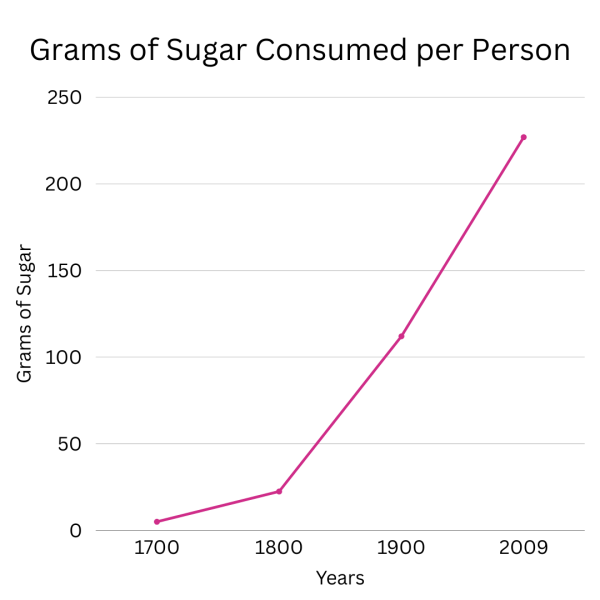

As you walk through your local grocery store, you’re surrounded by a plethora of choices. From savory chips to sugary donuts, all these options seem appetizing. However, the mesmerizing packaging and advertisements distract you from the added sugars and unpronounceable ingredients in these products. Oblivious to the potential harmful effects, you place the items in your cart.

This is the typical grocery shopping experience for many Americans — drawn by appealing marketing without considering the consequences of their consumption. According to the American Heart Association, the average American consumes 70.13 grams of added sugar each day, while the recommended amount is 36 grams for males and 25 grams for females.

Dr. Linda Snetselaar is a registered dietitian, nutritionist and a professor at the University of Iowa College of Public Health with an extensive background in epidemiology, endocrinology and internal medicine. She has also served on the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans Scientific Advisory Committee. Her time on the committee involved investigating several aspects of food consumption, one being excessive sugar consumption.

“One of the things we looked at was the effect of added sugars on chronic diseases and mortality,” Snetselaar said. “Added sugars play a prominent role in the increase in mortality [and] some chronic diseases. We were very clear to the public that added sugars [are] a component of your diet that is not positive. What we found in looking at all of the data available was that it’s one of the more negative aspects of our dietary intakes.”

Besides the well-known threats of high sugar consumption, the lesser-known impacts it has on cognitive abilities are just as real.

“Sometimes — and there are some studies to back this up — too much sugar can play a role in hyperactivity in children,” Snetselaar said. “Anytime you can cut back on something that might play a role in overstimulation [and] attention deficit, that’s always a good direction to go in. If a label has a lot of added sugar, that’s probably something to avoid, especially [for] children.”

While sugar does have a detrimental impact on one’s health, Snetselaar acknowledges that a holistic view of one’s consumption is a better health indicator in comparison to just one nutrient.

“Over the years, we’ve switched from looking at nutrients in isolation to [entire] food groups, and now we look more at food patterns,” Snetselaar said. “[It’s] been a wonderful change to the way we, as researchers, do things, because it’s more inclusive of everything that’s being eaten.”

Honing in on one nutrient has long affected consumer behavior. Much of what people choose to eat is dictated by diet fads focused on specific nutrients. Jana Warning has been teaching Family Consumer Science classes for 15 years and has witnessed diet crazes, like the low-fat diets.

“Every decade tries to villainize a different nutrient. Growing up as a kid in the 90s, it was fat,” Warning said. “Fat was horrible; everything had to be low-fat. To replace [the] fat, [companies] loaded things up with sugar and salt to make it taste good, because fat has flavor.”

However, this substitution attempt came with an even worse setback: nutrient imbalance.

