Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Linda Adela ’20 and Merci Sikitu ’19

October 25, 2017

Lifelong friends Merci Sikitu and Linda Adela have overcome immense challenges from across the world ever since they were infants.

Lifelong friends Merci Sikitu and Linda Adela have overcome immense challenges from across the world ever since they were infants.

For many, having to flee a war-stricken world characterized by witchcraft and destitution would be considered a nightmare. For Merci Sikitu ’19 and Linda Adela ’20, it was reality.

Both girls were born in the Democratic Republic of the Congo during the Second Congo War, a violent conflict that displaced over two million Africans. When Sikitu and Adela were infants, their parents fled the country to provide safer lives for their families. They traveled in a group by foot, then by boat, from Kinshasa, the capital of the DRC, to Zambia.

“When we moved to Zambia … it was hard because the people spoke another language,” Sikitu said. “We didn’t know many people, and there wasn’t a lot of food. It was a struggle in the beginning because the people there would look at you like you were a type of different creature.”

Because of the isolation they faced, the girls’ families sought a better life elsewhere. After moving from country to country, the girls settled in Zimbabwe where they spent their primary years. Although life in Zimbabwe was an improvement, the country still didn’t have the stable jobs their families needed to survive. Because of this, Sikitu and Adela’s fathers found work in South Africa, where jobs were more plentiful.

However, these jobs came with a price: risking their lives. Armed robbers stopped the buses their fathers traveled on and threatened to kill everyone inside if they didn’t give up their wages. Their parents told them stories about what happened during these situations.

“This one woman, she had a baby … and she said, ‘I don’t have money,’ but she was hiding money so she could buy the baby food on the ride,” Sikitu said. “[The thieves] came and searched her. When they found the money, they shot the mom. The baby started crying, so they shot the baby too.”

Travel was difficult for the girls as well. Sikitu and Adela walked long distances from their refugee camp to their Zimbabwean school. This seemingly simple journey was made dangerous by threats of being bitten by snakes, trampled by elephants or chased by potential rapists.

“These Zimbabwean guys who were drunk would start chasing girls and [would try] to rape them,” Sikitu said. “We would just see them and start running … It was very scary in the moment … They would chase you, and whichever person they would catch, they would go in the bushes and rape them. The school [would] not care because they’re used to it.”

School itself was tough because of the physical and emotional abuse in Zimbabwean schools. Refugee students like Sikitu and Adela would receive more beatings for more trivial matters than Zimbabwean students, increasing the animosity between Zimbabweans and foreigners.

“I used to just cry on the desk,” Sikitu said. “[The teachers] would say, ‘Wake up and do your work’ … And you feel like you just want to stand up, get out of that chair and leave. But you cannot walk out because [the teachers] follow you and you would get more whoopings.”

Their parents knew that life in Africa was not optimal for their children’s success and dreamt of coming to the United States. Eventually, this dream became reality when their visas were granted. The girls were ecstatic.

“In Africa, when they said we [were] going to America, I [thought] it was like heaven,” Adela said. “Big houses, cars, everything.”

However, life in the United States was not what Sikitu and Adela expected.

“They gave us a house [where] the restroom was bad… We did not have a car or anything,” Sikitu said. “So we’re just like, ‘Where are we?’ because I thought America would be [different], like I didn’t see money on the floor.”

They gave us a house [where] the restroom was bad… We did not have a car or anything. So we’re just like, ‘Where are we?’ because I thought America would be [different], like I didn’t see money on the floor.

— Merci Sikitu

Because the girls came to the US at different times, Adela went to Texas and Sikitu was sent to Alabama. Months after Adela moved, she relocated once again because her parents had difficulty finding jobs. They came to Iowa and lived in Cedar Rapids for six years before coming to Iowa City.

Sikitu, however, stayed in Alabama. Life was difficult there because she did not understand the students and felt isolated by her peers for being different. Her classmates would make fun of her short hair, required in Zimbabwean schools, or say she used to live with animals.

“What I went through at school was harsh,” she said. “It’s hard [being] without family members. Nobody [understands] your pain. You don’t know how to express your feelings because you don’t know the language. You don’t know what’s happening, so you just cry and cry. You wish you were dead. I started wishing I was back in Africa because I’d rather struggle than be with these people here, calling me names and making me feel bad about who I am.”

After Sikitu finished middle school, Adela’s family encouraged Sikitu’s family to move to Iowa City, where she was met by a more welcoming, less discriminatory environment.

“[In Iowa City], there’s not as much racist people. They respect who you are. They respect your ideas. They respect what you do,” Sikitu said.

The positive community and supportive teachers enabled the girls to improve their schooling. Now that they are both receiving better educations in Iowa City, their parents encourage them to work hard in school and take advantage of the opportunities they never had.

“In Africa, they always call and say, ‘We need money.’ My mom just sent $200 so she can pay the house bill,” Adela said. “[My dad] tells us, ‘This is why we encourage you to focus on school and stay in school and do good, so you can come and help the family.’”

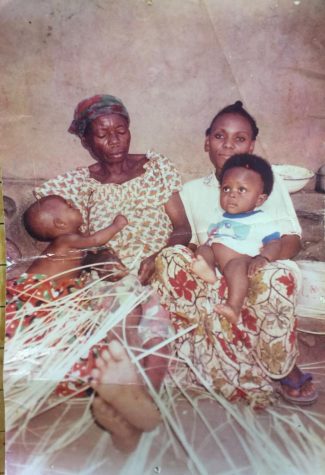

One thing the girls had to leave behind when they came to the United States was their family and friends. Adela misses her grandmother that still lives in Zambia today.

“My grandma and I are really close,” Adela said. “[When] my mom would go to school, my grandma would stay with me [and] feed me. If there [wasn’t] enough food in the house, she would tell the older people, ‘You guys are not eating today, save the food for the baby.’ Everywhere she [went], I would always be with her. I miss her.”

Pictured in the Congo, Sikitu and her mother (right) sit with her grandmother and cousin.

Despite this, a positive change for the girls when they came to the United States was the enhanced security. Back in Africa, resources taken for granted here, like police officers or hospitals, were often corrupt. As a result, bribery was necessary for basic safety or health needs to be taken care of.

“[The best thing about the US is] they have security and a lot of police officers,” Sikitu said. “[In Africa], the ambulance arrives late, and the way they solve their cases here and there is very different. Here, they take care of it and they make sure they find the solution. But there, if you’re not that important [of a] person, it’s like you’re nothing.”

While the girls want to return to Africa, they do not want to visit Zimbabwe because of “witchcraft” in the country. A Gallup poll showed that around 55 percent of sub-Saharan Africans believe in dark spiritual magic, which has led to Africans being murdered on the basis of them being witches.

“I want to have a job, get a lot of money, then go back to Africa and help people,” Adela said. “But I will not go back to Zimbabwe because… there’s a lot of witchcraft … [and] a lot of people that will go there and not come back.”

Even though the two miss their extended family in Africa, having each other is a source of comfort and support.

“We have memories together,” Sikitu said. “When I [talk] about something, she already knows what I’m talking about. But if it was a different person, they would not know what we’ve been through.”