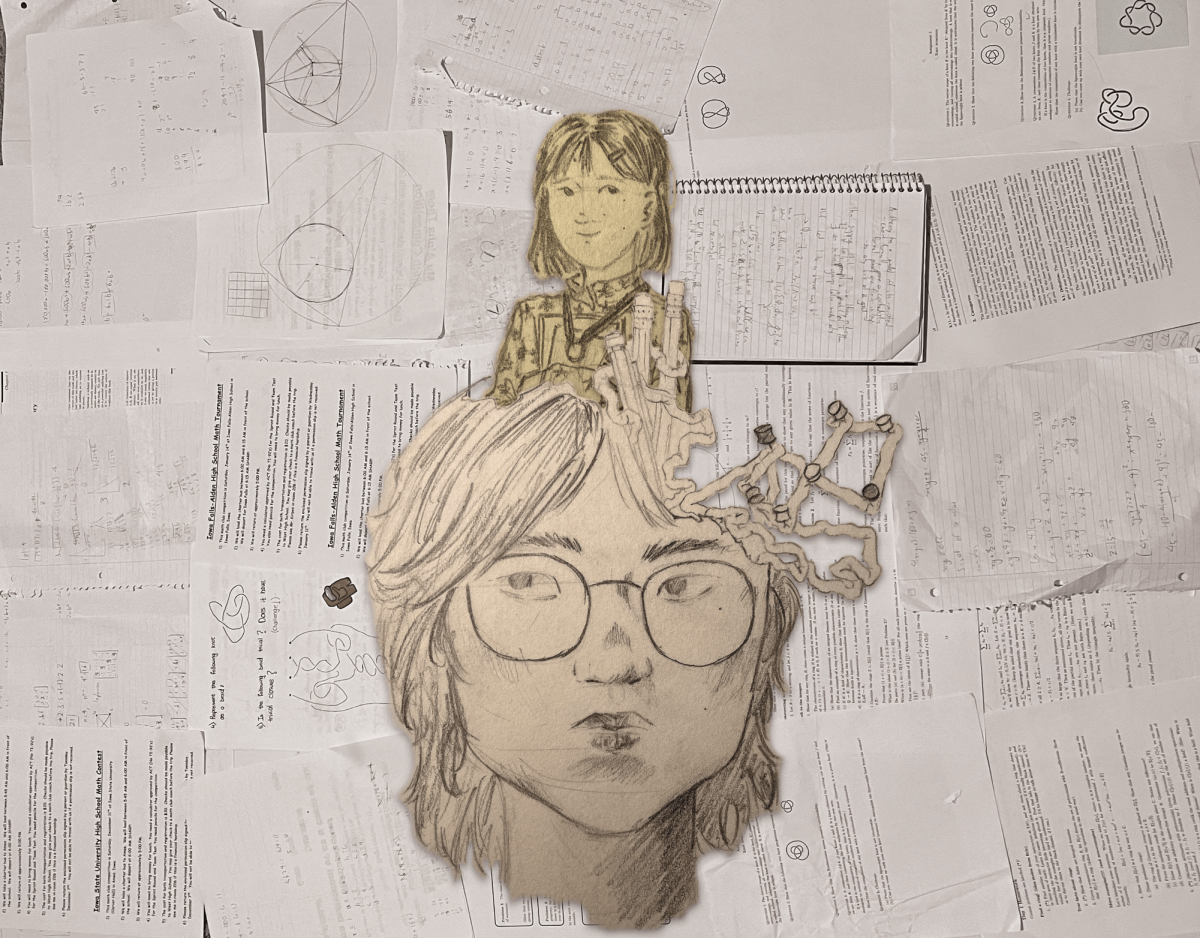

For me, it started in kindergarten.

“Think of the b as a headboard with a pillow, and the e as the middle. The d is the end of the bed. Repeat after me: B-E-D, bed.”

I can’t read the clock, but I know the end of spelling lessons marks the beginning of nap time.

A “Horton Hears a Who!” recording plays from the staticky speaker. Five-year-olds scramble to grab the best blocks, markers and animal figures. Someone trips over their shoes. No one can help them now. I certainly won’t. It’s everyone for themselves when it comes to choosing toys. I snatch the best ones, the green dinosaurs, and run to my blanket. But then, I’m stopped.

