Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Let’s Chat: GPT

ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence chatbot, has the potential to transform both the education system and the workforce.

April 20, 2023

Write me a 1000-word essay analyzing the Hero’s Journey in “The Odyssey.” Can you explain meiosis to me in simple terms? Give me a programming function to loop through a file. How about writing a WSS article on the implications of ChatGPT?

Since Alan Turing developed the Turing Test to measure computer intelligence in 1950, artificial intelligence has rapidly evolved and is now impacting human lives more than ever. Most recently, AI has captured the world’s attention through ChatGPT, a chatbot featuring functions from answering simple questions to summarizing entire textbooks.

About it

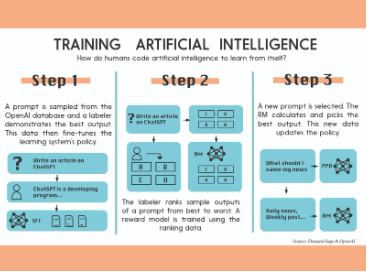

When people think of AI, the first things that come to mind likely include self-driving cars, Siri and Alexa, and a stereotypical robot. From driving to making grocery lists and working in a factory, AI systems are made to perform tasks associated with human cognitive functions. These systems learn how to perform complex tasks by processing massive amounts of data and replicating human decisions.

ChatGPT, or Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer, is a language model designed to have conversations with a user. It creates its responses based on information from the web gathered prior to September 2021.

ChatGPT was developed by OpenAI, an AI research laboratory located in San Francisco and founded in 2015. It follows several other Generative Pre-trained Transformer models made by OpenAI, the first of which was released in June 2018. Launched Nov. 30, 2022, ChatGPT is based on a model in the GPT-3.5 series and has caught the eyes of the tech community and the general public alike, garnering 100 million users in two months.

GPT-3 is free to use, while GPT-4, a new version released in March, requires a $20/month subscription. The new version has heightened abilities: it can analyze and create captions for images and graphics, has better text comprehension abilities and can solve more advanced math problems.

University of Iowa Associate Professor of Engineering Ibrahim Demir has worked with artificial intelligence throughout his career. According to Demir, ChatGPT’s novelty lies in its ability to rapidly gather, analyze and generate vast amounts of data.

“In the past, whatever model [of AI] you’re building has limited computational power to train and learn from that amount of data. But recent developments in graphical processing, unit-based computing and all the extensive data that we collect today … has allowed us to create bigger and bigger models,” Demir said. “As the model grows, [it] becomes more intelligent and more knowledgeable in the domain of everything around itself.”

The tech industry has jumped to capitalize on this expansion of AI. Since 2017, Google has also been developing a language learning model, an AI-powered conversational chatbot, Bard, which is currently in experimental form. Bard can connect directly to the Internet, meaning it has access to current information. Once the testing process is complete, Google plans to integrate Bard into Google Search.

ChatGPT can also pass tests such as the LSAT, the SAT, AP exams and medical licensing exams: on the LSAT, it scored 157 on a scale of 120-180, with 151 being the rough average for human test-takers. It scored a 1410 out of 1600 on the SAT, landing in the 94th percentile.

With AI chatbots marking a milestone in the history of artificial intelligence, their rapid expansion brings a mix of positive and negative impacts.

“I think there are many, many potential positives and at least as many potential negatives with ChatGPT,” Juan Pablo Hourcade, a professor at the University of Iowa’s Department of Computer Science, said. “Computing [has] become more and more prevalent in our lives. The big change in the last 10-15 years has been that this broadening of computing has come at a cost for people in terms of control.”

Academic intelligence

From homework-sharing group chats to the classic peek over a classmate’s shoulder, cheating methods have always been present. Recently, however, ChatGPT has emerged as a powerful tool for academic dishonesty. With ChatGPT’s research abilities and text-generating function, students are only a few clicks away from plagiarizing entire sections of AI-written work.

This reliance on AI can have detrimental effects on both students’ understanding of the material and the development of skills.

“There’s the obvious problem of [students] not learning about the topic at all … but it goes deeper than that,” Taylor Ajax ’25 said. “After a project … the teacher will be giving [students] feedback that isn’t actually what they need. Even if they understand the topic really well, they won’t be getting better at writing.”

English teacher John Boylan recognizes the risks of ChatGPT but believes it ultimately won’t pose a huge problem.

“I wasn’t too worried about it because I feel like in the past … plagiarism has been so easy to detect,” Boylan said. “I’ve always believed that my best teaching requires original student thought.”

