Stress solutions

Explore the science behind stress, its dangers and benefits, and how some students find solutions.

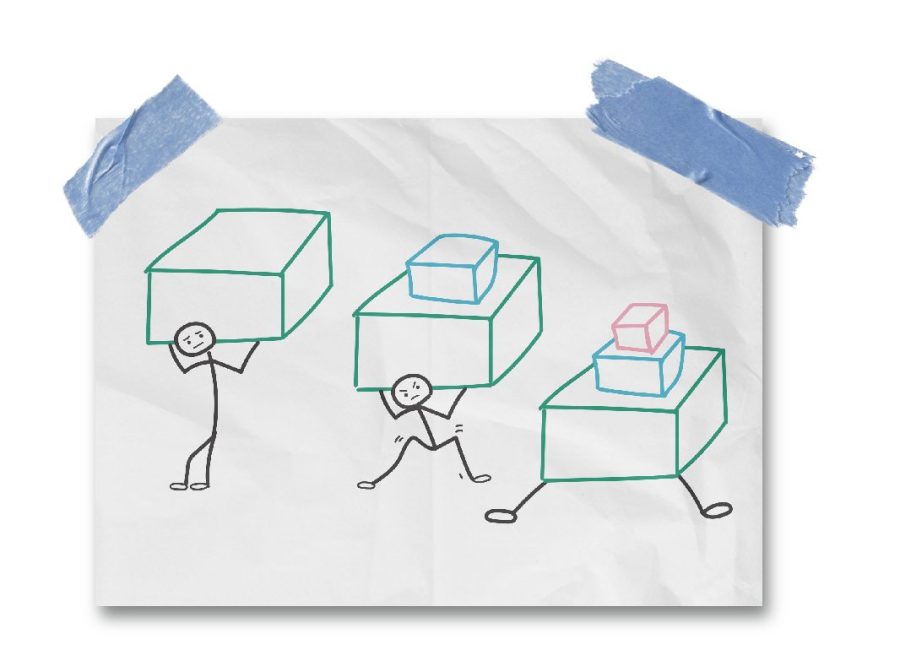

Stress comes from a broad range of sources, with homework and other academic duties being the most common for students.

Math class made no sense. You stayed up late studying, and the lack of sleep made focus impossible. Upcoming tests ensure that you will need to put in hours outside of class to catch up. Feeling overwhelmed, you struggle through conversations with friends and family, unable to get your mind off the assignments piling up. With a defeated sigh, you tensely finish out the day with a job, homework, club meetings or household chores that add more unresolved tension. A day like this is the norm for many West High students, most of whom, while familiar with stress, may not know how to manage it.

Stress comes from a broad range of sources, with homework and other academic duties being the most common for students. In addition to mandatory coursework and testing, some West students attribute their stress to extracurricular responsibilities, the ongoing pandemic, and family or relationship issues.

Evan Zukin ’22 faces many sources of stress.

“I feel a lot of stress on an average week because I’m in a lot of activities. That’s always something that’s on my mind,” Zukin said. “I’ve got to do college applications and homework, and teachers love to lay it on.”

In a recent survey of 75 West High students, 90.7% indicated feeling moderately or very stressed, with just 2.7% reporting not feeling very stressed at all. Despite an abundance of stress, more than half of students reported not having an effective way to manage it. With this strain being so common, it is vital to understand what stress is, its risks and benefits and how to deal with it.

Dr. Jason Radley is a professor in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at the University of Iowa, and his research focuses on stress neurobiology. In an email interview, Radley defined stress as the set of bodily responses to adverse events where the individual cannot predict or control their circumstances.

Chronic stress can be a risk factor for bodily diseases and mental disorders. Stress increases the hormone cortisol that can contribute to or worsen metabolic syndrome — a collection of symptoms that increase disease risk. Research suggests that cortisol, even in the absence of metabolic syndrome, may negatively affect brain structures essential for cognitive and emotional functions.

With its potential health risks and prevalence among students, it is easy to view stress as entirely negative. In truth, stress is not necessarily problematic — it plays a crucial role in human survival and function.

The human stress response has been conserved through evolution to promote survival in adverse conditions. According to Greater Good Magazine of the University of California Berkeley, stress in the short-term can increase alertness and encourage the growth of stem cells that become brain cells, thus improving memory. Heightened memory and attentiveness can help animals remember dangerous situations to avoid them in the future.

“The issue is that severe traumatic or chronic stress can lead to negative health outcomes,” Radley said. “So stress is good under short term conditions but bad under chronic conditions.”

Given the risks chronic stress poses to physical and mental health, addressing it is vital to maintain a healthy life.

