Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Alone

Throughout the ICCSD, spaces have been designated to isolate students from their peers when faculty felt their behavior was uncontrollable. However, improper use of these areas led the district to call for their removal by the beginning of the 2018-19 school year.

December 22, 2017

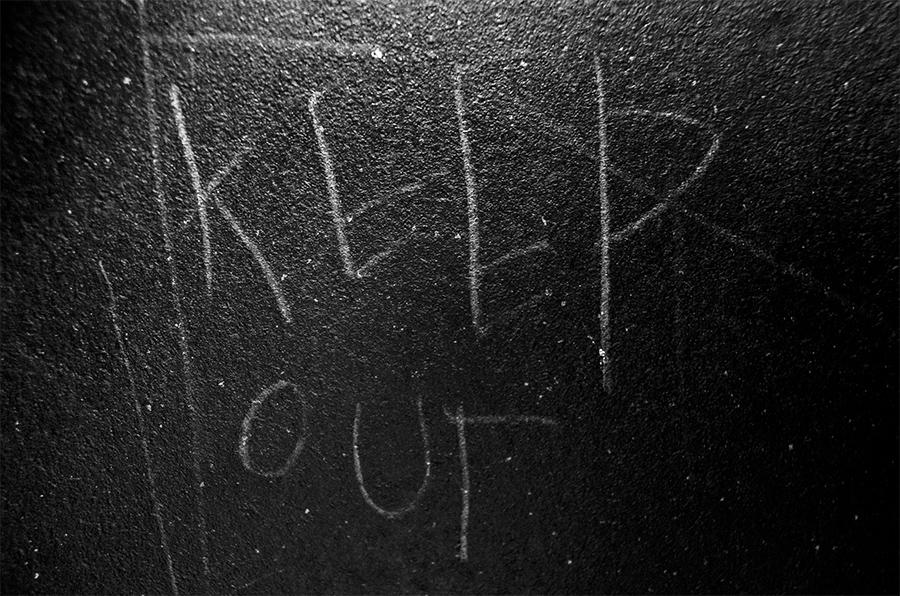

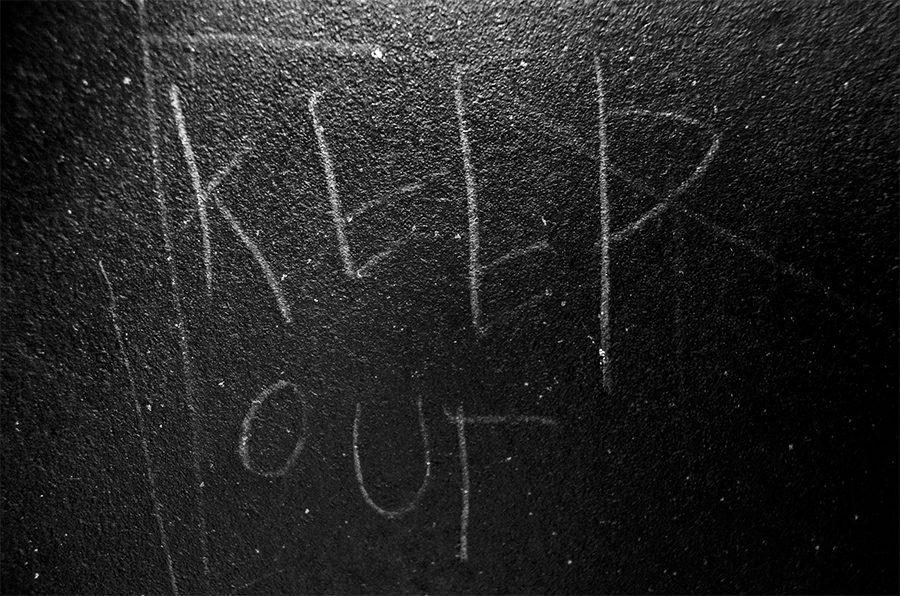

An eight-year-old child sits alone in a dark space with only a small window of light and no way to leave. Messages reading “KEEP OUT” and traces of vomit line the interior. They bang on the walls, but the room is soundproof, so their pleas are left unheard. Contrary to what one might think, this isn’t a juvenile detention center.

It’s a room in a public elementary school.

This space, called a seclusion room, is one method of dealing with students who are considered to have behavioral issues. A 2011-12 report by National Public Radio stated that children were placed in seclusion rooms about 104,000 times in that school year nationwide. Until recently, seclusion rooms were commonly used throughout the ICCSD as well.

“We have had some temporary rooms that have been created in order to keep kids safe from themselves,” said Superintendent Steve Murley. “Those are part of an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) process that goes through special education … Iowa law says that you can seclude students in order to keep them safe or keep their peers safe, and they don’t have to be special [education] kids in order to be secluded.”

