Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Beauty Beyond Bodies

West students share their experiences with eating disorders, self-harm scars and body dysmorphia.

May 18, 2023

As summer approaches, many students replace their sweaters and sweatpants with t-shirts and shorts. For some, more revealing clothes are just another way to combat the heat, but for others, it can invoke self-consciousness. A study from C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital shows that up to 73% of teenage girls and 69% of teenage boys express negative perceptions of their bodies. Eating disorders, body dysmorphia and scars can be reasons why these insecurities become more prevalent.

Eating Disorders

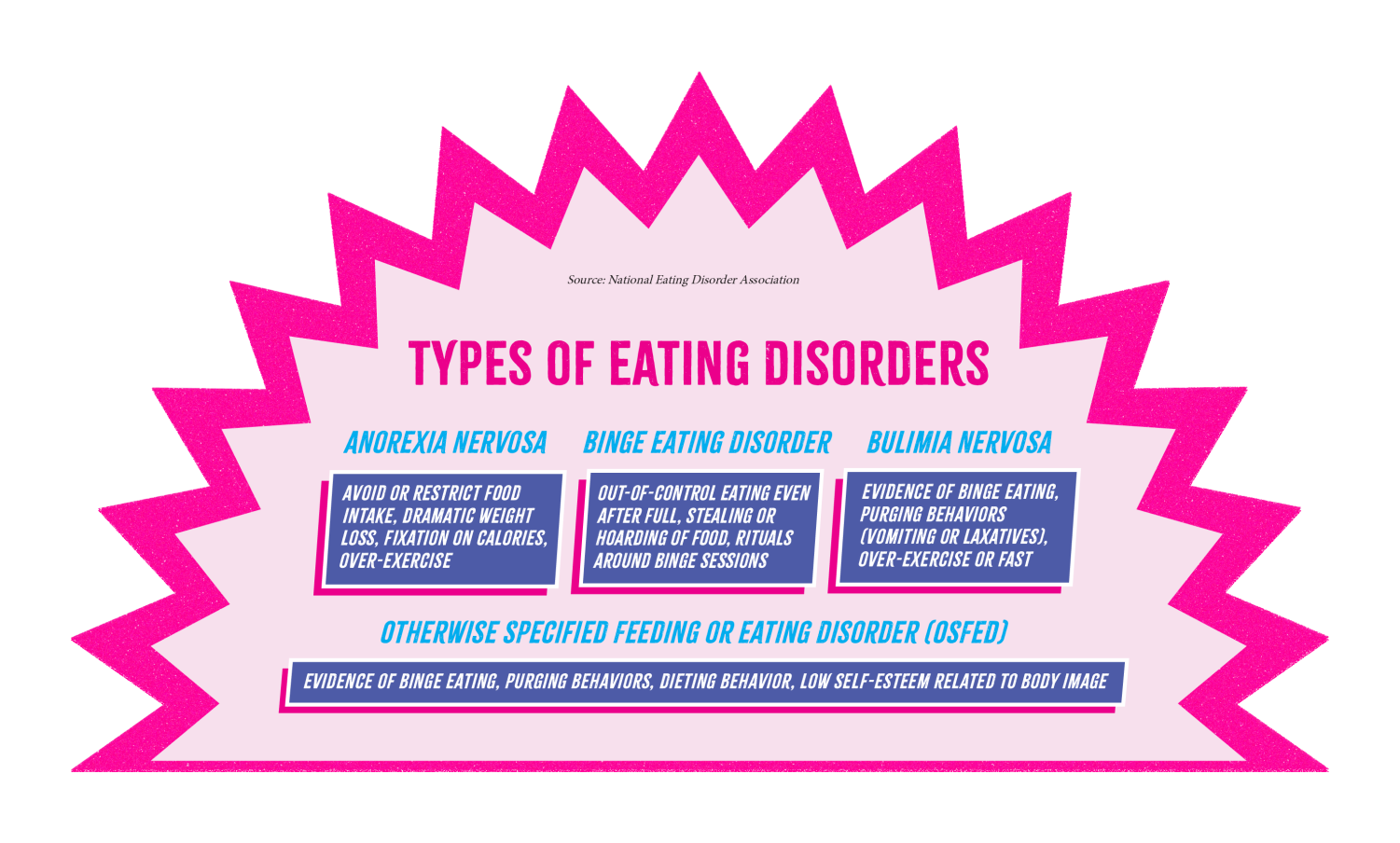

The American Psychiatric Association defines eating disorders as behavioral conditions characterized by extreme and continuous negative eating habits and related distressing thoughts and emotions. Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. Many develop these in adolescence and young adulthood, affecting 5% of the total United States population.

Grey Gromacki ’26 was diagnosed with anorexia, which often meant counting calories and not eating food for long periods of time. They first experienced symptoms in eighth grade due to the social environment.

