Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Uprooted

The stories of foreign students finding a new home in the United States.

October 18, 2017

After being born in Sudan and traveling to Egypt, Aibeer Mohamed and her family found themselves looking to the United States for better healthcare services.

Aibeer Mohamed ’19

After being born in Sudan and traveling to Egypt, Aibeer Mohamed and her family found themselves looking to the United States for better healthcare services.

Depression, racism and abuse are only a few of the challenges that junior Aibeer Mohamed has dealt with and overcome before making it to West High.

Born in Sudan to a Fur father and Sudanese Arab mother, Mohamed was often the target of racist comments due to her mixed race and darker complexion than her classmates. One such instance was when Mohamed was in kindergarten, sharing food with her friends. Asking Mohamed’s classmates why they would share food with a “dirty child” like Mohamed, the teacher proceeded to beat Mohamed’s back, severely bruising her.

Outside of uncontrollable factors like her skin tone and race, Mohamed also faced abuse when she refused to wear a hijab at her strict school.

“I don’t think that it’s right for me to have to wear stuff I don’t want to wear. When I was at that age … nobody cared about what I wore, but in school you had to wear a scarf … If you didn’t, you [would] get beaten,” Mohamed said. “I used to fight with the teacher a lot.”

Eventually, Mohamed’s father saw the bruises, leading him to confront the teacher. But this protection didn’t solve the harassment Mohamed dealt with at school, let alone all of the other issues her family had to deal with.

On top of the violent school environment Mohamed faced, many of her relatives lived near Darfur, an area affected by genocide. Although Mohamed was isolated from the violence by living in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, she couldn’t escape the poverty and familial issues that wore her down from day to day.

Having four older brothers, Mohamed is the youngest of five siblings. One of her brothers, Alaeldin, was born with sickle cell anemia and a hole in his heart. These life-threatening birth defects came about because of unhealthy environment Mohamed’s family lived in––due to their poverty, Mohamed’s mother lived in a very dirty area when she was pregnant. Despite her age, the responsibility of caring for her older brother fell upon Mohamed, as her mother had to work long and hard hours to simply provide the bare necessities to her family.

On top of caring for her brother’s health, Mohamed herself struggled with the amount of dust and pollution in Khartoum, the lack of resources, the beatings and the discrimination. All of these factors, combined with the lack of stable economic opportunities in Sudan, contributed to her family’s decision to move to Egypt.

But in Egypt, things only got worse.

By then, Mohamed was fed up with the lack of support from her mother. With her strenuous family circumstances, she even recalls a time when her mother told her she would never forgive Mohamed if she got sick in Egypt. As all these tensions built up, Mohamed was diagnosed with depression.

“As a child you need someone to hang out with and play with. For me, every day we’d have a new problem. Like my brother is sick and mom would focus all of her attention on [him]. I needed attention too,” Mohamed said. “When you keep stuff to yourself … you feel self-conscious. You think to yourself, ‘What’d I do, should I kill myself? I want to kill myself.’”

Beyond her family needs, the Egyptians in her community also had a taxing effect on Mohamed’s feelings. She recalls being scared to go outside to play soccer because the men would always verbally and sexually assault young girls. Other instances, such as simply calling her light-skinned mother “Mom” in public triggered some Egyptians to question their relationship and even to look down on Mohamed, given her dark complexion. Another time, a boy randomly slapped her uncle, causing an altercation between Mohamed and the boy’s family. In any case, all of these daily challenges contributed to her depression.

Adding to the situation, Alaeldin’s condition wasn’t improving. Consequently, Mohamed’s family went to the United Nations to apply to come to the United States and help treat his continuing sickness.

When news of their acceptance came, Mohamed was ecstatic.

“I was shocked. I couldn’t believe it. I thought the US was like what you watched on TV,” Mohamed said.

Mohamed’s family’s dream was starting to come true as they moved to Georgia: Alaeldin finally had the opportunity to receive proper medical attention. But that didn’t equate to instant happiness for Mohamed herself. Mohamed still had to take care of Alaeldin and regularly took him to the hospital. In addition, Mohamed’s mother initially didn’t allow her children to interact with Americans, making it harder for Mohamed to make friends which furthered her depression.