“Marie, go out to the hallway. You’re going to be doing something fun today.”

There, on the dusty floor, the geniuses met. A brief image of the geniuses: three kindergarteners — one picking their nose, another repeatedly ripping their velcro shoes and me, scratching my name into the linoleum. What made us geniuses? We could count past 20. I was five, yet I knew it then; we were different.

It happened again the next year; a teacher I had never met took me out of my first-grade class to join a few others —maybe even some who tied their shoes — in the library. There, we did “extension projects” like making a slideshow about our favorite animal — I chose frogs. The next year, I went to another classroom to solve logic problems and sudokus. Then, I was in a book club — a reading group meant for collaborative learning — by myself because I could mutter quickly on a timed comprehension test.

A spot in ELP, the Extended Learning Program, was one of the pinnacles of elementary pride. A spot in that class was like holding the coveted spot of King in 4-Square or being the fastest runner at recess. And, like most of my classmates, I wasn’t in ELP. Though I participated in extension projects, I was not an “ELP kid.” Each time I watched someone walk out to the separate classroom, something in my heart faltered.

Then, suddenly, I was in.

A recommendation, alongside a qualifying Iowa Assessment score, permitted me into ELP during third grade. When I got my letter in the mail, when I got to prove myself, when I got to leave class too, that’s when I knew I made it.

As I left the standard curriculum — as well as my peers — I separated myself both physically and in my identity. Now, I was an “ELP kid.” This separation continued: I passed the fifth-grade test into Algebra I, propelling me into accelerated math. From there, my peer group got smaller and smaller, coinciding with more and more honors and AP offerings. Even now in high school, I receive emails from our school’s ELP program — a program I was admitted into based on my third-grade capabilities.

ELP, and other tracking programs, were created to provide opportunities to stimulate students who weren’t challenged by the core curriculum. These methods begin as early as kindergarten, for example, when five-year-olds join a “special” math club. These programs persist through high school, supplying additional resources to students who passed a test almost a decade prior. Though seemingly helpful, these programs can cause more harm than good, even to students who appear to benefit from them.

My third-grade standardized test score — one I hope to separate myself from now — launched me into ELP. The score brought me higher level math and reading, fun hands-on school projects and additional resources, while all those opportunities should have been provided to students without access. Students who struggle to engage with coursework are the students who would most benefit from extension projects that focus less on routine tasks and rote memorization, and instead personal engagement and collaboration.

Tracking often excludes minority and low-income students from the resources offered by acceleration, instead providing disproportionate white and affluent representation in rigorous or accelerated course work. Separating students who need opportunities more than their white and affluent peers tacitly divides students into two categories: smart and not smart. These categories harm students assigned to lower tracks by needlessly allocating resources to a select group of students, and therefore withholding access to resources and experience from others. By keeping these opportunities from students who need them most, tracking perpetuates educational inequities, which reduces achievement in and out of school.