Seclusion rooms, also known as behavioral discipline rooms, are designed to protect students from harming themselves. Each seclusion room in the ICCSD is a roughly 6-foot by 6-foot wooden box with padding, one single window of light and no handle on the door from the inside.

These spaces are intended to help students with behavioral disabilities that have specific IEP plans: strategies developed by parents in correlation with the school on how to react in an instance where their child acts out. If a student does not have an IEP, these spaces are intended to be used only in severe circumstances, like if a student is physically assaulting another student.

However, the Iowa Department of Education found that around 4 percent of seclusions in the ICCSD during the 2015-16 school year were for minor infractions like stepping out of line at recess or talking back to a teacher. During this investigation, it was found that schools were misusing these rooms, not only by utilizing them in the wrong situations but also by leaving students in there for longer than the maximum time of around 50 minutes. Additionally, in some instances faculty did not correctly document incidents involving seclusion.

One student placed in a seclusion room in multiple instances during elementary school is Davonte Levy ’18, who vividly remembers the first time he experienced this form of disciplinary action.

“I was probably in fifth grade when I got sent [to a seclusion room] for the very first time, and I hated it,” Levy said. “They pushed me in there and shut the door and locked it. You can’t open it from the inside. They’ll block the door … It felt like I was in prison. Kids punched the door and [were] angry. They wouldn’t let you back out until you said something that pleased them.”

Sitting in the 6-foot by 6-foot seclusion room, Levy recalls the discomfort he felt from the foul smells, limited space and suffocating heat he had to endure.

Levy believes that being secluded did not have a positive effect on his behavior; instead, it negatively affected his learning experience.

“I’m still mad about the [seclusion] room because it ruined part of elementary school. It took the [experience] away,” Levy said. ”I think it made things a lot worse for the kids. Sitting in the dark didn’t help kids calm down.”

Jillian Baker ’19 is another student that was isolated in elementary school for talking back to her teachers. According to Baker, rooms in which students are isolated from their peers did not stop unruly behavior, but instead made the students feel like they were being branded as troublemakers.

“[Being secluded] didn’t necessarily make me think about what I did—if anything, it just made me more upset and made me feel more isolated,” Baker said. “[It] made me feel like I was weird, and I don’t think it changed my behavior at all because even after I got out, I’d still end up back in [the seclusion room.]”

Because many seclusions occur when children are young, forms of discipline like this have the potential to affect the psychological health of students later on in life, especially if seclusion is recurring. During the 2015-16 school year, 277 out of 455 incidents where seclusion rooms were used, or 61 percent, were for kids between pre-kindergarten and third grade.

According to Dr. Megan Foley Nicpon, a psychology professor at the University of Iowa, isolating students for their behavior at a young age may send negative messages about who they are as people rather than the decisions they make.

“There’s a lot of data to show that students with behavioral problems have more depression, anxiety, lower self-concept and you have to think that it’s probably related to the messages that they’re receiving,” Foley Nicpon said. “It’s kind of a chicken and the egg sort of thing. Are they acting out because they’re told these awful things about themselves, or are they told these awful things about themselves because of their behavior? It’s cyclical, and so how do you break that cycle with kids?”

Because of this, Foley Nicpon believes that students’ poor classroom behavior could continue into junior high and high school. Memories associated with strong emotions are more vivid and memorable in young children; this results in emotional memories continuing to affect later behavior for long periods of time following the traumatic event.

Baker believes that her behavior would not have carried on had it not been for labels given to her as an elementary student.

“When teachers isolate you and label you as one thing regarding behavioral issues, or anything in general, you tend to gravitate towards the people that have the same label as you,” Baker said. “[This] is why my behavioral issues continued into eighth grade when they shouldn’t have at all.”

Baker views this labeling as harmful to students that may not be able to control their behavior. She believes that it interferes with their education and prioritizes other students’ learning over the mental well-being of those placed in seclusion.

“I do think an institution exists [that] puts kids who have behavioral issues, whether they are intelligent or not, at a disadvantage,” Baker said. “When you label somebody as a troublemaker, that gets in the way of their academic achievements … I don’t think that [teachers and administration] didn’t care about me, but I don’t think that they solved my behavioral problems in the way that would have put my interests first.”

Furthermore, students that were placed in seclusion rooms faced social isolation as well. Students sent to these rooms on multiple occasions felt alienated by their peers. This had negative effects on students’ perceptions of themselves.