“We didn’t know anybody … and my mom was kind of scared,” Mohamed said. “She didn’t let us go outside. … We just stared out the window, and I wanted to go play and interact with other kids.”

Eventually, Mohamed’s other brother, Sharif, caught on to her depression and started to give her the support she needed.

“He did everything for me, even when I was sick he’d take care of me, give me food, make sure that I’m okay, help me with my homeworkㅡbasically what moms do for their kids,” Mohamed said. “I look up to him, he’s my inspiration … He helped me overcome my depression.”

After defeating her depression, Mohamed’s family moved to Iowa where they began a new chapter of life. Now Mohamed plays on West’s soccer team and even has aspirations to play basketball.

However, one problem remains for Mohamed in America: racism. So while America has been a means of improving the health of Mohamed’s brother, some things just haven’t changed wherever Mohamed has lived.

“[America is] good because you have more opportunities. You go to school, you have the freedom to wear anything that you want you have a car, you have good food,” Mohamed said. “But for me I don’t think America is good … It’s just fast. Too fast. And racism is too much, there’s too much going on.”

These feelings have determined what Mohamed wants to do next. For her, moving back to Sudan to meet with her father again and to avoid the racism in the United States is the best option, despite knowing the poor social conditions in Sudan from her past experiences.

“Women don’t have the right to do [a] bunch of stuff,” Mohamed said. “They treat the man as the king or the owner of the women, so I want to change that.”

Despite Nidhi Patel’s initial struggles with adapting to the new language and culture of the United States, she remains steadfast in her pursuit of a better education.

Nidhi Patel ’19

Despite Nidhi Patel’s initial struggles with adapting to the new language and culture of the United States, she remains steadfast in her pursuit of a better education.

When she saw a woman smoking a cigarette, she immediately started to cry.

“When I landed in the California airport, I saw a lady that was taking a cigarette,” said Nidhi Patel ’19. “I just wanted to go back.”

Having just moved from India, Patel wasn’t used to seeing women freely smoke cigarettes in public, so her first impression of the United States wasn’t very welcoming. This cultural transition from India to America took quite a while to adjust to.

Patel moved from India to the United States in 2016. Her extended family of 14 had a system through which the grandparents would work in the United States and then transfer some of their money to the rest of the family in India. This left the whole family in a prosperous state for many years, but that eventually started to change. That process slowed down with the decline of her grandparents’ health. Needing support in the United States, Patel’s grandparents asked the rest of the family to move to the United States.

This led Patel’s family to California and to the culture shock they felt as immigrants in a new country. Sights seemingly mundane like a woman smoking a cigarette represented the discomfort Patel and her family were feeling just minutes after landing in the United States. Although they had to leave her grandparents after just one week in search of economic opportunities, Patel tries to remain positive, specifically enjoying the close-knit Indian community in Iowa City.

Despite the welcoming Indian community, transitioning into West High’s school community and a vastly different education system remains a tiresome endeavor.

“I never ask questions in class because I’m always scared that [I’ll] mispronounce something,” Patel said.

Luckily, Patel found the support she needed in teachers such as Maureen Head. Giving Patel advice throughout the year, Head has been a key source of guidance and inspiration for Nidhi.

“I think sometimes for a student learning English, she got discouraged,” Head said. “No student wants to feel like they don’t understand.”

Instead of simply reiterating lessons to Patel, Head made an effort to meet with her before school each morning, developing a personal connection with Patel and motivating her academic endeavors.

“[Maureen Head] always gives me positive things–that I have to be strong and I have to ask questions in class,” Patel said.

In the end, this system of support paid off.

“She worked extremely hard,” Head said. “[Now] she’s really excited and really positive … She kind of hit her stride and [is] not afraid to ask for help—she’s grown a lot.”

While fitting into the American education hasn’t been easy, it’s been a worthwhile effort. In India, Patel was strongly against many of the principles that guided the education system. For example, Patel was always used to thinking in only one vein of logic: to always listen to the teacher.

One especially memorable teaching was the importance of the first impression, lending itself to Patel’s initial shock seeing the cigarette-smoker. In India, a positive first impression usually means being the brightest student in the class. Being considered bright was especially advantageous in Patel’s hometown of Vadodara.

