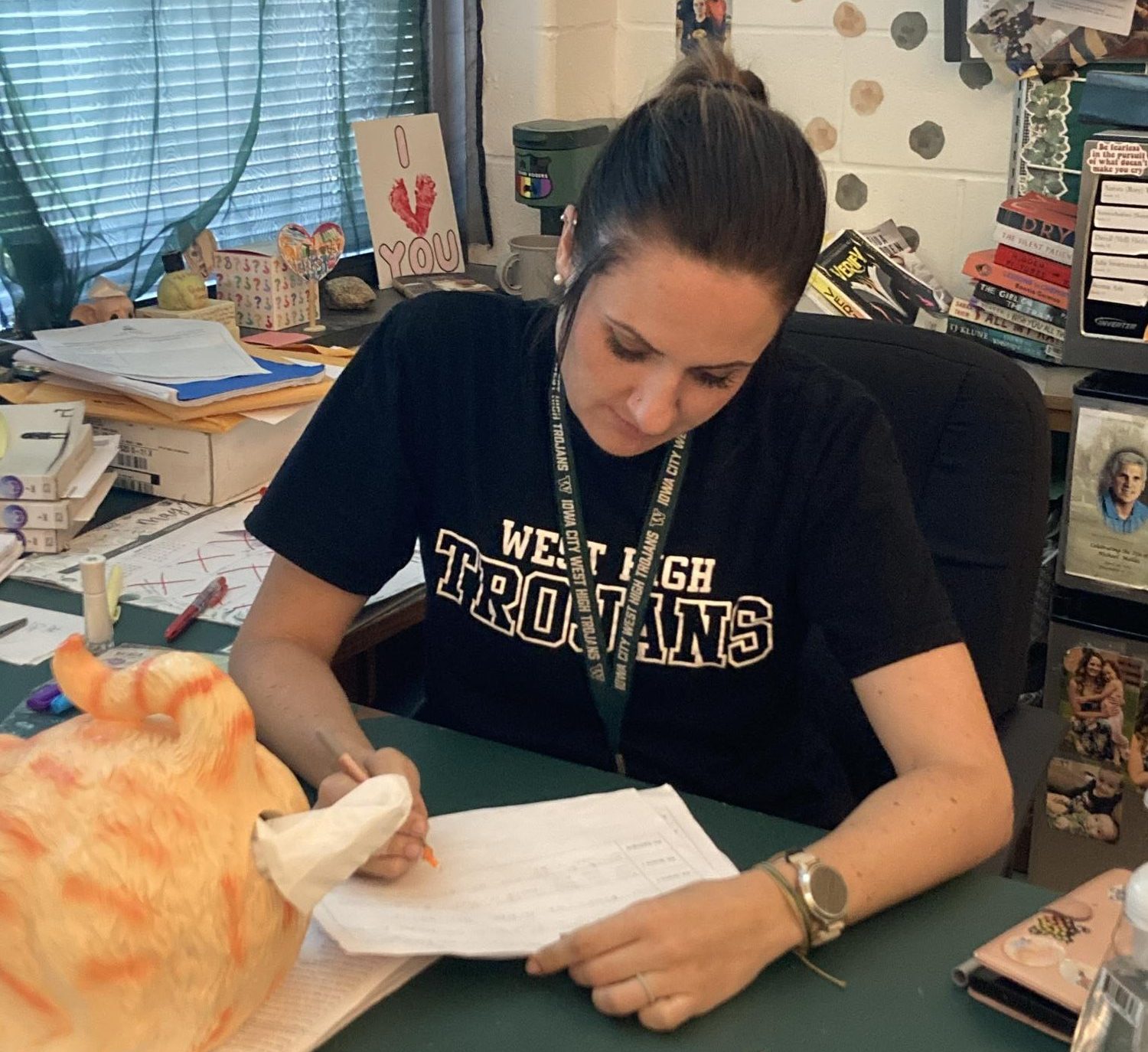

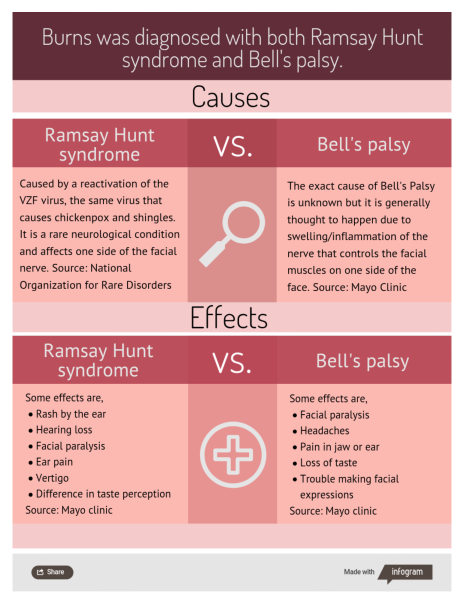

Traci Burns, West High English teacher, has not always had it easy. While in college at the University of Iowa, she was diagnosed with Bell’s palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome, causing her to drop out of school to recover. But that didn’t stop her from achieving her goals, no matter how hard life got.

