Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

We are the BSU

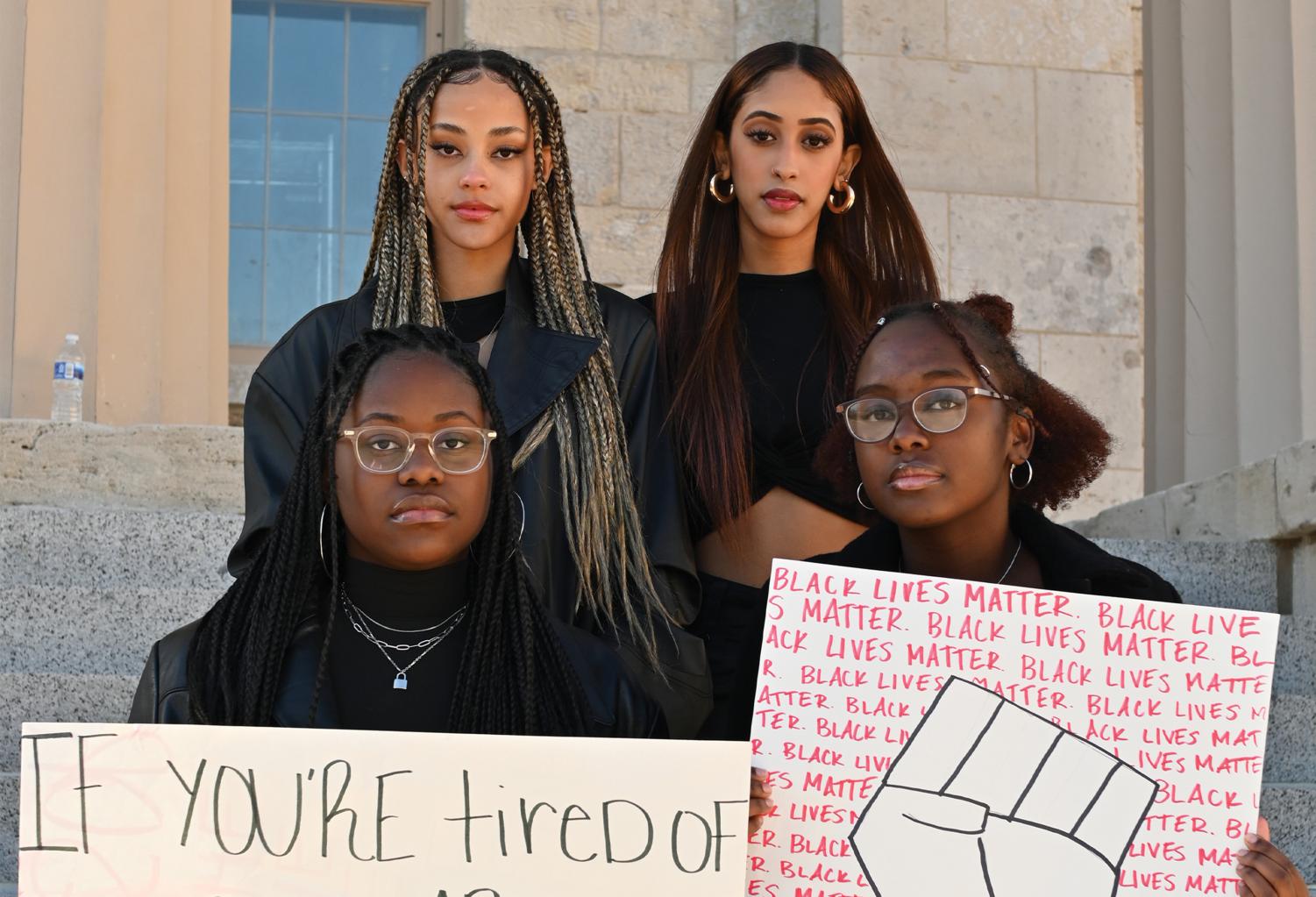

Following the Nov. 8 BLM protest, students took the lead in reestablishing West High’s Black Student Union.

January 21, 2022

Ripping out pages from her notebook in the Little Theatre, Nisreen Elgaali ’22 decided it was time to turn students’ words and emotions into action. Following a meeting with West administration that many students felt was going nowhere, Bernadetta Kariuki ’22 recalls sitting beside Elgaali in confusion.

