Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Concussed.

As concussions have become more common throughout the past decade, West Side Story investigates the effect they can have on student-athletes and how their treatment is advancing.

November 14, 2017

Effects and protocol

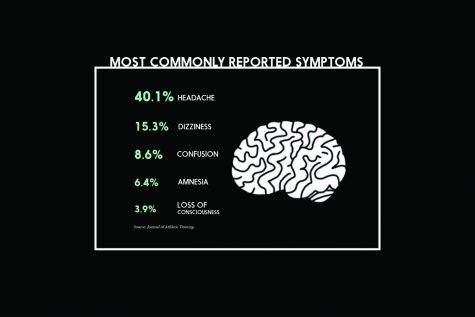

Most students and athletes know the common symptoms of a concussion: headache, dizziness, confusion, but what many don’t know are the feelings of debilitation and darkness experienced.

Ella Gibson ’18 stated that she “fell to the ground and just sat there for a second when everything was just dark” after getting her concussion, and Makhi Halvorsen ’20 described a similar experience. However, Gibson continued to cheer while Halvorsen sat out for the rest of his football practice.

Grace Miler ’19 illustrated lesser-grade symptoms when she first received her concussion, but reflecting on the injury made her change her opinions of it.

“I did not [pass out], I stayed standing up and I was able to kind of comprehend what was happening, but I could not see very well,” she said. “It made me realize how easy it is to get a concussion and how much it can affect you. When I used to hear that people got a concussion I thought that they just had a headache, but no. It hurts really bad, and it is something pretty serious.”

After an athlete has suffered a concussion, there is a strict protocol that must be followed to ensure that there are no further damages. The protocol begins 24 hours after the symptoms have completely dissipated. The two protocols that are most prevalent at West are the REAP and SCAT5 test.

“The REAP protocol is the concussion management for the education side of recovery. The protocol stands for remove/reduce, educate, adjust/accommodate or pace. So, it is reducing the amount school work that piles up after a concussion when a kid misses school, allowing them rest time while they are returning from a concussion,” athletic trainer Sheila Stiles said.

The SCAT5 is the most common test used to diagnose a concussion on the sidelines. But, the SCAT5 is a lot more effective if there is a neurocognitive baseline to compare to. This can be done by the athletic trainer and does not require a doctor to diagnose or treat an athlete, according to pediatric sports medicine specialist Andrew Peterson.

“I don’t mind being the one to manage the concussion but also if someone is really having some lingering symptoms or really struggling and I can’t get a handle on it that’s when I really try to push for [University of Iowa Sports Medicine] for the Concussion Clinic,” Stiles said.

Not only was the effect of a concussion immediate on these athletes’ ability to practice and compete, it also affected them in the classroom. At first, Halvorsen did not take a concussion test or know the culprit of his symptoms. This led to a drop in his ability to perform well in class.

“It was kind of hard remembering stuff for school, but it’s slowly starting to come back,” he said roughly two weeks after first diagnosed. “My grades most definitely dropped for a little bit because [I] didn’t really know what was happening.”

Now, teachers are emailed to fill them in on the brain injury their student is experiencing. Just as athletes undergo a ‘return to play’ protocol, the cognitive delays may promote a similar ‘return to learning’ time period, which is usually within three weeks according the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“‘Return to learn’ is the concept behind [students returning to school],” Dr. Granner said. “It’s not something that coaches and trainers only have to know about, it’s something that teachers have to broadly be aware of, too.”

The time frame effects stay prevalent in the brain vary widely based on the person. Dr. Peterson states that the “average duration of symptoms is eight days. Our best data is in high school boys where 95% of people are healed by the 1 month mark and 99.5% of people are healed by the 6 month mark.”

At West High, athletes can expect to be sitting out for at least five days following diagnosis. This is because it will take this long to go through protocol to be ready to compete, but for many it takes longer than this. Stiles says that on average, athletes will not practice for “a week to two weeks. But there’s definitely those cases that are a lot longer and there’s those cases that are right at the five days.”

ImPACT testing

Before the start of seven team’s season they participate in ImPACT testing. This test is performed to consult to if an athlete suffers a concussion during their season.

“Our contact sport athletes: [girls and boys] basketball, football, wrestling and [girls and boys] soccer do ImPACT testing. It’s based solely on their performance alone it’s not compared to anybody else. If their scores are similar or better to the scores they took at the baseline then we know their brain is most likely ready to return to to activity,” Stiles said.

This year, the volleyball team has also been added to the list of teams that take the test. This baseline has become almost vital to diagnosing and recovering from concussions since there has never been a quantifiable method available before.

“Concussions are diagnosed by signs and symptoms. It’s not something that you can take an MRI scan of. It goes by what do we see as the medical professionals and what people report to us on how they’re feeling after a traumatic brain incident. So, the test gives us tangible data to go off of how the kid is progressing or not progressing and how they feel immediately after having an episode,” Stiles said.

However, Gibson believes that she received lesser quality treatment due to the fact that cheerleading does not participate in ImPACT testing.

