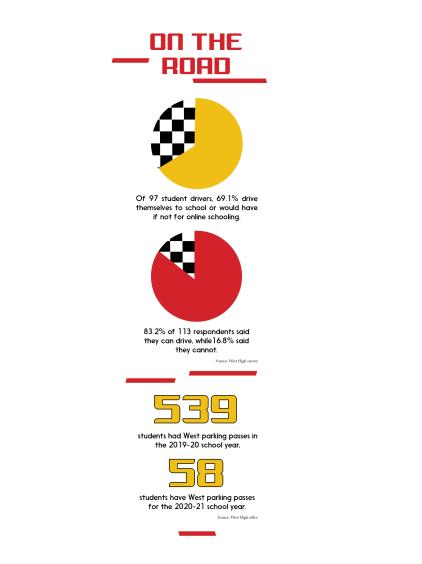

However, this newfound independence may come at a price. Nearly 20% of 71 West High students surveyed have been in a crash while at the wheel. Starting at age 14 and a half, the state of Iowa allows students to drive alone to school and school-related extracurriculars as long as they have completed driver’s education and have held a learner’s permit with a clean record for six months. This age requirement is the lowest in the country and may raise questions as to how much teenagers can be trusted with driving.

Teenage trends

With teens eager to obtain a license and gain independence, many consider driving an entitlement rather than a privilege. However, this possibility often depends on a family’s socioeconomic status.

More than 86% of 16 to 18-year-old drivers from households with an annual income of over $100,000 were licensed or had a learner’s permit, compared to 57% of teens from households making $50,000 or less, according to a study by The Zebra, a car insurance company.

However, the overall teen driving rate has decreased over the years. According to the University of Michigan, 71.5% of high school seniors had a license in 2015 compared to 85.3% in 1996.

One explanation for this decline is that teenagers have opted for online rather than in-person hangouts with friends, decreasing the need for a car, according to another study by the University of Michigan.

From a parent’s perspective, a self-transporting teen provides convenience for the household. According to the Iowa Department of Transportation, in 2014, about 90% of parents signed waivers exempting their teen drivers from the intermediate license restriction of allowing only one unrelated minor passenger in the vehicle without adult supervision.

“It’s overwhelming if you have multiple kids who [need] to be driven all over,” Carney said. “As soon as kids [are] able to get a school permit, I think a lot of families feel relief.”

When teens do obtain a permit, their driving habits often mirror those of their parents.

“Kids start mimicking parent behaviors from a really young age, so whatever’s learned about the prioritization of safety is probably well established even before driving,” Peek-Asa said.

Peek-Asa believes driver’s education can impact this prior learning with different methods than currently employed.

“Driver’s ed programs focus more on how to maneuver the car and less on safety,” Peek-Asa said. “Often, they’ll approach safety by showing a lot of pictures of crashes, which from a learning neurobiology standpoint isn’t a great way to encourage [safer] behavior.”

Parental influence also plays a role when determining the time a teen gets their permit. Alarape wanted to get a permit at age 14, but her parents were reluctant to allow her to start driving.

“I had to get my permit a year later because it took a lot of convincing [for my parents] to let me go,” Alarape said. “I think they were just kind of in denial about the fact that their child is growing up.”

Peek-Asa views driving as a chance for teens to take initiative in their actions.

“Some parents are not the best role models in driving, and teens can see that and choose to act differently,” Peek-Asa said. “It’s an opportunity for teens to really make their own choice.”

Peer pressure

While scrolling through Instagram, you’ve likely come across a post captioned with “stay off the roads!” to celebrate the birthday of a newly 14-year-old friend. With this opportunity, 68.4% of 93 West High student drivers surveyed started driving right at age 14.

Out of 102 responses from the survey, 37.1% said they feel or felt peer pressure to begin driving at a young age.

Favour Alarape ’21 experienced this unintentional peer pressure before she started driving.

“It’s kind of weird when everyone pulls up to school, and then you have your mom that dropped you off, and your friends are walking out to the parking lot, and then you’re just walking to your mom’s car,” Alarape said.

After witnessing her peers start driving, Kamakshee Kuchhal ‘24 began feeling pressure to drive despite hesitation.

