Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Language logistics

Language is integral to communication — whether it’s learning English, a foreign language, or connecting back to one's roots, each student has a unique experience.

January 25, 2022

A school district in southeast Iowa is probably not the first place someone would think of as “diverse.” But the ICCSD, with a white student population of just under 57%, is a notable exception. From French to Arabic, students across the district speak over 90 languages, according to its 2019-2020 demographic report. Many students are bilingual, trilingual or even polyglots, people who speak several languages. Others are trying to learn a second language or simply reconnect with their origins.

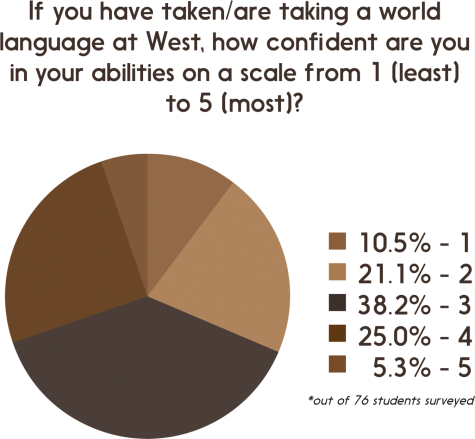

For most high school students across the country, learning a foreign language is a requisite for graduation, college admissions or both. According to a West Side Story survey with 76 responses, more than 90% of West students are learning at least one new language. Currently, the ICCSD offers two languages: Spanish and French.

Helen Orszula ’24 took French I her freshman year. Her experience on Duolingo, a language learning app, was one factor that helped her test into French II for the last trimester of that school year. Only a month into her sophomore year, Orszula transferred from French III to AP French.

“I think my main problem was that we weren’t moving fast enough,” Orszula said.

Similarly, some students noticed a lack of new material being introduced as they progressed through the language curriculum. From conjugations to sentence structure, teachers often review lessons from year to year.

“In the Spanish curriculum, I feel like we have repeated many lessons from eighth grade to ninth grade. We should move not faster, but in a different direction,” said Vinicius Marra ’24.

Others, like Spanish learner Anna Verry ’22, found value in the slower pace in helping to build foundational skills.

“Having that slow pace at the beginning really set us up for success and later classes because we were really focusing on the basics,” Verry said.

Like other classes, some students who were a part of the online program last year struggled to keep up with their workloads in Spanish and French.

“The assignments didn’t feel real so I kind of put them off,” Orzula said. “Being in a classroom with other people really helps me.”

Aidan Ohl ’22 took AP French online last year. Despite getting high grades in the class, he opted out of taking the AP exam.

“There’s a couple exceptions, but really, it just felt like everything was based on writing and prepared speech. I think that’s only really half of being fluent,” Ohl said. “So my grade, despite being good, didn’t actually reflect the fact I didn’t feel great about my skills.”

Verry, who took AP Spanish in person last year, shares a similar sentiment.

“I don’t feel confident enough to go to a native speaker and have a conversation with them,” Verry said. “I feel like if I were talking to other students in my class, I would be able to converse with them because I know we’re on the same playing field.”

Spanish II and AP Spanish teacher Monica Aparicio Ruiz thinks that a focus on speaking, listening and utilizing what students learn in class is key to successful language learning. However, she believes that practicing outside of the classroom is also essential.

“Many times, we only use the language in the classroom and then we don’t take it out with us,” Aparicio Ruiz said. “We need to put more of an effort into practicing outside of school.”

Aparicio Ruiz suggests volunteering in local Spanish-speaking communities as a way to gain exposure to the language. Though she advocates strongly for real-world practice, she points to alternative strategies for developing language skills outside of class.

“One thing I’ve been telling [my students] is that it doesn’t even necessarily have to be practicing with a native speaker,” Aparicio Ruiz said. “There are other ways to practice: reading, reading out loud and watching Netflix. Try to immerse yourself.”

Verry recalls Spanish teacher Jamie Sandhu encouraging her students to get extra outside practice, too.

“Even in Spanish II, Señora Sandhu really harped on finding a good podcast to listen to or going to a radio station that spoke Spanish. The reading and listening was definitely [emphasized]. It was like, ‘You should really do this if you want to be successful,’” Verry said.