“It didn’t just happen one day, it started socially,” Gromacki said. “My anorexia was influenced by other people’s disordered eating habits. I would see people not eat lunch for days on end, and I was like, ‘Oh, that’s normal,’ even though it wasn’t. But because I put my trust in people that I cared for, I saw that as a sense of normalcy.”

Ijin Shim ’24 was also influenced by her peers. While Shim was never diagnosed, she developed disordered eating habits at the start of her freshman year cross country season.

“There is the stereotypical runner’s body: very thin [and] lean. During the summer, we wear tank tops and sports bras to run because it is hot. You start to compare yourself to other people’s bodies, and when you realize that you don’t have that stereotypical body, you think you’re fat,” Shim said.

For some, once negative thoughts begin, they can spiral into destructive habits. Gromacki became more reliant on their anorexia as a coping mechanism for a sense of security and control, especially during their parents’ divorce.

“Eating disorders are mental. The reason that you feel like you can’t eat is because of an outside problem that you’re ignoring by taking control of your food intake. You feel like an eating disorder becomes your friend; it feels like someone that you can talk to,” Gromacki said. “Having control around something, even if it was slowly killing me, was something that I felt comfortable with. That’s why so many people don’t want to recover, because there’s a voice in their heads being like, ‘I’m in control. I feel better this way.’”

Eating disorders affect every part of life, not just eating. Other manifestations of eating disorders include withdrawal from activities or friends and body dysmorphia. Besides significant weight loss or gain, common physical symptoms of an eating disorder include stomach cramps, fatigue, dry skin and trouble with sleep.

Due to the lack of nutrition in their body, Gromacki struggled with swollen feet and always felt cold. They also had trouble focusing in school due to constant feelings of exhaustion.

“When I was at the height of my eating disorder, I was very lightheaded. You feel like you can’t focus. Sitting in class, you’re just thinking about food all the time. But you’re also thinking, ‘Oh my god, how long have I gone without eating? How many calories were these?’” Gromacki said. “When I started getting better, I was like, ‘What the heck, life is fun? I can be happy?’”

Similar to many athletes that experience disordered eating, the harder Shim strived to achieve a stereotypical runner’s body, the further she was from becoming a better runner. Her eating habits caused a decline in her performance and health.

“One day [at cross country], I passed out. I don’t even remember what happened but [suddenly] I was in an ambulance to the ER because I wasn’t eating enough. I thought I was going to die. I couldn’t move my body at all,” Shim said.

Shim believes another reason teenagers develop eating disorders is the lack of elaborate nutrition education they receive.

“[Coaches need] to make sure all their athletes are healthy and have the right food and fuel for their bodies, but those are the things that we forget and are not educated about,” Shim said.

For Gromacki, the path to recovery started with a diagnosis from their therapist. They felt relieved to give their struggle a name and a reason; acknowledging the problem motivated Gromacki to heal.

“The biggest thing that helped me recover was realizing that I can take control of my own life if I choose to want to get better,” Gromacki said. “It’s very difficult because you’re constantly fighting against yourself, but that doesn’t mean it’s impossible.”

As for those who want to lose weight, Shim believes that it should be done through a healthy, balanced diet and exercise routine.

“There’s nothing wrong with wanting to get skinny or wanting to have a specific body type. It’s the way you [achieve] it; a lot of times, it’s not the right way,” Shim said. “[Disordered eating] is very unhealthy and dangerous for your body, and I think that’s what we don’t realize.”

Shim stresses the importance of surrounding yourself with people who influence you positively to live a healthy life.

“Friends influence you, your life and your eating habits. Those are the people you spend the most time with and who give you the most feedback and comments about yourself,” Shim said. “Everyone has a different body and different lifestyle. You can get tips but that doesn’t mean you can copy and paste everything they do into your lifestyle.”

Gromacki agrees and has learned to be patient with themself, emphasizing that recovery is never linear and relapse can be a part of the process.

“If you really feel like you’re struggling to find motivation [to change], then talk to somebody. If you truly want to get better [or] need to get better, having a support system is good,” Gromacki said.

Body Dysmorphia

Body Dysmorphic Disorder is a mental health condition in which thoughts about perceived defects or flaws in appearance constantly intrude one’s mind, according to the Mayo Clinic. Anxiety Institute states that BDD often develops during adolescence, affecting 2% of both males and females in the United States. Body dysmorphia can impact teenagers differently; some females often express discontent with body fat, facial hair and complexion, while some males express dissatisfaction regarding a muscular physique, acne and height.

Body dysmorphia in men is underrepresented as they are less likely to reach out for help, according to The Newport Institute. For weightlifter, track and field runner and football player Seth Overton ’23, body dysmorphia, specifically muscle dysmorphia, impacts his confidence and everyday life.