“Watching all of my friends get their driver’s [permit] before me and talk about driving can make me feel a little bit left out,” Kuchhal said. “When my friends say, ‘Want to go to the courts to practice together? I can drive there,’ [I] feel self-conscious about telling them, ‘I have to ask my parents first, and I’ll get back to you.’”

However, Neena Turnblom ‘23 has not been influenced by this pressure.

“I don’t feel that there is a peer pressure to start driving because I haven’t yet, and everyone I know is fine with that,” Turnblom said.

According to Alarape, peer pressure can also cause drivers to make risky decisions. Since Alarape is younger than many of her friends, she had her learner’s permit when they had their intermediate licenses. As a result, she felt inclined to violate her permit’s restrictions.

“Some of [my friends] were 16 at the time, and I was like, ‘Oh they’re driving without adult supervision on a license … I could probably do that too. [If] they can do it, I can do it,’” Alarape said.

Alarape has also noticed a larger trend of teen drivers making unsafe choices to gain social approval.

“Some people, when they’re in the car with others, pretend they’re excellent drivers and [drive] one-handed and look at their phone at the same time,” Alarape said. “Sure, you look cool, but you won’t look cool if you get in an accident.”

Too young to drive?

The feeling a teen experiences when driving alone for the first time is often one of liberation. On the other hand, some question if teens are ready for this amount of responsibility.

Being a largely rural state contributes to why Iowa allows teenagers as young as 14 to obtain a learner’s permit, as families rely on them to operate farm machinery. However, in more urban areas such as Iowa City, some feel this age is too young to safely navigate the roads.

According to Corinne Peek-Asa, director of the University of Iowa Injury Prevention Research Center, the teenage brain lacks the development necessary to make the safest decisions while driving.

“It’s really difficult neurobiologically for teens to turn off the emotions and turn on the frontal lobe, which is something that has to happen when you’re making quick decisions when driving,” Peek-Asa said.

Ali Burgess ’21, who doesn’t have her learner’s permit, believes 14-year-olds aren’t ready to take on the responsibility of safe driving.

“I don’t think that [14] is a good age to start driving … I feel like a lot of teens in that age range get into drugs and [bad habits],” Burgess said.

However, Ashley Seo ‘23, who is 16 and has also yet to obtain a learner’s permit, sees the ability to handle this responsibility as dependent on individual drivers.

“I would not trust a 14-year-old to drive me … because I think it’s generally unsafe and a little young in terms of maturity or responsibility,” Seo said. “But people who do [drive] at 14 and choose to take on the responsibility, they can probably handle it.”

As a 14-year-old herself, Kuchhal believes there is still risk involved with letting people her age drive.

“I get a lot of anxiety because there are just so many things that could go wrong, especially knowing that there are people out there my age who might be handling a car,” Kuchhal said.

Kurt Crock, who has been teaching at Mount Vernon Drivers Education since 2018, believes teenagers as young as 14 are capable of driving but with limited privileges.

“I would not be in favor of 14-and-a-half-year-olds being allowed to drive anywhere anytime,” Crock said. “[But] allowing them to drive to school is a great training ground where they [get] safe hours behind the wheel.”

Cher Carney, a senior research associate at the National Advanced Driving Simulator at the University of Iowa, found through her studies that experience is more important than age in terms of safe driving. In one study, Carney compared 14-and-a-half year olds who had just gotten a school permit with 16-year-olds who were getting their license, and 16-year-olds who had a year and a half of experience.

“What we found was it’s not really how young or old you are, it’s the amount of experience you have,” Carney said.

Emma Caster ’21 has been driving for three years and feels her experience allows her to make riskier decisions with a slimmer chance of facing negative consequences.

“I have driven with distractions because I was confident in my abilities as a driver to keep everyone in my car and outside my car safe,” Caster said.

However, driving experience may lead to overconfidence in some teens. According to a 2015 study by the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, it is drivers aged 16 to 17 that continue to have the highest number for crash involvement rates.

Crock believes this is because as teenagers become more comfortable with driving, risky behaviors become less of a concern.

“By the time they’re 17, hanging out with their friends on a Friday night … they’re not the same type of driver they were when I’m sitting right next to them,” Crock said.

