For decades, the state of Iowa has mandated that school boards include programs for gifted and talented students. To comply with the state mandate and help these students excel, the ICCSD created the Extended Learning Program, designed for academically gifted students in elementary, middle and high schools.

Students can test into the program in elementary school following eligibility identification through a teacher, score nomination, or parent. Testing begins in second grade, with scores from the Cognitive Abilities Test and Iowa Statewide Assessment of Student Progress. Students do not have to re-test each year after acceptance into the program.

Once accepted into the program, students engage in a challenging curriculum, combining various units of study that involve higher-order thinking skills. Additionally, students participate in special interest groups or individual studies and meet with their designated ELP teacher outside of the typical classroom. At these meetings, students are intended to receive the academic guidance and counseling they need to succeed, as well as career counseling and exploration opportunities.

Identification

Claire Chapnick is an Elementary ELP teacher at Coralville Central Elementary and Kirkwood Elementary. Chapnick’s responsibilities include hosting meetings for groups of students in grades three through six and managing enrichment, the advanced path for kindergarten through second-grade students. Screening for enrichment starts at the beginning of the year and consists of lessons that are designed to recognize gifted students, district assessments and teacher notes. Similar to ELP, students are recommended for the program by their teacher and are given district reading and math assessments to test for proficiency. “It’s been changing, but the main idea for ELP identification is teachers rate students on various gifted characteristics, and we look at ISASP scores,” Chapnick said.

In addition to ISASP, the standard assessment test, ELP also gives an above-level assessment, which has previously been the CogAT. “That’s changing as well, but in general, it’s an assessment to recognize gifted learners and it has three components. Verbal, which is language, and vocabulary, quantitative which is math, and then what’s called spatial or nonverbal reasoning, sort of spatial relationships and patterns,” Chapnick said. “So, to qualify for ELP, in the past, what it’s been is a blended score between the score on the verbal reasoning test, the score on ISASP and teacher points.”

Curriculum

Chapnick hopes that the ELP curriculum “engages students and has them excited about studying at the level where they are.” One of ELP’s main goals is to give students exposure to a variety of subjects early on. “If students are engaged in an early age, and are introduced to a number of subjects that, if they have an affinity for it, later in their educational career they take to a higher level,” Chapnick said. Apart from academics, ELP emphasizes social and emotional learning. The program allows students to form close bonds with their peers and make long-lasting connections that can teach these concepts. “I believe that we’re all social creatures. And one thing that makes school fun is if you have connections and if you have friends. And most importantly, if you’re happy, and so to me, if they’re in ELP, and they’re excited about learning and making friends with their peers, hopefully, that feeds into helping them like school and be excited about school. And when you’re happy and you have friends, then you perform better, and so, hopefully, do better academically, too,” Chapnick said.

Because ELP class sizes are significantly smaller than regular classes, teachers can better address any challenges students may have. On the flip side, students can feel more comfortable speaking up in a smaller environment and better navigate their emotions.