Some highly-motivated students continue their studies through either the Seal of Biliteracy program or Post Secondary Enrollment Option classes after taking four years of a language. Students can take Spanish or French V, classes offered by the ICCSD, to obtain the Seal of Biliteracy, which is recognized internationally as the ability to communicate in two languages fluently. Others choose to take PSEO classes at the University of Iowa, where they can simultaneously earn credits for both their high school diploma and college degree.

Nathan Wei ’22 is a Chinese heritage speaker who is currently enrolled in PSEO Japanese. He took the class in hopes that he would learn some of the similarities and differences between Chinese and Japanese.

“I am aware that many [Japanese] words and vocabulary comes from Chinese but I wanted to see the areas that contrasted with Chinese such as hiragana and katakana, along with its grammar and honorific system that Chinese doesn’t share,” Wei said.

Wei took Spanish for four years and noticed the fast pace of PSEO courses in comparison to language classes at West. He says his teacher spends less time teaching simple vocabulary and gives far more tests and quizzes. Wei finds this faster pace more engaging and believes West classes should follow suit.

“Teachers should pace the students and teach things more quickly,” Wei said. “The reason why Spanish was sometimes more mundane was that the vocab and conjugations were taught too slowly and I was given too many class days to learn it.”

With 1.5 billion speakers globally, English is the most widely spoken language in the world. Although the U.S. does not have an official language, English is predominantly used in the government, educational resources and media. It can be difficult for students not fluent in English to integrate into the community.

“In the beginning, it was a challenge because language is really important,” said Marra, a native Portuguese speaker from Brazil. “I feel like there was a barrier. I was really shy in the beginning, so it was a little difficult to make friends.”

The English Language Learning program can help students like Marra with this social barrier.

“Many people from different cultures were [in ELL] and it was a good experience for me because, together, everyone was trying to learn English and I didn’t feel alone,” Marra said.

Another potential challenge for students and families who are not native English speakers is communicating with the school. Although there are accommodations, such as interpretation and translation services, some believe the district can do more. Adrian Rodriguez ’24, whose parents are not completely fluent in English, has noticed a lack of communication in other languages.

“Every email that the school has sent has been in English. I never see them in Spanish,” he said. “I think [the district] should add emails in other languages … it would be a great improvement to the whole district if they would be able to do that,” Rodriguez said.

The communication barrier extends to academics as well. Keeping up in classes taught in English as a non-native speaker can be demanding, especially in subjects heavy on reading and writing.

“During an APUSH test or English test, sometimes I don’t understand some English words, but over time, that has [happened less],” Marra said.

However, the language barrier hasn’t stopped Marra from taking on a challenging course load or standardized tests.

“I like to challenge myself and I think my English is improving every year,” Marra said. “I think you always need to try your hardest and find the things you find difficult and make them easier.”

On the other end of the spectrum, there are students learning languages they are already very familiar with. Dr. Giovanni Zimotti, director of Spanish Language Instruction at the University of Iowa, says that language classes can be difficult even for those who can already speak fluently.

“When you go to school, you get hours and hours of English grammar here in the United States. And for [Spanish heritage speakers], the only Spanish they’ve been speaking was the Spanish they were speaking at home … so they can speak Spanish, but they have some issues with grammar because they never learned it,” Zimotti said.

Native speakers learn a language through the formal education system of the country they were born in. It is often the first language they have learned. On the other hand, heritage speakers are informally exposed to the language at home through their families. It is not usually their first language, and they use a different language in their daily life outside of home.

Rodriguez moved to the U.S. from Cuba when he was 9. Although he is a native Spanish speaker, he still finds that not all of the AP Spanish content comes naturally to him. He has noticed that writing and analyzing readings are the hardest parts of the class as he isn’t accustomed to using Spanish in an academic setting. He also noted the Spanish taught at West is more formal than what he uses on a day-to-day basis.

“[The teacher] showed us an example of writing this formal letter,” Rodriguez said. “There were words that I never use at home.”

Aparicio Ruiz, who is also a native Spanish speaker, believes this is an important distinction.

“We have to take into account that the Spanish we are learning here is very much Spanish used in academia,” Aparicio Ruiz said. “Of course there’s going to be so many dialects and slang that [native speakers] might be aware of but that we don’t necessarily use when writing a letter or presentation.”

Although not everything taught in language classes feels familiar to native and heritage speakers, the AP curriculum places a strong emphasis on cultural learning. This provides some students with the opportunity to connect to their own culture.

“It’s a language that’s connected to [native speakers] personally. It provides an opportunity to communicate in the language that their grandparents speak,” Aparicio Ruiz said. “It carries sentimental value [and it is] important to me that my native speakers are able to connect with that.”