“In India, if you are intelligent, then the teacher treats you very special,” Patel said. “[Otherwise,] they think [students] are so bad.”

For example, Patel recalls one instance in which her bright friend was permitted to decide whether or not the class had to do homework that night. At West, however, Patel feels more an equal part of the classroom community, even given her trepidation for speaking up and asking questions. And like almost everyone else in the classroom, Patel has always had a hobby to get away from schooltime stress.

“My bicycle has been my best friend,” Patel said. “Wherever I want to go, [I] go with a bicycle.”

In Iowa, with longer commuting distances and busy hours for her parents, Patel has fewer opportunities to practice her favorite pastime. Moreover, Patel chooses not to bike as much anymore in order to focus more on education and to fulfill her parent’s dream of her receiving a college education.

In traversing halfway across the globe, Patel and her family have faced many hardships, setbacks and unexpected changes to their plans. But what has made it all possible has been her parents’ strong work ethic and dream to send their daughter to college. Given her perseverance throughout high school, Patel shares her parents’ determination.

“I [want to] change myself. To get involved in everything, to talk to everybody,” she said. “I’m trying my best. That’s it.”

Lifelong friends Merci Sikitu and Linda Adela have overcome immense challenges from across the world ever since they were infants.

Linda Adela ’20 and Merci Sikitu ’19

Lifelong friends Merci Sikitu and Linda Adela have overcome immense challenges from across the world ever since they were infants.

For many, having to flee a war-stricken world characterized by witchcraft and destitution would be considered a nightmare. For Merci Sikitu ’19 and Linda Adela ’20, it was reality.

Both girls were born in the Democratic Republic of the Congo during the Second Congo War, a violent conflict that displaced over two million Africans. When Sikitu and Adela were infants, their parents fled the country to provide safer lives for their families. They traveled in a group by foot, then by boat, from Kinshasa, the capital of the DRC, to Zambia.

“When we moved to Zambia … it was hard because the people spoke another language,” Sikitu said. “We didn’t know many people, and there wasn’t a lot of food. It was a struggle in the beginning because the people there would look at you like you were a type of different creature.”

Because of the isolation they faced, the girls’ families sought a better life elsewhere. After moving from country to country, the girls settled in Zimbabwe where they spent their primary years. Although life in Zimbabwe was an improvement, the country still didn’t have the stable jobs their families needed to survive. Because of this, Sikitu and Adela’s fathers found work in South Africa, where jobs were more plentiful.

However, these jobs came with a price: risking their lives. Armed robbers stopped the buses their fathers traveled on and threatened to kill everyone inside if they didn’t give up their wages. Their parents told them stories about what happened during these situations.

“This one woman, she had a baby … and she said, ‘I don’t have money,’ but she was hiding money so she could buy the baby food on the ride,” Sikitu said. “[The thieves] came and searched her. When they found the money, they shot the mom. The baby started crying, so they shot the baby too.”

Travel was difficult for the girls as well. Sikitu and Adela walked long distances from their refugee camp to their Zimbabwean school. This seemingly simple journey was made dangerous by threats of being bitten by snakes, trampled by elephants or chased by potential rapists.

“These Zimbabwean guys who were drunk would start chasing girls and [would try] to rape them,” Sikitu said. “We would just see them and start running … It was very scary in the moment … They would chase you, and whichever person they would catch, they would go in the bushes and rape them. The school [would] not care because they’re used to it.”

School itself was tough because of the physical and emotional abuse in Zimbabwean schools. Refugee students like Sikitu and Adela would receive more beatings for more trivial matters than Zimbabwean students, increasing the animosity between Zimbabweans and foreigners.

“I used to just cry on the desk,” Sikitu said. “[The teachers] would say, ‘Wake up and do your work’ … And you feel like you just want to stand up, get out of that chair and leave. But you cannot walk out because [the teachers] follow you and you would get more whoopings.”

Their parents knew that life in Africa was not optimal for their children’s success and dreamt of coming to the United States. Eventually, this dream became reality when their visas were granted. The girls were ecstatic.

“In Africa, when they said we [were] going to America, I [thought] it was like heaven,” Adela said. “Big houses, cars, everything.”

However, life in the United States was not what Sikitu and Adela expected.

