Fading tongue

Losing the language of your heritage can leave room for regret — but that doesn’t mean you should be any less proud of your culture.

Helen Zhang ’23 discusses losing her native tongue.

I still remember the absolute dread I felt every Saturday from age 6 to 9. I wanted to do anything but take part in a weekly occurrence I felt forced into: Chinese lessons. Every weekend, my brother and I would spend around two hours learning the language, either from our parents or our parents’ friends, whose children learned with us. I often dreamed about watching cartoons or going to a birthday party instead, and during each lesson, I would count down the minutes until I would finally be free. It wouldn’t be until several years later that I realized how much I took those lessons for granted.

I am what is known as a heritage speaker: someone who has learned a language informally by being exposed to it at home. Like many heritage speakers, I am a child of immigrants, as my parents moved to the U.S. from China before I was born. Since I was a toddler, I have spoken Mandarin Chinese with my family, and in my earliest years, I was at least equally fluent in Mandarin as I was in English. Unfortunately, my fluency and comfort with speaking Chinese have weakened over the years, and most days, I don’t utter a word of it. The process of losing one’s first language is called language attrition, and issues associated with it include forgetting words, becoming hesitant and developing a foreign accent.

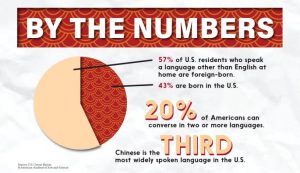

This experience is not unusual for immigrants and their descendants. According to Pew Research Center, as of 2018, 17% of U.S. immigrants ages 5 and older only speak English at home. Additionally, as of 2017, 32% of Asian Americans only speak English at home. During both the past and present day, the pressures of assimilating to American culture and English-only rhetoric have been prominent factors that lead foreign-language speakers to prioritize English as their primary language.

For me, Chinese simply became less of a priority. After the third grade, my family stopped lessons because my brother and I became occupied with other extracurricular activities. At the time, this change was a relief. Now, I’ve come to terms with the fact that it had a detrimental effect on my ability to speak the language. I rarely practiced reading or writing it after that and never became literate. I was more comfortable communicating with my parents in English and became less and less used to speaking Chinese. It was a vicious cycle: as I continued to use Chinese only minimally, I lost my fluency, resulting in my stronger preference for English. Even though my parents continue to speak to me in Chinese, I usually reserve speaking Chinese for my extended family, mainly my grandparents.

Sometimes during a conversation, I forget how to say a word or phrase, and I immediately regret not working harder to learn Chinese. Because of this, our conversations feel strenuous and one-sided at times. My grandparents will ask me about my life, and I will provide short, simple answers but cannot ask them much about theirs. Lacking fluency has made it harder for me to form a close relationship with them.

However, my relationship with my grandparents has shown me that my minimal fluency does not define my connection with my culture. One of my favorite activities I get to do with them is cook, and I’ve learned a lot from them about making dumplings, noodles and other traditional Chinese dishes. During our time together, my grandparents have also told me stories about growing up and living in China. I remember my grandmother telling me about going to school as a child and showing me a style of Chinese dance that she loves. Just listening to them has taught me so many wonderful things about my culture, and spending time with them has been extremely valuable. Even if I can’t say as much to them as they say to me, expressing my interest in the things they share can show how much I love them just as well as words.

Still, there is that fear in the back of my mind of abandoning my culture. I am envious of those who are fully immersed in their ethnic culture, including their ability to speak and write in their other language perfectly. Am I just lazy for not taking the time to learn Chinese? Is it too late to try again?

I do have some responsibility for how much I practice the languages I speak. I could have made a greater effort to speak Chinese at home and found ways to expand my vocabulary instead of leaving it very limited. But I shouldn’t feel guilty, and if you are in a similar situation, you shouldn’t either. According to the Association for Psychological Science, it isn’t unusual for our brains to suppress our native languages when learning a second one; it’s natural that when speaking multiple languages, one becomes dominant. Although I don’t feel as fluent in my culture’s language as I wish to be, I don’t have to be less connected to it. My cultural heritage is something I always carry with me, and I should be able to take pride in it even if I don’t know all of it perfectly.

Furthermore, it’s never too late to relearn or learn something. Even if I don’t achieve the accent of a native speaker, I can still learn to carry a conversation with someone. The purpose of speaking a language is to communicate with others; perfect pronunciation and grammar are not necessary to fulfill this purpose. I understand the reluctance to learn; speaking a language that’s not my dominant one causes me embarrassment at times, especially when people make offhand comments about my American accent or the fact that most of my family members are more proficient in it than I am. However, some embarrassment is a small price to pay to improve a skill that you strongly want to excel at — whether it’s language or something else. At any age, practicing a new or old language with others and exposing yourself to it will be beneficial.

I don’t know if I’ll ever significantly improve my ability to speak Chinese or learn to write it. Maybe I’ll take Chinese lessons again, either at home or at college. What I do know is that this does not reduce my Chinese identity, and it doesn’t have to hold me back from embracing my cultural heritage and the people that come with it.

Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Helen Zhang is a senior at West. She is the columns editor and this is her second year on print staff. In her free time, Helen enjoys baking, reading and...

(she/her) Sila Duran is a senior at West and it's her third year on staff. Sila is the Print Assistant Design Editor. You can typically find Sila at art...