“I mean it felt a little different just because there wasn’t much structure to how I went through things. I’d heard from all my friends [on the football team] they do testing before the season even starts to compare it to if they get [a concussion] during the season. So, there’s nothing to compare my scores to. It’s all based on how I feel and so I was just basically going off nothing,” Gibson said.

Since the number of concussions has increased, Stiles believes that ImPACT testing should be extended to the cheerleading team as well.

“The research is showing a high incidence of concussions in the sport of cheerleading and especially when we have the competitive cheer to where they’re doing more tumbling,” Stiles said.

Although ImPACT Testing is a positive step to finally solving the mystery of concussions, there are also some drawbacks to using this test.

“The ImPACT [Test] is a double edged sword. You can do really well on your baseline and then never get back to that,” Stiles said

Damages to brain function

A few areas of the brain can be pinpointed as promoting the most symptoms. Specifically, global cerebral dysfunction can cause several other parts of this organ to be injured, according to Peterson.

“Your brain sits inside your skull in some fluid. When you hit your head, your brain can slam against the skull where it hit or it could also go backwards like [a] whiplash effect. Or there can also be some sort of shearing, like spinning,” said Stiles.

As the control center for the body, it can cause numerous other organs to malfunction, especially those located near the head and neck.

“Your occipital lobe is in the very back and that controls your eyes. So that’s where you might see double vision problems in general and the light bothering you,” Stiles said.

This makes it more common for athletes to experience blackouts and issues pertaining to vision upon injury, such as those that Halvorsen did.

“I just felt really slow and I blacked out, which kind of scared me because I kind of lost my breath and came back. Everything was darker,” he said.

Knowing the effects

Despite knowing the dangers of concussions, neurologist Mark Granner allowed his son, Alex Granner ’18, to play football in sixth grade.

“We considered it pretty carefully. We understood there was risk of traumatic brain injury, including concussion risk. In fact, one of the kids he played basketball with at that time had already had a concussion earlier in fifth grade when he was playing tackle football,” Dr. Granner said.

“I think behind the scenes, his mom and I, were hoping he didn’t really go farther than that and that’s what ended up happening,” he said.

In line with his parents’ beliefs, Alex decided after one year that he did not enjoy the sport, causing him to choose to stop playing.

“They sort of steered me away from it because it’s not the best sport to play long-term. I didn’t like it either because … I only touched the ball like once per game,” Alex said.

Although Dr. Granner did not want his son to play the sport, he has held season tickets to Iowa football for twenty-five years.

“I cringe when I see players getting hit with the ball. I cringe when I see them going down on the turf,” he said. “It’s tough, knowing what the risks are to the brain and the nervous system. It’s a little bit conflicting.”

Future of sports

Since chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) was discovered in the early 2000s, knowledge on the subject has slowly begun to accumulate. However, it was not until its movie, Concussion, was released in late 2015 that the public began to worry about the condition.

Though it has been known for over a decade, there are still comparatively little known facts about CTE. Additionally, most of the research has been done on the brains of former professional football and hockey players, discluding many age groups and athletes.

“The brains that have been examined so far are people who’ve played professional football, but every professional football player played high school football and played college football, too, so it’s really not known if there’s a certain risk window or if stopping at a certain age reduces your risk or not,” Dr. Granner said.

The lack of evidence of a correlation between this condition and high school athletes may resolve in coming years, but for now students look to their diagnoses as signs of whether to continue participation in their sport.

“It also made me a lot more cautious about high school cheer and how unsafe it is, because in all my three years of cheering no one has ever gotten injured [as much],” Gibson said. “It’s been the first two months [and I have had] head-neck injuries, which shouldn’t be happening so that makes me a little nervous with it.”

Halvorsen, having never suffered a serious injury from football, was taken off guard when he was diagnosed with a concussion. Now back to playing, he takes safety into account when tackling.

“Now I’m just a little more cautious. I’m a little more safe with the way I hit people, because I didn’t like having a concussion, so I don’t want to give someone [one] even if it’s an accident,” he said.

Even before diagnosis, Halvorsen clashed with his mother on their opinions of football.

“She always tells me that later on in life people are just going to stop playing because they’re going to realize how bad of a sport it is because of injuries but it’s not going to stop me,” he said. “Personally I feel safe enough because it wasn’t a huge concussion. I feel like maybe if it was my second concussion or third then maybe I’d be more scared about it, might take a break for a year or something like that, [but] I feel like it’s very hard to get one. You don’t just get one from a little hit; it takes a big hit to get one.”

While having experienced this risk, Halvorsen still has a passion for the sport, driving him to keep playing after having experienced the head trauma.

“It’s my favorite thing to do,” he said. “I’m just going to keep going until I’m going to have to stop at some point but I’m just going to keep going.”

Dr. Granner, as a parent having experienced his son playing football, believes he members the demographic that may ultimately decide the fate of high-concussion sports.

“It’s impossible to make football a completely safe sport, but the reality is soccer isn’t a safe sport, or basketball isn’t completely a safe sport either,” he said. “If the sport faces an uncertain future, in my opinion it’s going to be in the hands of parents who either let their kids play or not.”