Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Breaking barriers

Sports at West can build bridges for ELL students, but only if they can make it past the barriers.

October 7, 2021

Friendship. Comradery. Sense of belonging. High school athletics offer students a built-in community, support system and the chance to represent their school. Unfortunately, many students with talent, athletic capability and work ethic never get the chance to wear a green and gold jersey, as cultural and linguistic barriers may prevent them from gaining these sport-related benefits.

“The District’s English Language Learner Program (ELL) serves approximately 1,750 students in grades K-12 from more than 70 language and cultural backgrounds,” according to the ICCSD’s website. “The mission of the ELL program is to produce language learners who are socially and academically prepared for success in the District and in a global society.”

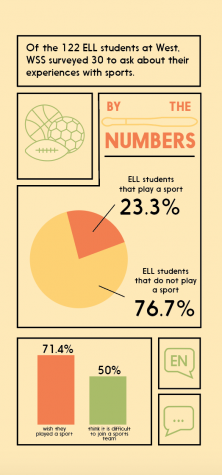

Of those 1,750 students, there are 122 ELL students currently taking an English language development course at West High. Some ELL students at West are not involved in sports because of the challenges they face. However, once they break these barriers, there can be multiple benefits.

Sporting benefits

A large and diverse school such as West High can initially intimidate almost any student, so a sense of belonging is necessary for individuals to feel comfortable at school. Learning English while adjusting to West only exacerbates this challenge. Athletics offer a welcoming place for those who participate, including many ELL students. Soccer helped former ELL student Ben Nkolobise ’22 find a place in the West High community.

“Playing sport made me actually connect with people,” Nkolobise said. “When I joined sports, I started to make new friends. People started knowing me.”

Similarly, joining track opened social doors for Hebah War ’23. The sport allowed her to branch out and make new friends even beyond West’s boundaries.

“I make a lot of new friends. Every time we go to a track meet, I like talking to the people there and getting to know what they like doing,” War said. “It just makes me feel like I’m out there and making new friends.”

ELL student Juan Martinez ’22 looks forward to also meeting new people, as he plans to participate in West athletics and play soccer for the first time this spring.

“I’m excited to meet new people and just build a community with people,” Martinez said.

When ELL students actively participate in sports, ELL teacher Jessica St. John notices an improvement in student behavior and mood due to team interactions on their sports teams.

“They have a sense of belonging; they’ve met friends outside of the ELL program and their demographic,” St. John said. “They [feel] they’re a part of the West High family.”

Matt Harding teaches physics and ELL science at West in addition to being a soccer coach. He recognizes the importance of extracurriculars in fostering a sense of place for ELL students.

“Whatever extra activities they can participate in … really help with that sense of belonging,” Harding said.

Additionally, being on a team fully immerses ELL students in an English-speaking environment, pushing them to improve language skills through communication.

“It’s a great thing to motivate them to get out of their comfort zone a little bit, turn on language and really have to practice English,” Harding said.

According to the 2014 ICCSD ELL program analysis report, 63% of the 283 ELL students surveyed said that talking with a partner in English improved their language skills the most. This is reflected in St. John’s classroom.

“Students are more talkative [during the sports season], and depending on their English level, that might be huge. They just have a lot of confidence, and honestly, they’re just overall happier,” St. John said.

St. John’s perspective stems from real athletes’ experiences. Nkolobise felt improvement firsthand while playing soccer and communicating with more people.

“When I was around people, I was learning new words and making friends. [Playing sports] really helped,” Nkolobise said.

War believes that improvement in language learning is one of the most beneficial parts of playing a sport. She encourages her ELL classmates to join for this reason.

“I know speaking English for some people is really hard, but talking to people and making new friends helps. It makes [students] feel comfortable around people [while] practicing English,” War said.

Obstinate obstacles

Even though sports provide a sense of comfort and unity for ELL students, there are many barriers that make it difficult to get involved. Of the 30 ELL students surveyed, 70.4% of the students wish they played a sport, but 50% believe that it is difficult to join a West high sports team. Something as simple as completing the proper forms to practice presents a unique challenge for some ELL students’ families.

“[ELL students] miss the tryouts because they didn’t get the physical, or they didn’t know whom to contact,” St. John said. “A lot of people don’t know how to navigate those things.”

An even bigger challenge is that, unfortunately, not all students feel comfortable even trying a sport.