“We learned that’s not an easy or perfect replacement. You’re overloading yourself [with] one nutrient and missing out on the benefits of good, healthy unsaturated fats,” Warning said. “However, one nutrient isn’t [inherently] bad; you need to emphasize balance.”

These diet trends impact not only consumers but also the scientific community. Snetselaar notices how a new food trend can easily attract scientific investigation, which pauses research on older trends.

“I’ve been a part of many National Institutes of Health study sections; it used to be [that] saturated fat was the demon, [but] now, the studies are looking more at olive or avocado oil,” Snetselaar said. “That doesn’t mean saturated fat isn’t still important, but it’s more on the back burner. You’re seeing much more research in the area of monosaturates, and often paired with that is a lower-carb diet.”

As this research evolves, it becomes the building block for many public health initiatives.

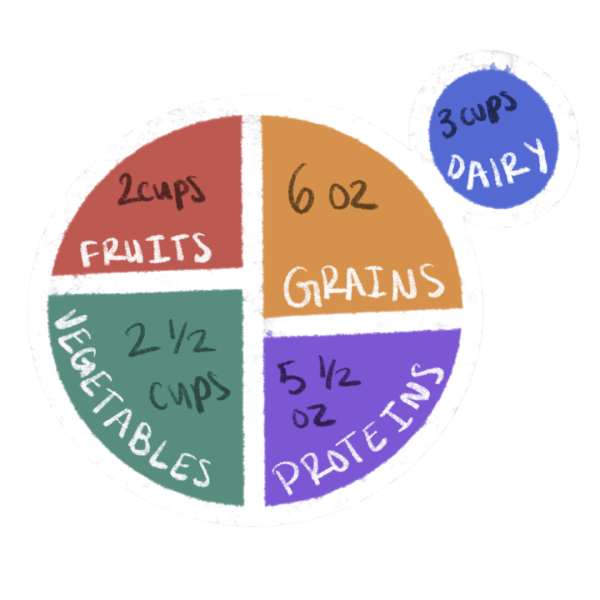

“It’s super important that eating healthy becomes a policy so everyone does [it]. The way it’s presented can make a huge difference in terms of whether or not a policy becomes commonplace for a population,” Snetselaar said. “At one [point in] time, dietary guidelines were presented in pyramid form and were much more connected to numbers: number of ounces or number of cups. What they’ve learned is that people remember very simple things, and if there are too many numbers attached, it’s harder to remember.”

Policymakers took notice of this, and in 2011, the USDA replaced the Food Pyramid with an updated version: MyPlate.

“MyPlate is a picture of a plate with four different regions [and] a glass for dairy. Making sure it’s simple and easy for our population to understand [makes it] much more likely to be adopted by that group of people trying to do a better job of eating more healthily.”

MyPlate is a government initiative overseen by the Department of Agriculture, representing the recommended portion of each food group. The model is a more scientifically accurate plan compared to its predecessor, the Food Pyramid. MyPlate accounts for culture, budget, body weight and height.

The new design of MyPlate emphasizes a base of critical nutrients while not demonizing added food groups. This is reflected in Warning’s belief that moderation trumps elimination when maintaining healthy eating habits.

“We focus on getting your main nutrients [through] those MyPlate groups. We like those higher-sugar foods in our diets, but they’re mostly empty calorie foods. They’re not counting towards our nutritional requirements as much as others,” Warning said. “I look at it as a diet that you can sustain long-term [when] you moderate intake and balance it out day-to-day. [You can] make little adjustments in your diet throughout the day; if you have one day [where] you ate [a lot of] sugar, maybe the next day, be aware and rein it back in. It’s easier to maintain that type of diet versus cutting out sugar altogether.”

Dr. Erin Bergquist, a dietitian and clinical professor at Iowa State’s Food, Science and Nutrition Department, works with patients to help them balance their diets and prevent illness. She cites inaccessibility to proper health care as a reason for many unhealthy diets.

