Working toward peace

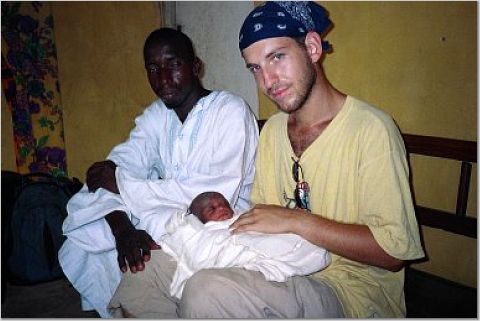

Social studies teacher Alexei Lalagos has traveled extensively around the world, creating experiences that have shaped how he lives his life.

February 18, 2017

After hitchhiking to “save a couple bucks” and huddling in the back of trucks with a buddy from the Peace Corps, social studies teacher Alexei Lalagos made it to Agadir, Morocco.

This was part of a three-month expedition in which he also traveled to Northern Senegal and Tunisia, encountering multiple incidents of jumping of truck hopping.

“The driver [of the truck] got sick on the way [to Agadir], so he sold us off to another driver,” Lalagos said. “Looking back, it was a little sketch.”

His drive to explore the world was instilled in him at a young age, as Lalagos is a first-generation American. He attributes his love of socializing to his upbringing by a Greek father and a Cuban mother.

“Both of my families come from cultures surrounded by food. And they’re both loud. I like that kind of chaos,” he said.

In search of good food and social justice, Lalagos has been traveling his entire life. He first left the country for Greece when he was three years old, and has since traveled to over 20 other countries.

This wanderlust inspired Lalagos to join the Peace Corps after completing his undergraduate degree. He was placed in The Gambia, and spent his first ten weeks immersing himself in the culture to learn the local dialect, Fulani.

“[Lalagos] has always seemed to have an inner drive to help people and leave a positive impression on the world,” said Lalagos’ friend Shawn Hansen. “I feel that this drive, combined with his passion for travel and exploration, led him to join the Peace Corps and spend those years in The Gambia.”

Lalagos’ ten week designated acclimation time was also used to begin to understand the cultural differences.

“People do not stay inside at all in [The] Gambia. If you’re inside, you’re either sleeping or you’re sick,” he said. “We had this negotiation of like, hey, if I’m in my hut doing this or whatever, you can’t just barge in.”

The idea of what exactly constituted as property was especially different in The Gambia. Just because something was yours didn’t mean someone wouldn’t just take it for a bit without telling you, and if something was gone, chances are someone may have “borrowed” it.

When he wasn’t searching for things that others may have “borrowed”, Lalagos was teaching classes to children. The Gambia is a former British colony that gained independence only 38 years before Lalagos arrived in 2003, so all of the classes he taught were English.

Lalagos also played guitar, wrote journals and letters and says he “read more in those two years than in [his] entire life.”

After completing his time in The Gambia, Lalagos attended night classes at DePaul University to attain his masters in secondary education with a focus on social science. While back home in Chicago, he met his wife.

His wife, Marina, is originally from Ukraine, and helps foster Lalagos’ desire to explore the world. In fact, one of Lalagos’s scariest memories involves him taking her on a trip to The Gambia.

That trip was far from being a smooth sailing romantic getaway, and included a stint of getting stuck at the Senegal-Gambia border.

“We’re at the border, and they say something [like] ‘make sure you don’t go back over,’” he said.

They gave that warning because unknowingly his wife had one entry to Senegal on her visa, which they used when she landed.

Eventually, with some impassioned French discussion, Lalagos and his wife were able to fly from Banjul, Gambia, back to Dakar, Senegal. They stayed in the vicinity of the hotel, slightly outside of Dakar, and did “the refugee kind of thing” by playing cards and not going to the center of town with the fear of her getting her papers checked.

Naturally, Lalagos proposed to her the day they got back to the States.

“After that experience I was pretty sure I wanted to spend the rest of my life with him—in case I ever get stuck on some other border again,” said his wife Marina Zaloznaya.

Lalagos and his wife hope to instill the same passion and appreciation for the world they grew up with in their kids.

“Positive encounters with those who are different from us builds tolerance, critical thinking, and intellectual curiosity. In these times more than ever, as a society, we need citizens who have these skills,” Zaloznaya said.