“There’s a lot of kids that don’t do sports because they probably don’t speak English, and they’re scared,” Nkolobise said. “They can’t express themselves.”

Gali Flores ’22, who helped guide an ELL student through this past soccer season, has a similar opinion from an outside perspective.

“I think that for someone who doesn’t speak English, it’s much harder to join clubs and get out there,” Flores said. “They feel like they won’t be able to communicate with others, make friends or … fit in.”

Since communication is one of the most crucial aspects of playing a sport, a language barrier can prove to be challenging within the game. Flores used her Spanish to help guide an ELL teammate this past soccer season.

“I definitely feel like it was hard for her and the other teammates because they’d [give directions], and she wouldn’t understand,” Flores said. “That was another challenging part of it.”

There are also more challenges to fitting in that extend beyond language.

“When students come here from another country, they’re already like, ‘Oh my God, I feel different than everybody else,’” St. John said. “They don’t realize that they have the possibility to join a sport.”

For many sports, tight-knit communities already exist within the West team. Joining from the outside can make the process even more intimidating.

“Many of [ELL student’s] teammates have grown up playing together,” Harding said. “It’s a challenge trying to break into some guys that are very familiar playing with each other and not so much familiar with you.”

Being on a team extends beyond competing on the field. Group activities and spending time together are crucial to building the sense of community that brings teammates together. However, as Flores looks back on helping her teammate, she believes it is especially difficult for ELL students to get involved in team bonding.

“I definitely feel like she missed out on some stuff like team dinners and photos and such. Just gatherings that we would have because I feel like no one would really reach out to her on the team. So that was another challenging part of the language barrier through sports,” Flores said.

Participating in sports comes with added responsibilities that can put stress on other aspects of student life. Nkolobise notes that school can be harder to manage when you’re in season, especially while also trying to learn a language.

“When you have sports after school, it might be hard to manage [learning English] and focus on school,” Nkolobise said.

Along with academics at West, he has even more responsibilities that take up time and effort outside of school. For Martinez, finding this balance has been difficult but rewarding.

“I have a lot of siblings that I have to take care of, and there’s a lot of homework to get done. I have a lot of responsibilities,” Martinez said. “I found out how to manage that stuff and now I’m going to be able to play this year.”

Although participating in a sport can come with great challenges for ELL students, War believes it is worth it in the end.

“It was scary at first… but throughout the season, you get comfortable with people,” War said. “It’s welcoming, and you can be yourself.”

Initiating improvements

Although there are both challenges and rewards from playing sports as an ELL student, St. John believes there are several ways to make West athletics more accessible to ELL students.

“They could make the registration easier and have the forms in paper copy. I think that would help the students have all the forms in one place,” St. John said.

Teachers can help by finding out what their students like and encouraging them to get involved in sports.

“I think it’s really important to take a proactive approach [to make sports more accessible]. You can’t just treat [ELL students] like a general education student and expect that if it’s of interest to them, they’ll actively pursue going out for it,” Harding said. “I think it’s important … to make those connections for the kids and really check in with them.”

War also thinks that if coaches would make a greater effort to reach out to ELL students, more students would feel more accepted.

“[Coaches] should come to classes and talk to people more, like actively reach out to people and tell them that this is a safe place and they can come,” War said.

Flores believes that students can reach out and recruit as well.

“Students should do a better job of [saying] ‘Hey, you can come join [sports]. Everyone’s welcome, [and] we’ll help you out,’” Flores said.

Once ELL students join, Harding believes that teammates, like Flores, have a crucial role in engaging their teammates who are struggling to get involved.

“The players in the program have to look out for their new friends … making sure that they can get to practices or games that aren’t on-site,” Harding said.

Harding encourages coaches to keep diversity in mind and make adjustments accordingly.

“The first thing is to look at the diversity of your roster compared to the diversity of the building. If you don’t see alignment there, then reflect on what is serving as a barricade, a barrier for participation for those ELL kids,” Harding said. “The next step is trying to address them.”

Making ELL students feel included lets them feel comfortable in what may be a challenging environment. Harding believes that if West makes the process of joining a sport more accessible and welcoming, they might be one step closer to putting on a green and gold jersey.

“I have such limited experience with being in situations where the majority of people around me don’t look like me, don’t talk like me,” Harding said. “So for [an ELL] teenager to have to experience that every day, anything we can do that can help them feel more a part of the community is really important .”