“I asked her what she was doing, and she told me that she wanted to protest around the school and just have people write on [the papers],” Kariuki said. “So we went back to the Little Theatre and we started writing.”

Shortly after, Annie Gudenkauf, West High’s Student Family Advocate, brought them more materials to use. Once the posters were complete, Elgaali stood outside the Little Theatre to pass them out. Soon, students raised their handmade signs, sparking the protest that would soon ignite the recreation of West’s Black Student Union.

Forming the BSU

The BSU leaders, including Co-President Maria Kazembe ’22, stress its necessity at West High.

“I felt that a lot of us felt like we had no control or no power, and so by establishing the BSU, we were like, ‘Okay, well, obviously, we can’t rely on the people to give us power, so we’re going to empower ourselves,’” Kazembe said.

After a video of a student making threatening, racist remarks surfaced on social media, West High administration held a meeting in the Little Theatre the following Monday, Nov. 8, to provide a “safe space to discuss and process the harm this has caused,” according to a schoolwide email sent out the Sunday before. However, for students like Rawan Babiker ’25, the meeting was not enough.

“It got to a point where people had to physically show their anger and how frustrated they were and take matters into their own hands,” Babiker said.

After Co-President Elgaali initiated the poster-making and protesting, the group grew. With posters ready, they began marching around the school, shouting “Black Lives Matter” and calling for justice. The group of students continued to grow as they marched through the school, went to the front lawn and made their way to the cafeteria during A Lunch. They used lunch tables as their stage and made their voices heard. BSU’s Athletic Affairs Advisor Talyia Ochola ’22 describes how she felt throughout the march.

“It was empowering, walking around and knowing that people had to be hearing us. Even if they were ignoring us, they had to [hear us] because we were all right there,” Ochola said. “[People] could no longer say, ‘We didn’t know what’s happening. We don’t know what’s going on. You guys aren’t actually being targeted or anything,’ when we all get together and show how many people are actually affected and hurt by these things.”

After gathering in the cafeteria, the protesters met in the Little Theatre again for B Lunch. The congregation of Black students in the school for the protest created a sense of unity that Kariuki, Social Media Coordinator of the BSU, had not experienced before.

“That was like the first time I actually felt unified in this school because I’ve never really felt connected … to other students,” Kariuki said. “I was just really proud of us.”

After the protests, members of the ICCSD Equity Board met with the students in the Little Theatre to listen to their experiences. Hearing these testimonies made the soon-to-be BSU leaders realize there was more to be done. Kazembe brought up the idea of reforming the BSU, and she and Elgaali, along with Kariuki and Ochola, united to take action.

“I guess we were all just filled with emotion. We actually realized things need to change at that moment and the only way that it’s going to change is if we continue to do things like protest and use our voice, and we can’t just leave it up to the administration and going to our teachers,” Kariuki said. “We have to do something ourselves as a student-led organization.”

Throughout the day, some students viewed the protest in a negative light. Fights broke out that afternoon, leading to rumors linking them to the protest. However, these conflicts were unrelated to the protest.

“None of us were violent, and I think that sometimes, yes, it was a little bit disruptive, but has our learning not also been disrupted?” Kazembe said. “Through threats in the hallways, online — it doesn’t matter where Black students go, we are always just being threatened.”

Shortly after the first November protest, the four leaders took their work and ideas and met with the West High administration. They laid out expectations regarding meetings and communication with administrators and connected with other community members, such as the Northwest Junior High BSU adviser, Taylor Scudder.

What is the BSU?

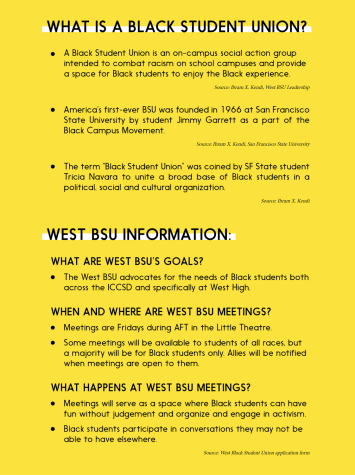

The first BSU was founded in 1966 at San Francisco State University as a part of the Black Campus Movement aiming to reform higher education. Eventually, their mission shifted towards a common goal for all Black Student Unions: to unify and empower Black students in the struggle for equality. Elgaali believes that even though progress towards equality has been made, a BSU continues to be crucial today in fighting back as people become confident in their ignorance.

