Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Equal footing

West High athletes reflect on the underappreciation and oversexualization of girls sports and how they impact athletes’ performance.

January 24, 2022

It is the final meet of the season — hundreds of hours dedicated to a three-minute race that determines whether her team takes home the state title. A disqualification in the form of a false start or a botched relay exchange looms in the back of her mind, but she is confident in her team’s training and focus. Little does she know, one of the only things that could stop her is out of her control: the way her swimsuit fits her body.

Troubled waters

At the Mississippi Valley regionals swim meet Nov. 6, an official approached a West varsity swimmer and asked her to pull down her swimsuit because it revealed too much of her body.

“A swimmer told [the official] that it’s just her build, that’s how her body looks,” said varsity swimmer Olivia Taeger ’22. “The official continued to stand there and essentially harass her because the fact that her swimsuit fit her like that was making the official uncomfortable.”

According to the Swimming Officials’ Guidelines Manual, which the Iowa High School Girls Athletic Union follows, officials are allowed to disqualify swimmers if their swimsuit is deemed “non-compliant.” The manual reads, “Bring non‐compliant suit coverage violation to the attention of the coach. The competitor or coach may be notified of suit construction violations. Coaches should be reminded of what is not permitted to be worn or displayed during competition.” The manual does not specify further on the topic of uniform regulation.

Ella Hochstetler ’22, a swimmer also present at the regional meet, noticed that the vagueness of this rule allows for officials to abuse their power.

“There’s no measurements or anything,” Hochstetler said. “It’s completely subjective to each official, and they can be as loose or as tight [with the rule] as they want to.”

Hochstetler believes swimmers have no control over situations involving suit infractions. Additionally, a disagreement with an official can put a swimmer’s career at risk.

“You also don’t want to get into conflict with an official because if you do, that can impact the rest of your season,” Hochstetler said. “If they disqualify you, or if you get in trouble somehow with the state, it’s really not a good thing. There’s not really that much power we have on that sort of thing.”

While the swimmer was not disqualified, Taeger started a petition on Change.org to remove the coverage rule after the incident at the regional meet.

“All people are built differently. Your body shouldn’t prevent you from being able to swim a legal race,” Taeger said.

She hopes the petition will spread awareness of the situation and bring about the manual revision.

“I just don’t want other female swimmers to feel the discomfort that I felt from being on the pool deck, because you should be able to race and have fun and not worry about how you’re looking,” Taeger said.

Athletes, not objects

“Sport appeal, not sex appeal.” This was the mantra Olympic broadcasters used at the 2021 Tokyo Games to prohibit sexualized media of female athletes at the Olympics. According to the Portrayal Guidelines issued by the International Olympic Committee in July 2021, news companies should refrain from “focusing unnecessarily on looks, clothing or intimate body parts,” while “respecting the integrity of the athlete.”

Volleyball player Sydney Woods ’22 believes the traditional cut of women’s sports uniforms leads to the sexualization of female athletes.

“I think a lot of girls’ sports are very sexualized, especially the uniforms, like swimming, gymnastics, dance and volleyball,” Woods said. “I feel like that’s just how those sports are made. So whenever people think of volleyball, they think of our bodies because we wear short, tight shorts.”

While at school or cheering at football games, cheerleader Alexa King ’23 has also experienced the effects of the cut of her uniform.

“People at school just stare at us because of our uniforms, especially [our] skirts that are really short,” King said. “It’s very uncomfortable.”

Tatiana Schmidt ’23, who has danced at a competitive level for eight years, has noticed the revealing nature of dance costumes starts early.

“I feel like the appropriateness of costumes is just kind of stagnant, so little kids will often wear scandalous costumes,” Schmidt said. “There probably are some [adults] that are uncomfortable with the costumes. I feel like you shouldn’t really be thinking about children in that way though.”

In January 2019, UCLA gymnast Katelyn Ohashi scored a perfect 10 floor routine that soon went viral on the Internet, with the video of her performance drawing over 44 million views on Twitter. However, a portion of the comments surrounding the videos were negative ones directed toward Ohashi’s body rather than her skills. Competitive gymnast Bailey Libby ’22 has experienced objectification while training at her gymnastics club.

“I used to train with the boys [gymnastics team], and they would stare at our bodies all the time [and] make comments about what we’re wearing because we train in sports bras,” Libby said. “They made it very uncomfortable to train and feel like yourself in your body.”

Cross country and track athlete Erinn Varga ’24 has also experienced this double standard. During a run on Camp Cardinal, the girls cross country team was whistled at while training in sports bras.

“It’s so normalized in our culture that [the boys team] can take off their shirts, [but] we’re automatically seen as an object for taking off our shirts,” Varga said.