Driving dangers

“I was on my way to school, and I hit a school bus.”

It was an icy winter morning, and the roads were slippery. Alarape was driving faster than she should’ve been.

Her crash was one of the 156,164 annual crashes due to icy roads, as reported by the Federal Highway Administration. Luckily, the bus was empty, and after her experience, Alarape became more careful while driving in ice and snow.

“I drove cautiously and slowed down a lot on my turns, especially because it was winter,” Alarape said.

Other than weather-related reasons, distractions are also a major cause of car accidents. Of 71 student drivers at West, 68.1% report driving with notable distractions, and 54.9% text while driving. A quarter of car accidents in the U.S. are caused by texting and driving, according to the National Safety Council.

“I don’t [text and drive] because you’d have to be an idiot to do that … [it] increases the chances of [a crash] by so much,” said Miles Clark ‘22. “If I close my eyes for a second while driving, I’d end up in a completely different place, so I don’t see why looking down at your phone wouldn’t do the same.”

Though many are aware of the risks of texting and driving, an anonymous source notes that phone addiction and habitual checking may override that understanding.

“Sometimes I accidentally [check my phone] out of habit, and then I have to stop myself because I feel like driving has become pretty second nature,” the source said.

Another distraction that affects many teen drivers is driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol. A study by the CDC found that one in 10 high schoolers drink and drive.

The anonymous source has driven under the influence of alcohol, cocaine and marijuana.

“I usually try to be rational with myself about it … I know the statistics and how many accidents are caused by that, so I just really, really try to avoid that,” the source said. “But I have waited a bit after consumption, and then kind of assess myself like, ‘Do I think I can drive my car?’ I’ll test myself before I start driving.”

In the U.S., according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, about 28 people die in a drunk-driving crash every day. Under the influence or not, Clark believes teens make unsafe decisions because they believe the consequences won’t affect them.

“[People who make unsafe choices] completely disregard the bad things; they think about the benefits, they don’t think about the downsides,” Clark said. “Even though they acknowledge that the downsides exist and they agree with it, they just don’t think about it.”

While many teen drivers try to avoid distracted driving, it can sometimes prove inevitable. Carney believes busy highschoolers’ cars can act as a place to carry out everyday tasks.

Alarape often eats breakfast while driving to school and feels driving the same daily route helps her multitask.

“Most of the time [when eating while driving], I’m on my way to school. I’ve gone down this road so many times, so I’m pretty sure I’ll be okay,” Alarape said.

Due to her busy schedule, Alarape has had to drive after taking sleep-inducing Tylenol, which caused her to make some errors.

“I shouldn’t have been driving because I was falling asleep … [but] I had places to go,’” Alarape said. “I think I ran a red light. I was so focused on the cars in front of me that I stopped paying attention to the signs.”

Alarape is not alone, as more than 40% of U.S. drivers have fallen asleep behind the wheel while driving, as reported by the National Sleep Foundation. Additionally, driving impairment after 24 hours without sleep is equivalent to having a blood alcohol content of 0.1%, which is above the legal limit of 0.08%, according to the Sleep Foundation.

To prevent nighttime crashes, teens holding intermediate licenses are restricted from driving alone between 12:30 a.m. and 5 a.m. Even though most teen driving takes place during the day, a third of fatal crashes with teens at the wheel still happen after dark, according to the CDC.

Traffic accidents also affect those outside of the vehicle. The Federal Highway Association found that pedestrian and bicyclist deaths account for 16% of all annual traffic fatalities.

Brenda Gao ‘21 finds the West High parking lots, crowded with teen drivers, to be potentially dangerous.

“I take caution stepping out into the parking lot and walking across it because drivers can be rushed to get out quickly, especially in the back lot where people want to get out before the buses,” Gao said.

Though teenagers’ mentality and inexperience can compromise their ability to drive as responsibly as veteran drivers, Peek-Asa believes safety should remain the number one priority for anyone operating a vehicle.

“I think everyone has the potential to be a good driver,” Peek-Asa said. “The problem is when people don’t pay attention, don’t take driving seriously or prioritize speed over safety.”