Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

The cost of excellence

With athletes feeling pressure to excel from a variety of factors, some push themselves to unhealthy limits to succeed.

April 26, 2021

“Where excellence is a tradition” has been a true testament to the West High athletics department for decades. The halls of West are packed with gold trophies and plaques, and state championship banners honoring West’s numerous victories adorn the gym walls. Behind the glory of these achievements are years of devotion and training. As athletes strive to win the next state title, some push themselves to the extreme.

Under pressure

The fine line between an athlete’s best performance and exceeding their limits can be fragile. This rings true for many athletes at West who strive to compete at a top level consistently. For track and cross country runner Ella Woods ’22, the combination of a competitive environment and the pressure to excel causes her to aim for an unrealistic standard.

“I feel like I always have to be good … and I can’t have bad days,” Woods said. “When I win one race, I feel like I have to win them all.”

West High Girls Varsity Tennis Coach Amie Villarini feels athletes have pressure coming in from a multitude of sources to continually achieve the best results.

“Pressure exists because we all want to succeed. We all want to be winners. Nobody wants to fail,” Villarini said. “At West, there are certainly higher standards, which then makes for stronger competition with peers to make the cut or to be the best.”

Like many of her players, Villarini participated in United States Tennis Association junior tournaments and can draw parallels to her personal experiences.

“I remember feeling bad and beating myself up a lot for making mistakes and losing because I was the only one to blame,” Villarini said.

Athletes may also feel the stress of maintaining good time management between work, school and sports. For some, juggling these commitments can make playing a sport feel like a burden.

This is the case for track and cross country athlete Clare Loussaert ’22, who feels the constant expectation of improvement can be exhausting.

“This sport kind of became more of a chore than it was enjoyable,” Loussaert said. “All I wanted to do was get better, and every single thing I needed to do perfectly.”

Bailey Nock ’18, a West High alumni and current collegiate cross country runner at the University of Colorado Boulder, resonates with the effect the competitiveness of West athletics can have on athletes.

“There’s a lot of pressure for high school athletes, especially at West High, because we have this tradition of winning and producing titles,” Nock said. “That just puts a lot of pressure on kids when we’re very young.”

Nock has since discovered that athletes must maintain a healthy balance between striving to do their best and pushing themselves to the limits.

“We all kind of toe this tightrope of [wanting] to be the best. But we often will fall off the tightrope and be injured or mentally we just can’t do it anymore and we burn out,” Nock said. “There’s a lot of times where you want to get right up to that limit, but you don’t ever want to go above it, and toeing that line is extremely difficult.”

Nock feels that athletes must take care of their mental health if they want to succeed.

“I was doing track for everybody besides myself … to make other people happy, and that really takes a toll on your mental health,” Nock said. “I think an athlete is never going to perform as well as they can if they don’t have that support and they don’t believe that they can.”

Girls varsity tennis player Ella DeYoung ’23 echoes these sentiments.

“Mental health is the hardest part of tennis. Most of the time, you’re by yourself, and it is hard to not get in your head,” DeYoung said. “Lots of times you get so in your head that you spiral out of control, and it’s hard to get back from that.”

Nock believes there is a stigma around athletes fighting through mental health issues, which is often overlooked or ignored, especially in men’s athletics.

“Athletes are kind of just told to toughen it up and to figure it out on their own,” Nock said. “Guy athletes I know have struggled with it, but they’re told to ‘man up,’ and that just is not fair to them.”

As a male baseball player, Schuyler Houston ’21 has faced similar experiences regarding this stigma surrounding men’s mental health.

“‘Be a man’ is one of the common phrases that you hear. That’s one of the ones people like to harp on nowadays, which I get. It’s definitely not a positive phrase that helps growth,” Houston said.

Although some athletes find themselves struggling mentally, for DeYoung, it can be reassuring to know that others can relate.

“If you’re struggling with something, there’s always someone else struggling with it as well. So, reach out to someone,” DeYoung said. “I’m sure everyone has struggled with the pressure that athletics bring. Find someone you can trust and reach out for help.”

Despite the mental toll that sports can impose on athletes, Head Football Coach Garrett Hartwig notes how athletics can also be a source of emotional support.

“I have noticed that athletes often use sports and athletics as a form of mental therapy,” Hartwig said. “[It’s] a release from other daily pressures and an opportunity to focus, think, play and have some fun in another venue.”

Pushing the limits

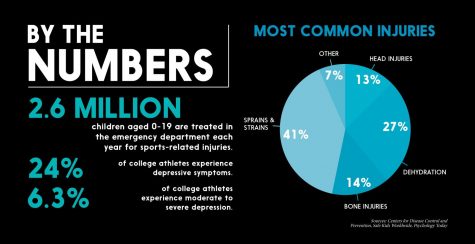

Along with straining mental health, sports can take a large toll on physical health. According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, almost a third of all childhood injuries are sports-related.

Villarini believes much of the physical stress her tennis players face comes from not wanting to let down their teammates.

“I have had players push their bodies to the max because they are extremely competitive and don’t want to let the team down,” Villarini said. “The consequences of making an injury worse and not being able to play are far greater than the consequences of sitting out one match or a practice.”

During her first year on the track and field team, Loussaert suffered injuries which she attributes to exhausting her physical health in a long indoor season.