“Just because Jim Crow is not a thing anymore, just because the things that used to be in our faces aren’t in our faces anymore and it’s just hidden systemically, doesn’t mean that things got all the way better,” Elgaali said.

West High had a BSU last year, which held meetings online due to COVID-19. Former social studies teacher Amira Nash was the adviser. However, once Nash left for a job at the University of Iowa, the BSU disbanded. Now, the newly reestablished BSU operates differently than last year’s — meetings are in person and student-led.

“I think it was a student effort,” said Assistant Principal Maureen Head. “They just told us, ‘This is something that we need to feel supported, and this is something that we need as Black students at West.’”

Part of the BSU’s purpose is to create a support system for Black students in the form of meetings where they can be around each other and feel like themselves. This is why some meetings are for Black students only while some welcome allies.

The first BSU meeting occurred during AFT in the Little Theatre Nov. 19. After the meeting, some BSU members participated in a district-wide walkout to the Pentacrest, marching and chanting with posters to raise awareness about racism in the district. Prior to the walkout, West administration sent an email to staff and parents expressing their support of students’ right to protest and use their voices.

The BSU’s next meeting was dedicated to mental health. The meeting was for Black students only where they watched Netflix, had snacks, made bracelets and played card games. There was also a restorative justice circle for anyone who wanted to talk about the events happening at school and to have a support system in processing them. Kazembe feels this meeting created a necessary place for students to just be kids.

“It’s sad they have to look for places to just be themselves, but I’m happy that I can see people who I have never seen smile before, smile … I can see people that I’ve never seen genuinely laugh, laugh,” Kazembe said. “I’m just so happy that they have a place to be their true, authentic selves.”

The BSU is meant to be a safe space for Black students of all different identities and embraces that being Black does not have a definite “look.”

“The BSU is for everybody who supports Black students, [and] not only just Black students, but queer Black students, Muslim Black students, Asian Black students,” Elgaali said. “There’s so many intersectionalities that go into [being Black].”

Along with providing a sense of community, the BSU is advocating for Black students within the district. Through the formative process, the BSU continues to meet with administration as well as attend school board meetings. Often, board members or workers in the district will ask the leaders for clear examples of things students have experienced to gauge the problems and better formulate solutions. To do this, the leaders share students’ testimonies with permission.

Kariuki wants people to know the BSU strives to make a difference and acknowledges part of that may have to be through making some noise.

“We’re here to peacefully make a difference,” Kariuki said. “We’ve never ever tried to do anything violent, and we’ve never purposely tried to upset anybody, but we also know that upsetting people is the way that we’re gonna get change.”

Part of the BSU’s advocacy for change is done through protests such as the walkout. It saddens Kariuki to hear about peers who feel the protests are only a disturbance.

“I feel like the reason why they also feel [protests are disruptive] is just because the school has done such a poor job of being transparent with the problems within West,” Kariuki said. “I wouldn’t necessarily just blame them, but also encourage them to try and understand why we’ve done stuff like that.”

Elgaali agrees that administration has not been transparent. However, she believes there has been improvement since the BSU began meeting with administrators.

Through protests and meetings, the BSU leaders hope to raise awareness for racial injustices students are not aware of.

“A big thing is awareness, because I know I’ve heard so many [white] people say ‘That doesn’t actually happen,’ so it’s like, ‘Yeah, it doesn’t happen to you,’” Ochola said. “Some people are still just going to want to live in ignorance to ignore the fact that they are the problem.”

Pathway hurdles

Before starting the BSU or even initiating the protest, the BSU leaders faced their own share of racism throughout their high school years.

“It’s not exactly what people say directly to you, but it’s just the way that people look at you or people treat you [though] they might not understand that they’re doing it intentionally,” Kariuki said. “I feel like for the first few days that you’re in an AP class, you just have to really measure up to your classmates and measure up to your teacher’s expectations.”

Elgaali believes the social culture of microaggressions, along with systemic issues, have led to different high school experiences based on race. She sees the negative mental and educational impacts these can have on students of color.