Boylan believes offering his support and guidance as a teacher throughout the writing process can reduce the likelihood of a student resorting to ChatGPT.

“I think students use tools like ChatGPT, SparkNotes or Googling essays when they feel a certain amount of desperation,” Boylan said. “If I can minimize that as much as possible, I’m not too worried about it.”

According to a survey by Study.com, an online learning platform, 26% of teachers have caught a student cheating using ChatGPT. When it comes to written assignments, plagiarism detectors like Turnitin and OpenAI’s Text Classifier can find cheating. However, there are already methods students can use to bypass these checks, whether it’s manual alterations of AI-generated texts or paraphrasing tools like QuillBot.

“If you put [the text] through QuillBot and … Grammarly or something, and then use synonyms for a bunch of words, all of sudden [teachers] can’t detect AI anymore,” Ajax said.

Built by Princeton University senior Edward Tian, GPTZero is a highly-publicized AI detection tool that has been released to the public in the beta stage. It works by measuring two variables, “perplexity” and “burstiness,” that appear at higher levels in human-produced writing. Still, the tool is not entirely accurate. In a study conducted by a science and technology website called Futurism, GPTZero correctly identified the ChatGPT text in seven out of eight attempts and the human writing six out of eight times.

Without a 100% accurate AI detection tool, schools may have to implement other strategies to keep students from cheating. Patrick Fan, the Tippie Excellence Chair in Business Analytics at the University of Iowa, details one possible approach.

“I think we need to try to educate students,” Fan said. “What is the purpose for [students] to go to high school to learn to write? You want to know how to write properly, how to communicate, how to better position yourself for college studies. And if [students] say, ‘I’m gonna use ChatGPT to finish all my assignments,’ I think that’s gonna be a wrong attitude.”

Hourcade thinks that ChatGPT can be helpful during brainstorming.

“It can be a really useful tool to partner with,” Hourcade said. “And I think its greatest potential [in] education is if you use it as a tool to give you ideas … to help you get started with something.”

Ajax, however, believes many students won’t be convinced to limit their ChatGPT usage.

“If [teachers] try to say, ‘Just use it for an outline,’ you don’t know if students are going to follow that,” Ajax said. “If we could get a version of [ChatGPT] that will just answer your questions about outlining and brainstorming … it would be one of the best learning tools they could [make] for students.”

Various people and organizations are looking to expand on AI’s educational benefits.

Along with three other University of Iowa researchers involved in AI, Demir published a research paper in February designing an AI teaching assistant to use at the University. Using GPT-3 technology, the teaching assistant system would answer course-specific questions and provide services such as summarizing readings and explaining classroom material, much like a study partner.

“It could potentially use student information, like their grades and their exams and work,” Demir said. “[We] don’t need to worry about [students] asking [instructors] the same questions five times in different ways. TAs can spend more quality time with students and provide more advanced support rather than simple basic questions.”

Similar to Demir’s teaching assistant, Khan Academy announced in March that it would pilot “Khanmigo,” an experimental AI guide that mimics one-on-one tutoring using GPT-4 technology.

Taking advantage of AI’s educational benefits requires knowing how to use the tools. According to ICCSD Director of Technology & Innovation Adam Kurth, courses specifically focused on AI are already being designed at the high school level.

“Implementing coursework in this area makes a lot of sense,” Kurth said. “I think that ultimately, one of the things that we need to do is work with teachers to develop new approaches to education in AI in today’s world, that acknowledge AI and even leverage it where appropriate.”

Hourcade believes computer literacy courses should also be a regular part of education.

“I think computer literacy — to understand how the systems work, even just how data gets collected from you, all the time — will be important for people to know,” Hourcade said. “We’re not [all] going to be computer science majors, [but] I would make [computer literacy] a requirement at the high school [level].”

The education system’s expansion of technology-specific courses could address the issue of digital equity, the ability of individuals to fully participate in society, democracy and the economy by having sufficient information and technological ability, as defined by the National Digital Inclusion Alliance.

Hourcade believes government intervention may be necessary to prevent further exacerbation of digital inequity due to the expansion of AI.

“Some folks [who are] better informed and better educated are the ones who are going to likely benefit more from these systems because they’re aware of how they work … Who’s going to get hurt the most is likely going to be people with lower levels of education or socioeconomic status,” Hourcade said. “That’s where you need some government to step in and provide some level of guardrails.”

Ajax sees this digital divide reflected in the classroom.

“It’s not even the students who are struggling in the classes; it’s more so the students who are doing well who just want an easier way of maintaining their grade,” Ajax said.