“They gave us a house [where] the restroom was bad… We did not have a car or anything,” Sikitu said. “So we’re just like, ‘Where are we?’ because I thought America would be [different], like I didn’t see money on the floor.”

Because the girls came to the US at different times, Adela went to Texas and Sikitu was sent to Alabama. Months after Adela moved, she relocated once again because her parents had difficulty finding jobs. They came to Iowa and lived in Cedar Rapids for six years before coming to Iowa City.

Sikitu, however, stayed in Alabama. Life was difficult there because she did not understand the students and felt isolated by her peers for being different. Her classmates would make fun of her short hair, required in Zimbabwean schools, or say she used to live with animals.

“What I went through at school was harsh,” she said. “It’s hard [being] without family members. Nobody [understands] your pain. You don’t know how to express your feelings because you don’t know the language. You don’t know what’s happening, so you just cry and cry. You wish you were dead. I started wishing I was back in Africa because I’d rather struggle than be with these people here, calling me names and making me feel bad about who I am.”

After Sikitu finished middle school, Adela’s family encouraged Sikitu’s family to move to Iowa City, where she was met by a more welcoming, less discriminatory environment.

“[In Iowa City], there’s not as much racist people. They respect who you are. They respect your ideas. They respect what you do,” Sikitu said.

The positive community and supportive teachers enabled the girls to improve their schooling. Now that they are both receiving better educations in Iowa City, their parents encourage them to work hard in school and take advantage of the opportunities they never had.

“In Africa, they always call and say, ‘We need money.’ My mom just sent $200 so she can pay the house bill,” Adela said. “[My dad] tells us, ‘This is why we encourage you to focus on school and stay in school and do good, so you can come and help the family.’”

One thing the girls had to leave behind when they came to the United States was their family and friends. Adela misses her grandmother that still lives in Zambia today.

“My grandma and I are really close,” Adela said. “[When] my mom would go to school, my grandma would stay with me [and] feed me. If there [wasn’t] enough food in the house, she would tell the older people, ‘You guys are not eating today, save the food for the baby.’ Everywhere she [went], I would always be with her. I miss her.”

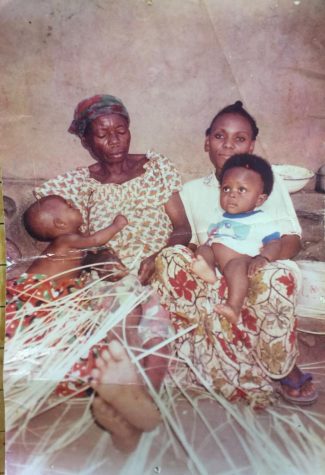

Pictured in the Congo, Sikitu and her mother (right) sit with her grandmother and cousin.

Despite this, a positive change for the girls when they came to the United States was the enhanced security. Back in Africa, resources taken for granted here, like police officers or hospitals, were often corrupt. As a result, bribery was necessary for basic safety or health needs to be taken care of.

“[The best thing about the US is] they have security and a lot of police officers,” Sikitu said. “[In Africa], the ambulance arrives late, and the way they solve their cases here and there is very different. Here, they take care of it and they make sure they find the solution. But there, if you’re not that important [of a] person, it’s like you’re nothing.”

While the girls want to return to Africa, they do not want to visit Zimbabwe because of “witchcraft” in the country. A Gallup poll showed that around 55 percent of sub-Saharan Africans believe in dark spiritual magic, which has led to Africans being murdered on the basis of them being witches.

“I want to have a job, get a lot of money, then go back to Africa and help people,” Adela said. “But I will not go back to Zimbabwe because… there’s a lot of witchcraft … [and] a lot of people that will go there and not come back.”

Even though the two miss their extended family in Africa, having each other is a source of comfort and support.

“We have memories together,” Sikitu said. “When I [talk] about something, she already knows what I’m talking about. But if it was a different person, they would not know what we’ve been through.”

Ms. Haina • Feb 28, 2018 at 3:32 pm

Please add Prateek and Shawn to that list of talented student reporters.

Ms. Haina • Feb 28, 2018 at 3:31 pm

What a wonderful example of student feature writing! Great job, Anjali and Jessica, of identifying a topic of interest, narrowing the angle, telling the story, and selecting and incorporating direct quotes for the best impact. Keep up the hard work!