Carbon crossroads

The Summit pipeline aims to capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Its proposal has sparked controversy among Iowan environmental activists and farmers alike.

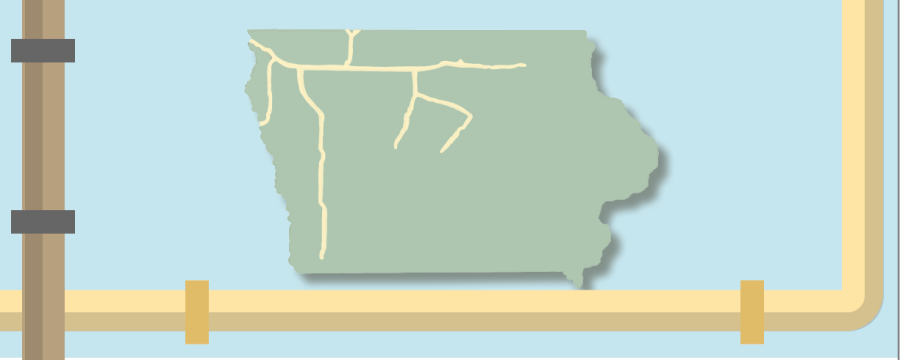

The Summit pipeline would span 681 miles through Iowa.

April 23, 2022

As the effects of climate change become more evident with rising temperatures and increasingly frequent natural disasters, both scientists and companies have devised innovative solutions to reduce fossil fuel emissions. One such solution is carbon capture pipelines, which gather carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, liquify it, then store it underground through the process of sequestration.

Summit Carbon Solutions, a company based out of Ames, Iowa, is currently seeking funding and approval for a $4.5 billion carbon capture pipeline that would span five midwestern states, including 681 miles in northern and western Iowa. The pipeline would capture carbon emissions from ethanol plants that use corn to produce ethanol, a renewable fuel found in motor gasoline. As of press time, the project has yet to be approved by the Iowa Utilities Board.

“This system would have the capacity of capturing and storing 12 million tons of carbon dioxide on an annual basis, which would make [it] the largest carbon capture and storage project in the world,” said Jesse Harris, Summit’s public relations advisor. This reduction in released carbon dioxide would allegedly contribute to the United States’ goal of reaching net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Harris believes the pipeline would create economic opportunities because ethanol developed under more environmentally conscious conditions can sell for higher prices.

“For ethanol producers [and] for corn growers, this is a really significant opportunity in the coming years,” Harris said.

The Sierra Club is a nationwide organization that advocates for environmental conservation. Jessica Mazour is the Conservation Program Coordinator for the Sierra Club’s Iowa Chapter and has spoken out against the pipeline.

“[The pipeline] isn’t about climate change,” Mazour said. “It’s about some very wealthy people making a lot more money. We have strong beliefs that [Summit is] going to use the carbon dioxide for a process called enhanced oil recovery.”

Enhanced oil recovery, or EOR, is when carbon dioxide is injected into oil wells to boost oil extraction, resulting in more greenhouse gas emissions. Mazour believes Summit plans to use the carbon dioxide obtained by the pipeline for EOR rather than permanently storing it underground. In a March 2 article published in the Des Moines Register, Summit Executive Vice President Wade Boeshans denied plans to implement EOR. Harris echoes Boeshans’ statement.

“This project will not be utilizing enhanced oil recovery; I think we can say that definitively,” Harris said.

Harold Hamm, the owner of Continental Resources, North Dakota’s biggest oil drilling company, recently invested $250 million in Summit’s pipeline.

Deborah Main is a landowner from northwest Iowa who has been contacted numerous times by land surveyors seeking to acquire her acreage for the pipeline. Main owns a century farm, meaning her land has belonged to her family for over 100 years. For Main, Hamm’s investment questions the project’s true intentions.

“You’re lining up oil people [to invest],” Main said. “If it were an environmental issue, the oil person would not put one dime into this project.”

Harris holds that investors simply see this work as a way to profit.

“I can’t speak for [Hamm] personally,” Harris said, “[but] I think that there’s a significant opportunity around this in terms of decarbonizing critical industry across the Midwest with ethanol; I think he sees an economic opportunity.”

The pipeline would run through private land, most of which is agricultural. During the construction period, landowners would either have to agree to the pipeline’s development or have their land temporarily taken from them under eminent domain, the government’s right to overtake private land without the owner’s proper consent in exchange for monetary compensation.

Main has taken an active role in opposing the pipeline’s construction and is concerned about how Summit will obtain the required land. If the Iowa Utilities Board determines that the pipeline is in the interest of the public good, Summit would be able to exercise eminent domain.

“[Summit] has a mission to accomplish and they will accomplish it by any means necessary,” Main said. “They want my family’s land, but they’re not part of my family; they don’t belong here.”

Main emphasizes the pipeline’s projected impact on heritage and livelihood.

“We don’t inherit the land from our ancestors. We borrow it from our children,” Main said. “So what are we leaving for our children if this pipeline gets put in?”

Harris believes Summit is unlikely to resort to using eminent domain as of now.

“We prioritize our negotiations and conversations with landowners,” Harris said. “I know eminent domain is a topic that has been brought up quite a bit on the other side, but we’re kind of really nowhere at that point in the process just yet.”

According to Mazour, a bipartisan sense of unity among landowners stems from this possible destruction of farmland and heritage.

“For the most part, landowners have been told to hate groups like the Sierra Club, and the Sierra Club is supposed to hate all the Republicans,” Mazour said. “Yet, when it comes to this issue, we actually have a lot in common. We care about our farms, our soil, our neighbors, our communities — and we’re able to look past those differences and work together.”

According to Main, additional concern centers around how the pipeline could have direct environmental impacts such as soil disruption and crop damage.

“[Pipeline workers] don’t understand what happens when you compact the soil hard enough that you can build a road on it — you can’t grow anything on it,” Main said.

Mazour shares these fears.

“We have major concerns of just what it’s going to do to our soil because it took thousands and thousands of years to create, and it’s what makes Iowa an agricultural state,” Mazour said.

Charles Stanier, a professor of chemical and biochemical engineering at the University of Iowa, was a member of an advisory panel on carbon sequestration for the State of Iowa, and while on the panel, he advocated for greater transparency. Once installed, he questions how Summit and the ethanol plants would record and quantify the pipeline’s impact.

“I think there should be very transparent disclosure agreements for how much [the pipeline] is capturing — how much is going into the pipeline versus was leaked … what’s the monitoring system to make sure that the accounting is appropriate?” Stanier said. “There were crickets every time I said that. People didn’t want to go there.”

Stanier also believes the pipeline’s impact could be relatively minor; his calculations project a 2-3% reduction in Iowa’s carbon footprint. Instead, Stanier thinks the future lies in renewable resources and predicts the pipeline’s utility may eventually become irrelevant.

“I think electrification is going to win in the long term. It will be better off to get ahead and capitalize on wind and solar and make renewable energy,” Stanier said. “Investing in something that’s going to be a falling market — I think it’s a short-sighted approach.”

Mazour also holds the pipeline will fail as a long-term solution because it accommodates nonrenewable energy rather than finding a more sustainable alternative.

“We already know the real solutions to climate change, which are decarbonizing, getting off of fossil fuels, and doing wind, solar, and battery storage,” Mazour said. “If we allow this … we’re just putting a band-aid on an industry that’s already contributing massively to climate change.”