Athletes have protested the historical precedent of sexualized uniforms at the professional level. At the 2021 Tokyo Olympics, Germany’s female gymnasts protested the sexualization of women’s uniforms by wearing full-body unitards instead of the common bikini-cut leotards. However, there were consequences for breaking the rule manual. In November, at the European Beach Handball Championships, the European Handball Federation fined each member of Norway’s women’s team 150 euros for wearing shorts instead of the required bikini bottoms.

Taeger believes the way uniforms fit athletes’ bodies leads to the invalidation of athletic ability.

“Oversexualization happens a lot in swimming … and a lot of it just pertains to how girls’ uniforms fit their bodies,” Taeger said, “and I think a lot of the audience of the sports aren’t as interested in how [athletes] actually perform, but how they look while they perform it.”

Wrestler Jannell Avila ’23 agrees that an athlete’s success should be recognized rather than their appearance.

“Women’s wrestlers wrestle because they enjoy the sport, and people should recognize them for the success they’re having instead of the way they look while doing it,” Avila said.

At the girls swimming regional meet, the effects of this rhetoric were made clear.

“This girl’s amazing swim that had a seeded top three in the state didn’t matter anymore because the only thing that mattered was her body,” Taeger said.

Unbalanced

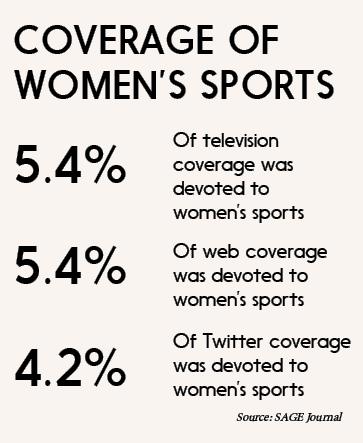

Women’s sports have historically been less prioritized compared to men’s sports in the media. According to a Purdue University study in 2019, researchers found that 95% of total television coverage focuses on men’s sports.

At the professional level, media coverage is one of the largest forms of revenue and resources for athletics. Libby believes the viewership of some womens sports is not maximized.

“I do think [gymnastics] is underappreciated, mostly because it’s not marketed very well,” Libby said. “It’s not ever really on TV. The only time it’s on TV is the Olympics and that’s only every four years. If your university or your club is going to market you well, then appreciation might go up.”

As a varsity basketball player, Zola Gross ’23 notices the difference between support for girls and boys sports at West.

“At the girls-boys doubleheader, there’s no one there for the girls game, and as soon as the boys game starts, the stands start packing up,” Gross said.

This lack of coverage can have an ongoing impact on women’s athletics.

“It’s an endless cycle,” Gross said. “If you aren’t getting views, you’re not going to get sponsors. If you’re not getting sponsors, you’re not going to be put on TV and therefore you’re back at the beginning. It’s just a hard cycle to break.”

Additionally, Gross believes there are many small inequalities behind the scenes. Last year, during the NCAA March Madness tournament, University of Oregon women’s basketball player Sedona Price went viral for documenting the disparity between men’s and women’s weight room facilities. The men’s teams were provided with a full room of equipment, while the women were given a small dumbbell rack and some yoga mats.

“If that video hadn’t gotten millions and millions of views, no change would have happened,” Gross said.

After persistence from the public, the NCAA apologized and provided the women’s teams with equal equipment. Woods commends West for supporting girls athletics but believes that there will always be an imbalance.

“Everything is built around [how] guys are more athletic and successful in the sports world, and I think West does a good job of balancing it,” Woods said. “Regardless, more people will always show up to the boys basketball games than the girls basketball games because of that athleticism and success aspect.”

To draw in more viewers and promote equal media coverage, ESPN made efforts to level the online playing field by launching the sub-brand “espnW” in 2010. The brand focuses on providing viewpoints and stories from female athletes. According to ESPN Press Room, espnW and ESPN accounted for 40% of women’s sports television coverage in 2019. In October, espnW launched the “That’s a W” campaign, which emphasizes the accomplishments of women in sports and seeks to put a spotlight on female athletes.

Also in recent years, professional women’s teams have been able to establish and update Collective Bargaining Agreements to make sports more equitable for women. A CBA is a written legal contract between an employer and a union representing the employees regarding topics such as wages, hours, and terms and conditions of employment.

In March 2019, U.S. women’s soccer player Alex Morgan sued the U.S. Soccer Federation, claiming unequal pay and discriminatory working conditions under their CBA. The claims under the Equal Pay Act were thrown out in May 2020, but oral arguments regarding discriminatory working conditions will be presented in early 2022.

Gross believes that gradual pushes for change are necessary for change as a whole.

“There are so many little steps that have to be taken first for any big change to happen,” Gross said. “It’s good their voices are being heard more in terms of what they want and what they need.”