“[Masculinity] is where I get my body dysmorphia [from]. I feel like I’m too small and not masculine enough. I’ve always been kind of super skinny [and] didn’t have any muscle,” Overton said. “No matter how hard I work [or] how I physically look, I will think of myself as less than and not up to par. No matter how much affirmation people give me, I still never see it.”

On the contrary, Gromacki’s body dysmorphia originated from their eating disorder, often leading to feelings of self-hatred or resentment.

“I hated myself. I didn’t want to look at myself. I was mad at myself every time I looked in the mirror,” Gromacki said. “I was like, ‘Why do I look like this?’”

Shim believes the impacts of body dysmorphia have become normalized among students.

“I’ll be hanging out with my friend and they would be like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m so fat,’” Shim said. “I think a lot of times they need validation from other people [to say] they aren’t [because] your head keeps telling you, ‘You’re fat, you’re fat.’”

Gromacki and Overton acknowledge how those struggling will often hide their appearance by staying at home, keeping to themselves, wearing makeup or switching up their wardrobe.

“One of the main [coping mechanisms] is not wearing stuff that you can see your body in. A lot of people wear baggy clothes to hide their body or they’ll wear super tight-fitting [clothes] to try [and] show off everything they have,” Overton said.

Overton also believes many lifters struggle with body dysmorphia due to pressure from social media to achieve an idolized body type, leading to compulsive actions or obsessive thoughts.

“You’ll see these bodybuilders that are on performance-enhancing drugs; they’re super big, super lean and they look great. But then you compare that to your own body, when you’re not taking performance-enhancing drugs and think you look small,” Overton said.

In addition to medication and cognitive behavioral therapy, Gromacki mentions that caring for yourself can effectively combat body dysmorphia.

“I faked confidence for a long time because I wasn’t confident in myself, but I wanted to be perceived that way. As I faked it more, I just started not caring, and I just had confidence,” Gromacki said. “I think the biggest way that I combated [body dysmorphia] was by starting to try to love myself in general rather than just my body. [I found] things about myself that I like, things that made me feel good about myself. As I got better, it was easier to love myself because there was less self-hate.”

Self-Harm Scars

Self-harm is injury inflicted on oneself on purpose, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness. It is an unsafe approach to cope with emotional pain, despair, anger and stress. The National Library of Medicine states that 14% to 21% of high schoolers self-harm. Self-harm is significantly more prevalent among teenage girls, with ninth grade girls committing self-harm at three times the rate of ninth grade boys. Those who have experienced trauma, neglect or abuse are among the most vulnerable.

Forms of self-harm include cutting, burning or hitting oneself. These can lead to fresh wounds in patterns, which can cause feelings of shame, as scarring can be permanent. To hide these scars, people often wear long-sleeved shirts or pants.

Serene Hamzeh ’24 has had self-harm scars on her legs, arms, waistline and ribs for the last two years.

“They are kind of hard to look at sometimes, just knowing that if they’ve healed, then they’re there forever,” Hamzeh said. “But it also does show me how much I’ve gone through and how much I’ve overcome as well. It helps me [think], ‘I’ve gone through this; I can get through anything.’”

Hamzeh finds that when self-harm scars are regarded as ‘just for attention,’ critical mental health issues are dismissed, creating a harmful stigma that can prevent individuals from getting help.

“People say, ‘If you’re showing your scars, you’re doing it for attention.’ And even if you’re not showing them, people will still say it’s for attention,” Hamzeh said. “Sometimes, it could be a cry for help.”

Hamzeh advises covering up fresh self-harm scars to reduce the likelihood of infection and not trigger others who are struggling. However, self-harm scars should be treated like any other skin once healed. Despite this, Hamzeh has struggled with wearing short sleeves in public.

“It’s definitely hard being able to look in the mirror like, ‘Okay, that’s what everybody’s gonna see,’ and knowing that I’m going to walk past strangers outside and they’re probably going to notice. I get looks all the time,” Hamzeh said. “But knowing that a lot of people struggle with the same thing as I do will probably help people become more confident with their [scars] … People should get to wear whatever they want.”

Hamzeh believes it is rude to point out self-harm scars in public or ask personal questions, as it can make people self-conscious about an already sensitive topic. A better alternative is to check-in on the person privately.

“It’s difficult to know how to react to certain things. You can’t get upset at certain people who are genuinely just curious or worried,” Hamzeh said. “I used to say it’s personal, or I laugh it off. It’s still an awkward thing for me to talk about.”

While wearing short sleeves, Hamzeh always brings a light sweatshirt or jacket to conceal her scars if she gets uncomfortable. She acknowledges it takes time to get used to the change and the importance of a supportive environment.

“Surround yourself with people who don’t mind [scars]. I don’t think anyone should ever mind it because it’s just something [they have] gone through, but it doesn’t make up who they are. It’s a part of their journey, not their whole personality,” Hamzeh said. “It should not be a big deal to people around you if they know that you’re safe, you’re doing okay and you’re getting the help you need.”