“We’ve got a lot of evidence that shows that if you can meet with a registered dietitian when you’re pre-diabetic, you can prevent [it],” Bergquist said. “What if everyone could see a dietitian and it’s covered by insurance? I can go to a chiropractor as many times as I want for $15 each time; why can’t I go to a dietitian? Greater accessibility to people who have been trained to help prevent disease [can] be helpful.”

To prevent diseases and to promote a healthier lifestyle, Jake Weiler ’28 — a varsity cross country and track athlete — aims to consume consciously. Weiler makes a habit of consistently eating whole foods as opposed to ultra-processed foods to improve his energy, recovery and boost his performance.

“When I first did cross country, I realized I’d have more energy and feel better for workouts [by] eating healthier. When you eat unhealthily, it takes a toll on your energy levels and how you feel throughout the day,” Weiler said.

However, information from initiatives like MyPlate often reaches a limited audience beyond FCS classrooms. Weiler emphasizes the numerous processed options school lunch offers and the lack of information on these choices can make healthy eating difficult for many.

“It can be difficult because you have all these different options of mostly unhealthy foods in the cafeteria. If they had more healthy options, and they pushed those, then kids would be willing to try those,” Weiler said. “As high schoolers, we’re not exposed to information that tells us the downsides of eating unhealthy. Most kids have an idea that they want to eat healthy, but they don’t know what foods are healthy or unhealthy.”

Bergquist takes a different stance, stating that education regarding processed options is prevalent and popular media is more influential than what is taught in schools.

“What would adolescents listen to? Who’s going to hold more weight? Health class or celebrities, YouTubers [and] influencers that you admire? Adolescence is a time when you’re thinking differently; most brains aren’t fully formed until you’re 25 years old, so even if we had excellent nutrition education, [it’s] still an uphill climb. [However,] that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to provide accurate nutrition information,” Bergquist said. “People should still have a choice of what they consume. There is a lot of nuance; something’s not always all bad, and something’s not always all good. There’s quantity, frequency and so many other things to think of as well.”

Weiler notices social media’s influence, crediting it for his consumption of pro-whole food content on social media.

“On the internet right now, eating a whole foods and unprocessed diet is being pushed quite a bit. I’ve seen a lot of people on Instagram, YouTube and other social media platforms posting about eating unprocessed, healthy foods,” Weiler said. “Those videos first exposed me to learning about eating healthier and pushed me towards a healthier diet.”

As teenagers decide whom to trust online, they also have to choose what to load up on, moderate or cut. Warning believes the choices students make now will start a series of habits that can continue into adulthood.

“Teenagers are given more independence in their choice of foods,” Warning said. “If you’ve not been allowed to have a lot of sugar [or] snacks, and now you’ve got a little money in your pocket, you can go to the cafeteria and pick out what you want. Of course, you’re going to gravitate towards those items, but it’s important to understand the habits you’re building and what you are getting out of them [nutritionally]. It’s a unique time in life to be making your own choices and start developing some of those healthy habits versus trying to do so later down the road.”

Weiler chooses to steer away from processed school lunch options and instead towards a diet consisting primarily of whole foods.

“For lunch, I try [not] to eat chips or cookies. I try to [eat] whatever the school has, which isn’t the healthiest, but most of the time, you can get a healthy option in the cafeteria. Then, for dinner, I usually have eggs, chicken or beef. I try to get protein and hydrate [through] milk and water,” Weiler said.

Weiler’s preference for milk and water differs from the national trend of children consuming high levels of sugary drinks, who, on average, consume 30 gallons of sugary drinks a year. Part of this statistic comes from drinks that are usually deemed as “healthy,” such as fruit juices. Snetselaar urges people not to be misled by the labeling of many children’s drinks.

“One worry [is] that a lot of children are drinking juices that, even though they’re labeled let’s say [as] apple juice, have a lot of added sugar. In [the] young age group, they’re getting a lot of empty calories in beverages [with] lots of added sugar in [them],” Snetselaar said.

Along with sugar, there have been concerns about the use of food colors and other chemicals in ultra-processed foods. With these foods being marketed to and consumed by children, lawmakers have begun enforcing stricter regulations.