“The most helpful thing is to get to the bottom of why one is stressed, and then make changes in one’s behavior — termed coping — that will improve one’s situation or reduce the stress level,” Radley said.

Zukin copes with stress by keeping an organized spreadsheet, a habit he picked up during the pandemic. The Google Sheet began as a place to find his Zoom links, but now back in person, he continues using the document, giving each class a column with course-specific details and responsibilities. He also links the class Canvas page, any assignments and other deadlines.

Zukin has found that consolidating all his work in one place saves time and decreases stress.

“The shortcuts on the document are what help me out because I can get to everything I need from one spot,” Zukin said. “When I’m in my document, I can see what the assignment is, click on it, go right to it and start working on it … it really helps me ease my stress.”

Although maintaining a document like this may seem time-consuming, Zukin argues it is helpful in the long run.

“If I’m keeping up on it, it’s not a hassle at all,” Zukin said. “If I let it get away from me and have to do a bunch of stuff on the document at once, it kind of piles up.”

To avoid pileup, Zukin updates his spreadsheet immediately after receiving or completing an assignment. He recommends having a similar document for anyone who has trouble keeping track of everything.

“I try to keep myself very organized, and that helps a lot,” Zukin said. “On top of the stress of having to do everything, I’m not stressed about having to find it.”

Organization extends beyond keeping track of assignments. Keeping a well-organized living space is often associated with less stress.

According to the Mayo Clinic, cluttered spaces can induce anxiousness. Furthermore, disorganized areas make it harder for the brain to process useful information, hindering the ability to focus. To stay focused, keep a clear desk — and desktop — and set aside a few minutes to organize your workspace before taking on a task.

Adeline Lasswell ’24 copes with stress by keeping a moderate workload and having hobbies to fall back on when they do feel stressed.

“A big part of how I manage stress is managing how much work I take on in the first place,” Lasswell said.

Finding a balance between rigor and relaxation is important for Lasswell.

“I think it’s good to challenge yourself … I take a few honors classes,” Lasswell said. “But if I get a lot of homework or a lot of work, then that kind of adds a lot of stress for me. So I think keeping that workload down is how I manage stress.”

Experts like Radley have found that proactive coping strategies, or controlling a situation before it becomes stressful, can be healthier than reactive techniques, which involve acting in response after a situation has become stressful.

“Proactive [coping] has been shown to be beneficial to our health and associated with better physical and mental trajectories,” Radley said. “Whereas reactive coping is correlated with the usual suspects in metabolic syndrome and higher risk for diseases.”

Nevertheless, Lasswell has found some reactive coping strategies helpful in the short term.

“Sometimes just walking my dog outside for a little bit is a good way to get my mind to calm down,” Lasswell said. “I think a lot of the time when you’re stressed, you focus on whatever the issue is and kind of catastrophize it in a way.”

Lasswell suggests that everybody finds an enjoyable hobby unrelated to school which they can turn to when stressed.

“Having hobbies outside of any school or extracurricular activities is good because when you’re constantly being graded or scored on stuff, then that can take enjoyment out of things that would normally help you relieve stress,” Lasswell said.

Coping strategies vary from person to person, and the most effective ones are typically personalized to best address someone’s stress. Everyone should know when stress may be dangerous and explore strategies to help relieve chronic stress.

“When you do [get overwhelmed], prioritize yourself. Take a step back,” Zukin said. “Do what you can in the moment, but don’t let the stress make it so you can’t do what you need, because then it just gets worse.”

As part of prioritizing himself, Zukin notes getting adequate sleep is one of his most successful, proactive stress management strategies.

“If I’m not sleeping, my brain is not working, and if my brain is not working, I’m not getting stuff done, and then there’s more stress, so sleep is my best friend,” Zukin said.

It is important to remember that the stress response is natural and necessary. Evolution explains why stress is beneficial but also how to deal with it if it becomes a recurring problem.

“Humans have evolved for face-to-face social interaction with one another,” Radley said. “Social support is critical; many of us can’t solve problems on our own. We need help, not only from peers, but from people who have had more life experiences and have overcome adverse circumstances.”

In addition to support through problem solving, social contact and support enhances the hormone oxytocin: a hormone that reduces the stress response.

Those who are very seriously struggling with stress may consider more sophisticated coping strategies.

“Again, social support is key,” Radley said, “but in cases where stress is severe, getting help from an expert or health professional may be needed or the best approach for finding solutions.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Miguel Cohen Suarez is a senior at West. This is his first year on staff; he currently works as a sports reporter for the online and broadcast publication....