“Freshman year, I definitely did not know that I was pushing myself to the point of stress fractures because I didn’t know a single person on the team … that wasn’t suffering from shin splints,” Loussaert said.

Along with this physical hardship, Loussaert found it difficult to voice her concerns regarding her stress fractures.

“I was trying to say ‘No, my shins hurt’ and ‘I’ve had stress fractures before’ because I know this feeling, and I know what’s pushing my body too far,” said Loussaert. “But then to hear like, ‘Oh, you can keep pushing through’ … It was really challenging to keep advocating for myself and it made me question myself a lot.”

As a coach, Hartwig believes it is his responsibility to monitor the health and well-being of his athletes.

“Pushing limits is important, but not to the extreme,” Hartwig said. “It’s critical to identify the ‘breaking point,’ and I feel my coaching staff and I have a decent handle on this, but it is always a concern.”

Girls Varsity Track Coach Mike Parker believes the best way health can be monitored is through two-sided communication.

“There is one thing that will help a program year after year,” he said. “Figure out a way to get student-athletes to communicate to [coaches] and [coaches] to communicate with them.”

While injuries are tough on athletes, many have found ways to make the most of it. Erica Buettner ’21 found positive ways to channel her energy during recovery.

Buettner’s hip injury originally began as a dull pain that didn’t improve with stretching and ice. As her injury progressed, Buettner found it hard to not be able to directly contribute to the team’s successes. However, the extra time allowed her to pick up hobbies she previously did not have time for.

“I realized that I needed more balance in my life because running was such a big part of my identity,” Buettner said.

Nock agrees that while not competing alongside teammates can be frustrating, it can allow athletes to gain more appreciation for their sport.

“Mentally, it’s really hard to be injured, because you put in all this work and then your body gives up on itself,” Nock said. “The one good thing about injuries is that when you’re not doing the sport and when you have to sit on the sidelines, you start to realize how much you miss it.”

To prevent future injuries, Buettner has implemented some new techniques into her training routine by gradually building up in mileage when she starts running, and maintaining consistent sleep and stretching schedule.

West High Athletic Trainer Sheila Stiles notes that rest is one of the most essential components to ensure athletic success during the season.“Our bodies start to break down when we do repeated motions,” Stiles said. “Rest is as important as the weight room or shooting 100 free throws a day or running 50 miles per week.”

Body image and maintaining a healthy diet while training can also prove challenging for athletes, affecting both their physical and mental health. Within the athletes’ world, DeYoung believes social media is a large contributor to athletes’ body image issues.

“It’s so hard to not pay attention to social media and any kind of media [when] they’re always showing you the ‘perfect body,’ which is really skinny,” DeYoung said.

Nock believes this unhealthy mindset has become increasingly prevalent in the running community.

“‘If you are thinner, you’re going to be faster.’ And that’s like drilled into your mind,” Nock said. “[The running community] thinks if you don’t eat, you’re gonna do better.”

After personally experiencing this struggle before participating in high school sports, Woods has found that improper nutrition had made her more susceptible to injury.

“When I didn’t get enough food [and] when I was pretty malnourished, that’s when I really started getting injuries,” Woods said. “I never had shin problems until I wasn’t eating enough.”

However, Woods believes that her coaches at West have had a positive impact on athletes’ nutrition by promoting healthy eating habits and the importance of a balanced diet.

“[My coach] did a really good job promoting just getting a lot of fuel and food … making sure he doesn’t ever pressure us to eat too little,” said Woods. “[They] also had a dietitian come talk to us about food … so I’m just glad that they’re smart about it.”

More than a medal

Through wins and losses, practices and competitions, coaches are there with the team through it all. Loussaert believes that maintaining an understanding and positive relationship between players and coaches is vital in establishing a successful team environment.

“The coach has the ability to determine the success of the team,” Loussaert said. “I think it’s really important for coaches to establish open communication with injuries and mental health.”

Nock agrees that coaches have a major impact on helping athletes stay engaged in their sport and creating a positive team environment.

“If you can’t keep your athletes in love with the sport and working hard, you’re never going to win,” Nock said.

Finding ways to connect with his teammates off the field has helped Houston cultivate a positive team culture.

“We do a really good job of just talking with each other and catching up on our lives,” Houston said. “It’s all about that system you have in place with your team and making sure you’re like a close-knit family.”

To facilitate a healthy team environment, Hartwig recognizes that football only accounts for one aspect of athletes’ lives.

“We forget we are dealing with young athletes who have a life outside of our sport,” Hartwig said. “I often have to remind myself that football is only part of a students’ day, and it is not the most important part to many.”

While winning is satisfying, Villarini believes sports have the ability to teach important lessons, and coaches play a vital role in doing so.

“It’s more than winning. Sports can teach us a lot about life, [its] struggles and how to cope and deal with pressure,” Villarini said. “I think the ultimate goal of coaches is to teach life lessons and to teach [athletes] how to cope with pressure, success and failures.”

One of these lessons that Nock has learned as an athlete is to maintain a healthy balance between all parts of her life.

“We are people before we are students, and we’re students before athletes,” Nock said. “We’re all trying to balance everything going on in our lives, and if we can’t give 100% every single day, it’s not a cause to bring us down.”