“It makes it a lot harder for students to learn when their own teachers don’t believe in them and say things like, ‘Oh, you’re gonna end up working at McDonald’s when you grow up,’” Elgaali said. “It also just causes pressure on Black students to conform to the stereotypes that are in our school.”

Head, class of 2000 West graduate and person of color, understands the need for students of color to sometimes disrupt the learning environment.

“It’s hard being a student of color in an institution that historically has marginalized them before,” Head said.

As Black students at West High, there are many challenges that come at the expense of their education. Principal Mitch Gross assures that the administration does its best to address racially-motivated actions, although they cannot give details on these occurrences. This is because every administrator is bound by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, or FERPA.

“[FERPA] prohibits us from talking about specific disciplines. It prohibits us from talking about specific students who have done things,” Gross said.

However, the lack of transparency the law requires can be frustrating for many students.

“[Those affected] won’t be able to reach peace; they won’t be able to come to their senses about what happens and they won’t feel as if they’re being comforted at all,” Ochola said.

These feelings of dismissal from administrators can be attributed partially to the difficulties the BSU faced in securing a Friday AFT meeting time. With the required district-wide social-emotional learning lessons taking place during that time, it was difficult to schedule Friday meetings. According to Elgaali, the administration also initially restricted them to one meeting per month, but after some discussion, a weekly meeting time and place were established.

Along with establishment challenges, the BSU leaders have also faced backlash. Ochola has received anonymous death threats via social media and feels unsafe because of them.

“I think safety is a really big [concern] because we’re not only worried for ourselves, but also … we’re worried for our members,” Ochola said. “We want them to have that space — to talk and share their testimonies and everything like that — but ensuring that they know the possible backlash that could happen with that is tough.”

Elgaali also received social media threats, which went as far as telling her they would kill or hang the BSU leaders. The school alerted the Iowa City Police Department, or the ICPD, and an incident report was filed Nov. 12. According to Elgaali, she left voicemails for an officer to follow up on the investigation, but those messages went unreturned. The WSS reached out to the ICPD and the officer. As of press time, the officer did not respond, but an ICPD representative wrote in an email, “The ICPD is not always able to speak on the details of an investigation and we cannot disclose the identities of juveniles involved in an investigation whether they are the victim, witness, or suspect … The ICPD always has the safety of students and the community as a top priority and investigates all reports made to us with the spirit of serving and protecting victims of crime.”

With the publicity of the protest and BSU formation, the BSU leaders found themselves and their efforts placed under a spotlight, with many news organizations reaching out about interviews and teachers pressuring Black students about whether they will protest during class. Although Kariuki feels a significant amount of pressure from the attention the BSU receives, she believes it is worth it to continue to work towards their goals.

“Some of it just becomes a little bit nerve-wracking, but we understand that we’re doing something that’s very important, and it’s okay to be nervous,” Kariuki said.

These factors, as well as the struggles that Black students face on a day-to-day basis, can take a toll on their mental health.

“I think, quite frankly, it’s been exhausting for a lot of the kids involved, plus just the exhaustion of going through the school experience as a student of color,” Head said. “I think the most important thing to keep in mind is we all want the same thing.”

With these challenges, having supportive teachers and allies in the school is increasingly important to BSU members.

Standing with the BSU

Following the Nov. 8 BLM protest, students took the lead in reestablishing West High’s Black Student Union.

After the video surfaced and the protest occurred, it was difficult for some to return to the mindset needed for classes due to their mental well-being and discomfort around certain teachers and students. Kariuki feels teachers were more focused on the fact that students had missed their classes than supporting students’ efforts and checking in on their mental health.

“Sometimes you have to put school as a second priority, and coming back to school where teachers are not supportive and they’re just kind of taking it personally really does make it harder for us to do things that we need to do,” Kariuki said. “Teachers offering that space and letting you know that they’re on your side and just also respecting boundaries — that would really help.”