While in college Burns was a go-getter, loading up on classes and accelerating her education. Her dream was to become an English teacher and she wanted to get in the classroom as soon as possible.

“I just loved being a student, and I love learning. You’re only supposed to take 15 credits, and you can max out at 18,” Burns said. “I got special permission to take 19.”

While taking classes, Burns also worked as a preschool teacher and was often sick because of it. These factors combined led to unhealthy amounts of stress which contributed to her eventual diagnosis.

“One of the reasons why people get shingles is because of stress. And so I think the [sickness] was just my body telling me that I needed to take a second and take care of myself,” Burns said.

Burns began experiencing pain in her eardrum a few weeks prior to her diagnosis but initially chose not to seek help. Three weeks after she started feeling symptoms, her face went numb, and paralysis set in. As it got worse, Burns grew increasingly worried, calling a friend to sleep over and take her to the emergency room the next day.

“I had always had ear aches as a kid, but this was different, because it would interrupt me in conversation, it would be so painful that I had to stop [speaking],” Burns said. “The night before I was [diagnosed], my face went paralyzed. I remember I was eating eggs, and I couldn’t taste them, and I was like, ‘this is really weird.’”

Burns experienced severe vertigo, pain and facial paralysis, leaving her bedridden.

“It made everything come to a complete stop. And I was so sad, because everything I had been doing up until that point was to get me in the classroom, working with students,” Burns said.

Originally Burns tried to remain in school, working remotely from her dorm. She quickly realized, being so highly medicated, she couldn’t function without help, and she made the decision to drop out for the rest of the semester.

“There was a lot of fear, because I didn’t know when my body would allow me to kind of return to my [normal] activities. So I ended up moving back in with my parents for the entire semester, and going back to school that summer,” Burns said.

Burns’s condition was much worse than she had imagined and recovery took longer than expected. Being in pain for so long left Burns wondering if she could ever return to school or become a teacher.

“The paralysis is supposed to go away within about two weeks. Mine, my face was entirely paralyzed six months. I was just like, ‘Oh my god. How can I be a teacher?’” Burns said.

Being a student and working towards being an educator was a huge aspect of Burns’s life, so not knowing if she would ever be able to return to her dream of becoming a teacher was the most terrifying aspect of this experience for Burns.

“When you’re in the thick of it, and you’re in the thick of it for so long, it’s like, ‘Will I ever be able to return?’” Burns said. “I lost my identity, and I didn’t know if I could keep my same goals.”

Having her life stopped soon took a mental toll on Burns. Her facial paralysis and isolation from her friends plunged Burns into depression as she tried to navigate her changing body image and identity.

“It was a very, very dark time for me. There was a lot of self hatred like, ‘Why would my body do this to me?’ Burns said.

It was only after Burns had worked through her feelings of anger she realized her body was not to blame.

“My body didn’t do it. My body saved me, probably because I was just going at too fast of a pace. I wanted to find something to blame, but really, it was my own choices,” Burns said.

When Burns eventually returned to school and joined the classroom she found her experience taught her more about mental health struggles. She now uses what she’s learned to help her students and improve her classroom atmosphere.

“Having gone through the process of experiencing depression and then being treated for it, that was very eye opening to me,” Burns said. “It really helps me relate to my students in a very different way, because I have plenty of students who have mental health struggles, and although I don’t know their exact situation, I know how complicated it is.”

Fitting with her upbeat personality, Burns turns her still slightly paralyzed face into an introduction for her students. For her, mentioning her condition before students ask, helps her feel more comfortable with herself and her face.

“At the beginning of every school year, I ask students, ‘what are their idiosyncrasies,’ and I kind of make fun of myself with it. I say it, I name it, it’s out there, so I don’t have to feel as self conscious about myself when I can feel my face is not moving in the way that it should,” Burns said.