From communicating with native speakers to future job offers, learning a world language opens the door to many opportunities. Because of this, Verry feels the ICCSD should place a greater emphasis on the importance of language.

“I’ve seen the benefits of knowing another language and I think a lot of people have, so I think there should be more of a focus on learning another language for the benefits [when you] go out into the real world,” Verry said.

Despite there being thousands of languages spoken globally, the ICCSD offers just Spanish and French as high school classes. ICCSD World Language Coordinator Carmen Gwenigale attributes this lack of diversity to the district’s limited budget.

“At one point in time, we had three languages, and due to budget cuts, we lost German. Teaching French and Spanish, Arabic, Chinese and German … would be ideal,” Gwenigale said.

Verry agrees having more languages to choose from would be beneficial, especially because it would allow students to pursue what they are interested in.

“Giving the students more options would help boost motivation to want to learn,” Verry said. “If they want to learn German, give them that opportunity, because you know they’ll work hard because they’re passionate about it.”

In addition, Paige Nierling ’23 thinks the ICCSD should offer American Sign Language as a class. Nierling learned ASL to better communicate with her brother, who is deaf, and believes sign language is an important skill.

“[My brother] is really lucky because he can read lips and has hearing aids, there’s so many people out there that [can’t] … sign language is just a good thing to know,” Nierling said.

According to the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders, around one in eight people have some degree of hearing loss in both ears in the U.S., yet only 500,000 Americans know ASL. Nierling’s brother finished elementary school in the ICCSD before transferring to Iowa School for the Deaf in Council Bluffs. Through her brother, she saw how a more inclusive environment results in better experiences for those with trouble hearing.

“[At the] deaf school, he was just more included with people that he could relate to more. He had some bullying problems in elementary school because of his hearing problems and … it’s a difficult thing for anyone to go through anything like that,” Nierling said.

Aside from curriculum changes, some believe language learning itself should start earlier. According to a 2017 report from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, students in the U.S. have less access to foreign language instruction than students in other developed countries, and Americans are much less likely to be bi- or multilingual. This is sometimes attributed to the fact that many districts in the U.S. begin language instruction in junior high or high school.

“I would advocate for language learning at an earlier age,” Aparicio Ruiz said. “It has been proven basically that the earlier we start learning the language, the more it’s a part of our life and the easier [it becomes]. If it’s something that starts early on and continues throughout your education, I think there’s a lot of benefits.”

Younger children have greater brain plasticity, which is the ability of neural networks to change through growth and reorganization. This is why many other countries mandate foreign language learning very early on in students’ education. Data from Pew Research shows that almost all students in Europe study their first foreign language by age 9 and a second one later on. Because of this early start and a greater emphasis on language learning, 92% of European students know multiple languages. In contrast, this number is 20% in the U.S., which does not have a national requirement for language proficiency.

“If students started learning languages from elementary, their brains are just so malleable at that time to take things in. The younger they are, the more open they are to embracing new concepts,” Gwenigale said. “At that place, too, they’re not afraid of failure. In high school, there’s so much attachment to grades and students shut down right away when they feel or see anything as a failure. In elementary, when the grade is not a factor, it’s just the learning that is the factor, there’s a higher probability for success.”

Not only does language learning open up new opportunities, it also enhances cognitive thinking. Due to the daily exercise of learning another language, multilingual children often have better memories than monolingual children. They outperform in terms of “metacognitive awareness, problem-solving, flexible thinking, and attention span,” according to Science Times.

Verry, who is co-president of the 1440 volunteering club, sees community-building as one of the most important benefits of learning a language from her time working at a nursing home.

“The importance of learning a language is not only to benefit you … but it’s also to benefit other people and can make sure they feel comfortable in the environment that they’re in,” Verry said. “Learning a language makes the community more tight-knit as more people can converse with each other.”

The learning process is a long journey. New vocabulary, grammatical systems and pronunciation pose obstacles for those looking to become fluent. However, Gwenigale believes the end result of learning a language is worth it.

“[We] really want students to embrace the idea of learning a language as a gift, and not as just a check-the-box [to get out of college language classes],” Gwenigale said. “When we teach language, we’re not just teaching you how to communicate, but we’re also teaching you the culture. We’re teaching you how to be accepting of differences: different identities, different cultures, different ideas, and understand different perspectives.”