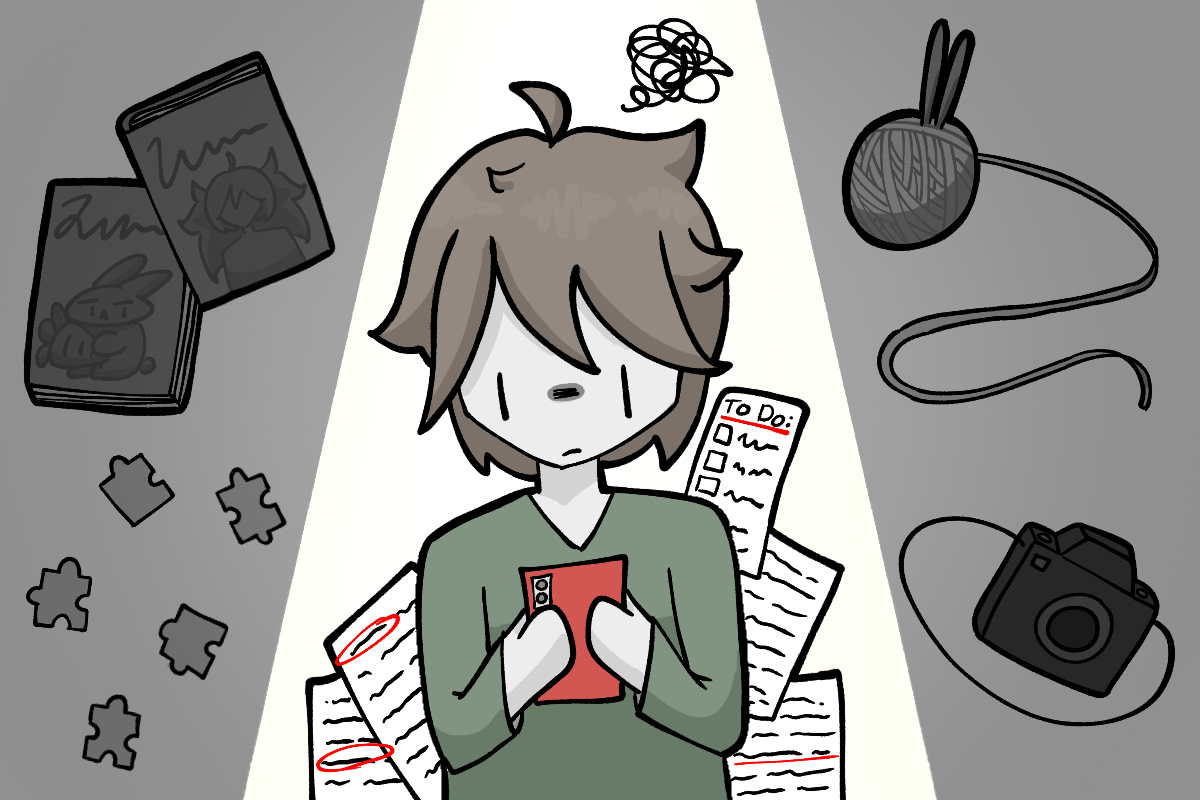

Tracking also harms students assigned to accelerated paths. Accelerated students, because of their assignment to a “better” class, have heightened expectations which, when they fall short, challenge their very identity; if I am supposed to be smart, why can’t I solve this problem? Understand this concept? Rather than an opportunity for growth, problems become displays of shortcomings which gradually result in burnout, inhibiting high-achieving students from developing healthy learning habits and mindsets.

“Gifted-kid burnout,” an internet term which refers to students who were accelerated early in school only to lose motivation and efficacy as they grow older, was coined by students and teachers who recognize the prevalence of these experiences. In a study done by psychologist Carol Dweck, she found that praise centered around ability increases the likelihood for them to develop fixed mindsets — the belief that intelligence is an innate ability one either possesses or does not. Instead, when the children were praised for their effort, they exhibited stronger resilience and developed growth mindsets — the belief that intelligence is malleable. ELP and other tracking programs implicitly — and sometimes, explicitly — tell students they are simply “smart,” and consequently, others are “not.” On both sides of these labels, students are more likely to have fixed mindsets, hurting them in the long run.

The idea of tracking is not to blame; it is important to address the individual needs of students. However, where tracking falls short is in its execution. Gifted and Talented programs like ELP are state-mandated services to students. In my experience, the ICCSD has done a great job of providing quality enrichment opportunities through their ELP programs, but it’s just that: my experience. I am incredibly lucky to have resources from my home in addition to school resources. I am incredibly lucky to be part of the white and affluent demographic which is most benefited from Gifted and Talented programs. I am incredibly lucky, but my experience is not the norm, and it is certainly not the experience of someone in most need of support and enrichment.

The Iowa Department of Education outlines gifted and talented children as “children who require appropriate instruction and educational services commensurate with their abilities and needs beyond those provided by the regular school program.” What student, especially those underserved, isn’t deserving of appropriate instruction and services based on their needs?

To do this, schools should utilize differentiated instruction — a practice focused on providing extension opportunities within the general education classroom — so engagement opportunities can benefit every student. The primary goal of Gifted and Talented programs should mirror the ICCSD Extended Learning Program goal to “expand services to reach more students from underserved populations,” by broadening the recipients of such programs. By extending these programs to all, schools will be extending learning for all.