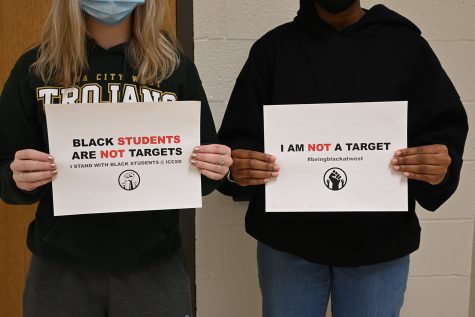

Some of the best ways the leaders believe teachers can support their Black students and show that their classroom is a safe space is to show solidarity by putting up the “Black students are not targets” signs or the sign on the inside cover of this issue on their classroom door. The BSU leaders believe teachers should reach out to Black students and be understanding when students miss classes for protests. Kariuki also hopes they will not fall into the mindset that protests of this nature are excessive or of disturbance.

“When I hear that [teachers are] just saying it’s a disruption, they’re really just skimming the surface of everything, and they’re not even digging deeper to what we’re saying,” Kariuki said. “It kind of just seems like they’re purposely ignoring us.”

The leaders also encourage teachers to share information directly or open a space for BSU members to talk about upcoming protests and meetings. Sharing information and spreading the message of the BSU is something that not only teachers can do but so can students. The leaders encourage raising awareness and promoting the BSU by following their social media account on Instagram, @icwestbsu, and sharing their posts. Anyone can be involved in the movement regardless of race, and allies are appreciated. Babiker emphasizes the importance of not letting racism slip by, especially in the presence of peers.

“Check your friends as a white ally,” Babiker said. “You have to check your friends and tell them it’s not okay to say racist stuff [including] stereotypes [and] colorism … don’t let them get away with it.”

Along with actively standing up against racism, Kazembe feels that just checking in on Black friends, especially in the light of recent racist events, can go a long way.

“I think it’d be really good for everybody to check in on their Black friends because our mental health has not been considered in the past,” Kazembe said. “It shows a lot of your character if you’re gonna reach out to individuals who have been hurting.”

One of the biggest goals of the BSU is changing the social culture surrounding race in school, the tolerance of racism by individuals, and the internal biases that some staff members have. A big part of this, Kariuki describes, is better equipping teachers with more knowledge regarding race.

“Part of it too is implementing teacher training and racial sensitivity and just learning about that, which they already have, but it isn’t enforced well enough, which is why there are still problems,” Kariuki said.

Head recognizes that a big part of creating change will be in training and creating culturally responsive educators, which has been something the administration had been working on before the protests. However, an obstacle to this is Iowa Law HF-802, which prevents staff from receiving certain implicit bias training they have had in the past.

Another of Ochola’s goals for the BSU is to implement more definitive and specific disciplinary actions for racism. Just like if a student uses their phone three times in class, it gets taken away, there should be a standard set of consequences for each incident of racism. She hopes this will help secure a more safe school environment.

According to Gross, the school follows certain disciplinary actions based on a handbook entitled “Disciplinary Protocols and Procedures,” which contains instructions and consequences based on the issue.

“We’re a serious organization and we want to take action. I want to see action taken, and we want to make sure that all schools, not only West High, are actually a safe place for Black students, and it actually does promote equality and doesn’t stand for racism,” Ochola said.

One of the ways the BSU is working to ensure that West High is a safe and receptive environment for Black students is by working with other schools in the area. The BSU leaders hope to inspire other Black students beyond West High and across the district to start or continue their own BSU. They have gone to Northwest Junior High to connect with the Black students and their BSU as well as Liberty High and City High to help them start or restart their own BSU. They are also working to connect their BSU members to older role models which they can draw their own inspiration from, like students attending Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

“We kind of just thought of it as a large scope of just doing stuff for racial injustice for Black people everywhere and for future generations that are gonna come to West,” Kariuki said. “It further inspires us to keep doing what we’re doing.”

Elgaali is passionate about the work the BSU is doing and emphasizes how important the community has been for her.

“The BSU means the world to me,” Elgaali said. “I feel like with the BSU I have been able to help and reach out to the most students I’ve ever been able to throughout my high school career.”

Looking towards the future, Kazembe is determined that the BSU will always be present to provide Black students a platform to speak and not be judged for who they are and the experiences that they’ve had.

“I want them to know that we are 100% here for them. This is not a show. This is gonna be here tomorrow. It’s gonna be here the next day. It’s gonna be here in a month, next year, we’re still going to be here,” Kazembe said. “We are here to make change, and we’re not going to stop until we get that change.”