However, ChatGPT could also help non-native language speakers and people with disabilities. With its language-processing abilities, the software could allow those with learning disabilities or speech or literacy impairments to communicate more effectively by turning almost any input into a more sophisticated output. Additionally, students who receive course content in an unfamiliar language are able to easily translate and simplify the content into their native language, bridging the language barrier.

Fan holds that ChatGPT’s overall potential as a learning tool will naturally close gaps in education.

“[We can] use ChatGPT as a companion tool to help the students in [disadvantaged] situations to learn to improve on their curriculum,” Fan said. “[We can] help guide the students [to do] a better job in the pedagogy in the learning process.”

Boylan intends to continue addressing equity through his process-focused teaching philosophy.

“Someone who [is] tech-savvy in high school would have been able to use [ChatGPT] and gotten a really good grade on [an assignment],” Boylan said. “I think that [it’s] a lot more equitable to create productive struggle for every student than it is to be outcome-focused.”

Automated industry

The educational landscape isn’t the only thing ChatGPT is changing. As AI strengthens its ability to perform human tasks and as technology, like ChatGPT, becomes increasingly accessible, the classic trope of advanced robots taking over human jobs doesn’t seem too far from reality.

According to Business Insider, jobs in the tech, media, legal and financial industries are at the greatest risk of being replaced by ChatGPT due to companies’ monetary incentives. A Goldman Sachs report from March predicts that, due to generative AI, about 300 million full-time jobs could be exposed to automation.

“Instead of 10 people working on some repetitive stuff, now I can just hire one person, and then leverage AI to do the jobs and allocate the resources towards other [areas],” Fan said. “To me, that’s a better use of the money and the resources for the business advantage.”

By analyzing past programming inputs, AI can act as a software engineer and write code, perhaps putting software engineering at the forefront of affected jobs. Prospective computer science major Zach Buchholz ’23 uses ChatGPT to help with foundational programming.

“Just for fun, I asked [ChatGPT] to make a used car website and it just gave the most basic boilerplate thing,” Buchholz said. “I use [ChatGPT] as a better Google.”

Buchholz believes ChatGPT’s utility decreases with complex projects.

“[ChatGPT] will get close to doing full projects, but I think it’s going to have a hard time integrating parts together,” Buchholz said. “If you tell ChatGPT to do something big, it’s just going to do the simplest version … whereas humans would think about the different parts that go into it and collaborate on it.”

In addition to advanced programming, Fan believes that some jobs are protected from the impacts of AI.

“There’s a list of fields that could be impacted by ChatGPT. On the other side of the spectrum, some fields are not going to be affected by ChatGPT. So, what is the key difference between these two boundaries — the two pillars of the fields?” Fan said. “If you have a lot of … human creativity involved, we doubt that ChatGPT is gonna replace that dramatically.”

Additionally, Ashwini Karandikar, entrepreneurial executive and board member, feels that the possibility of inaccuracy requires humans to be cautious when looking at the output.

“[We need] more fact-checking, more validation or more human checking. And in my work, we already do that extensively,” Karandikar said. “[ChatGPT] is spitting out stuff based on what it has learned, so the person reading it needs to know and be able to decipher right from wrong.”

Additionally, bias in the workplace — already a current issue — may be exacerbated by technology like ChatGPT.

“I think we need to watch out for anything that is generative to really sift through any underlying bias overall. Also, the bias getting into the system really has to be accounted for and actively corrected so that the information that we put out is not only accurate, but it actually makes sense,” Karandikar said.

As a professor and researcher, Demir adds that ChatGPT and other AI tools can help humans make great leaps in the scientific research process.

“I expect significant advancements in science,” Demir said. “Both students and faculty [can] work on more quality research rather than repetitive activities [like] data collection, analysis and basic stuff, which could take weeks or months. The student can do that work potentially in hours or maybe minutes with these AI systems.”

In addition to revolutionizing the research process, learning how to work with ChatGPT could create a stronger workforce.

“It’s less about taking the job away and more about becoming smarter at that job,” Karandikar said. “I think ChatGPT is probably just the first of many, many such developments that we want to see and it definitely has a promise of making all of us smarter.”

Demir holds that while ChatGPT marks a new transition in the intersection of technology and human interaction, it has the potential to be used as a safe and beneficiary tool if approached with the right mindset.

“I think we should be leveraging these tools for our work, for our life and many other aspects. We just need to accept and then potentially benefit from this, rather than being afraid,” Demir said. “It’s [a] transition process and [a] new era for us.”