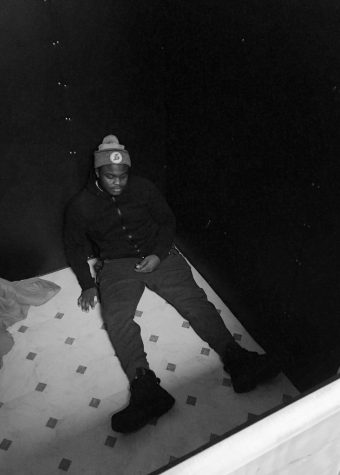

Levy looks through the single window of a seclusion room from the outside. While this particular seclusion room is better lit, Levy recalls that the room he was secluded in at Kirkwood Elementary would often be pitch black due to a curtain covering the window.

“People didn’t want to be around you because they think, ‘You’re always mad … You’re always in the [seclusion] room, so why do you want to talk to us or want to hang out with us?’ I think that set a label on a kid and a person because everybody’s scared. They think, ‘I don’t want them to hurt me because they have been in the [seclusion] room,’” Levy said.

Baker also felt that being secluded impeded her abilities to make friends and view herself in a positive manner.

“Whenever I didn’t have problems with authority and I tried to make conversation with my teachers or I tried to initiate friendships, that didn’t happen,” Baker said. “I feel like whenever something didn’t work out the way it should have, I related it back to me just not being able to act right, and I remember being really upset about that because I couldn’t figure out how to act right.”

Misconduct with seclusion in the district eventually caught widespread media attention and was featured in USA Today -over the summer. Soon after, the American Civil Liberties Union spoke out against isolating students and called on Iowa to change its restraint and seclusion policies.

In a news release, Daniel Zeno, the policy counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union of Iowa said, “Iowa must update its rules to reflect growing consensus that seclusion and restraints should not be used to discipline or punish children. Children should only be subjected to these practices in emergencies and when there are no other alternatives.”

Following a complaint filed from the Department of Education and backlash from parents, the ICCSD began to change its use of seclusion. The district hopes to prevent future misuse of these rooms by removing them altogether, or, if this is not possible, repurposing them by the beginning of the 2018-19 school year.

“As a district, we weren’t meeting the standard of care that we should when it came to seclusion,” said ICCSD School Board Member Ruthina Malone. “It was mainly based on the Department of Education’s report [that] a lot of the findings that were listed in there [were] that we were delinquent in the way we were handling a lot of our cases.”

However, the audit of seclusion rooms has led to another problem: what to do with special education students that had IEPs that depended on these rooms.

According to ICCSD Director of Special Education Lisa Glenn, students with IEPs will continue to have access to seclusion spaces as needed.

“The district will implement all IEPs as written, including those which include a safe seclusion area,” Glenn said. “When needed, the district will work with building staff to find a permanently constructed area for use in implementing the IEPs in the building … The focus of our work continues to be to improve and enhance behavior support for students at all levels, and to design high-quality individual plans for those who need them.”

As the ICCSD makes the shift to adopt new methods of handling misbehaving kids, Murley acknowledges that this may be a rough transition to make because seclusion rooms were formerly the norm within schools across the district.

“This has been in place in the district and in other districts in Iowa for a very long time … It’s not really a gradual change,” Murley said. “We’re going through some learning with this process … We’ll probably experiment with some different kinds of spaces in different schools, and that’ll be a collaborative effort with parents, so whatever safe space we create meets their expectations too.”

Other than auditing seclusion rooms, the ICCSD has taken measures to make sure staff are aware of how to correctly address misbehaving students. Administration has retrained faculty in areas where seclusion rooms are still active to ensure no further misuse occurs.

Additionally, the district is now experimenting with other methods to positively interact with students facing behavioral problems. For example, a room has been placed at Kirkwood Elementary next to the principal’s office with a table and various games to help students calm down.

“Now, instead of putting students in the seclusion room, [staff have] this safe space where they can have the student go in and de-escalate,” Murley said. “There’s room at the table where if [a faculty member] needs to have a conversation with them [or] if the student just needs some room to do their school work without being in proximity to the other kids or whatever was setting them off, they have the room to do that now.”

This method of direct communication, also known as talk therapy, is one strategy that the ICCSD plans to use to replace seclusion. This was previously effective for Baker, who believes that having a supportive adult figure in junior high helped change her views on authority.

“I had a guidance counselor that was there at North Central, and she really helped me with everything,” Baker said. “I took a step back … and realized that I shouldn’t be acting that way and that teachers were not purposefully being authoritarian figures. I learned to appreciate teachers a lot more.”

Levy acknowledges the influence of interaction and reiterates that conversation, instead of seclusion, has the potential to change the entire educational experience of a student.

“I think teachers should talk to kids more. That’s how kids and teachers can get better connections,” Levy said. “You never know how a person’s day can be before they get to school or after school; just interacting with somebody can change everything.”