“There’s been a decent amount of literature that links food dyes [and] artificial flavors to hyperactivity and other sensitivities. California [has] banned [six common] artificial colorings in their school meals. As we look at the science, it does show some concern. I think ‘Why risk it? Children are a vulnerable population,” Bergquist said. “I always try to err on the side of caution. We have these good, healthy foods, we don’t need to add artificial dyes.”

Bergquist’s question of “Why?” is best answered by looking at the psychology of consumer behavior. Consumers gravitate towards foods that are visually appealing because humans tend to first eat with their eyes. Besides food cosmetics, food companies also put a heavy emphasis on marketing to increase sales. In 2022, food companies spent $16.5 billion on advertising. Their tactics range from celebrity endorsements to increasing precision in their marketing by collecting data to target specific populations.

“Businesses will market their product to their target audience,” Bergquist said. “If it’s a cereal that’s brightly colored and has [a lot of] sugar, their target audience might be a child. They’ll do a cartoon character, a catchy [song] or they’ll always show a popular star; something that’s fun that kids can relate to. It’s very effective.”

Sometimes, entire regions fall victim to targeted advertising. The effectiveness of these tactics heavily influences consumers’ choices and can often dictate the diets of millions. This poses a risk to public health as citizens struggle to decipher the actual nutritional value of heavily marketed foods.

“A lot of the drink companies have a strong presence [in Central America]. I’ve read some articles about how even healthcare providers associate Coca-Cola as a healthy drink because it’s been marketed as such in those areas,” Bergquist said.

In an effort to raise awareness to this threat, Snetselaar urges buyers to question a product’s marketing heavily before making a purchase.

“We should always look at marketing with some skepticism because their goal is for [their] company to make money and sell lots of their product,” Snetselaar said. “You’re not going to hear about any of the negative effects of a product, so watching out for marketing where they’re making very blanket comments about a product is important.”

Bergquist sees the solution to be more aligned with policymaking. Her international work in Europe and Africa exposed her to international food advertising regulations.

“Policies that make a difference tend to be marketing. Do we allow marketing to children? Do other countries allow marketing to children and the marketing of some of the unhealthier food products? Policy does help drive what’s available in a country,” Bergquist said.

Alongside marketing regulations, a region’s food availability strongly influences citizens’ diets. This is impacted by climate, culture and landscape.

“Every region has differences [and] nuances in what they eat,” Bergquist said. “For example, when we travel to Ghana into the rural areas, [they have] traditional diets where they eat more whole foods. Their [diets] are based on cassava or maize, [crops] they can grow locally. Those diets tend to be very healthy. When they transition to more urban areas, they have more food available and less land to grow their own foods. Then, the quality of their diet changes, and it becomes [closer to] those processed foods.”

All these contributors to a population’s health influence the work of policymakers, educators, economists, healthcare professionals and more. Bergquist and others in her field categorize these factors to simplify them.

“If you think about how people make food choices, it’s based on a couple of factors. It’s based on what’s accessible, what’s available, what’s affordable and then [what’s] appealing. We call them the four A’s.”

As professionals utilize these factors in their work, they can help shape the food climate to be filled with nutritional value and promote healthy lifestyles. Questions asked by these professionals apply to the wellness of everyone.

“What does it mean to have a resilient food system that’s economically viable for everyone, from eaters to producers, all along that supply chain?” Bergquist said. “How do we do it in a way that preserves our natural resources and meets our quality, diversity and safety [standards]? What foods can we grow in Iowa that are nutritious and health-supporting that meet those principles of sustainable food systems?”

As professionals ask themselves these questions, consumers should do their part and stay cognizant of their diets.

“It’s all about finding that balance that works for you [by] making sure to include all food groups, to get a variety of nutrients, and understanding that your nutrition has an impact on your health,” Warning said. “Make decisions that are going to make you feel your best and lead to the best possible health.”