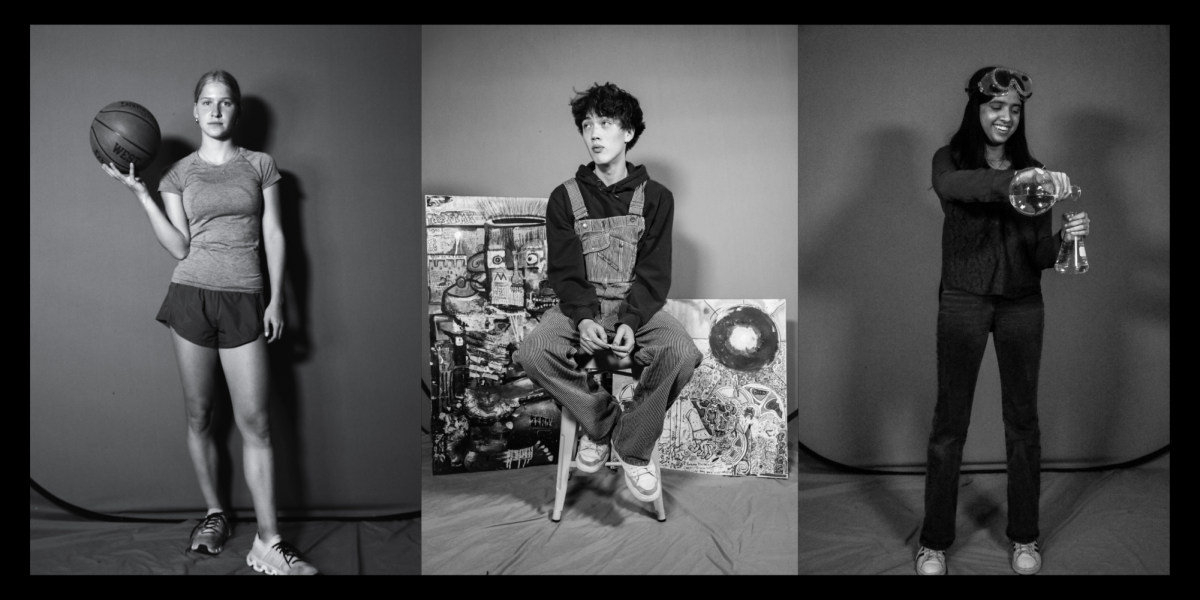

Chapnick’s belief that ELP not only helps students academically but also socially, seemed to make an impression on one of her former Coralville Central Elementary students, Greyson Reed ’25. Although Reed, who participated in ELP from grades fourth through sixth, sees himself as always being a social person, he still acknowledges the positive effects ELP has had on his relationships, particularly when it comes to group projects.

“I’ve always felt pretty social, but there was definitely a lot of collaboration [in ELP],” Reed said. “I didn’t really like doing group projects [previously], because I’ve always been more of like a ‘work by myself’ person because I don’t really like relying on other people. But it definitely helps to realize that you know, that’s not always the case like you can definitely use people for support and especially with group projects. […] If we had an option to work by ourselves I would but now I won’t necessarily do that not just because of the split work but because you get a lot of different perspectives on different topics.”

Reed remembers doing a variety of activities within the ELP classroom like archeology, debates and mock trials. While these activities might not fit traditional curriculums, Reed acknowledges the way in which they prepared him for middle and high school.

“[ELP] definitely helped keep me focused because it was something that I was really challenged in. And it honestly helped me find things I was interested in, too,” Reed said. “Then afterward, I was going into seventh grade. I feel like it really helped me be prepared for it, like I was really worried about seventh grade because when my parents just talked it up a lot I felt like, and it was very easy and I think that part of that is definitely to ELP. A lot of things that we did in that class prepared me for that.”

Gabriel Conrad ’26 was involved in ELP at Horn Elementary and agrees that the program strengthened his ability to focus. “I think it helped me develop just like, you know, locking in skills, or I just got to focus on something for a bit. Definitely. Yeah, I think I use the skills that I learned in ELP today,” Conrad said.

When asked whether or not ELP affected his decision to take AP and honors classes and if he felt well prepared for them, Conrad replied, “Yeah, I mean, I feel like definitely the knowledge that like, ‘Oh, I’m a gifted kid so I can do advanced placement’ and, you know, gave me confidence to do that. A bit at least. And yeah, it helped.”

Aside from Reed’s experience with ELP and the social and academic benefits he received from the program, he has mixed feelings about the exclusive nature of the program.

Sophie Bergman ’27, who participated in ELP at Horn Elementary from grades fifth through sixth, also experienced mixed feelings about the exclusive nature of the program but in a different way. Bergman found herself reevaluating her mindset as a student after she continued on to Northwest Junior High and now West High.

“I think [ELP] did prepare me as a student but I also think it kind of didn’t help because, for a while, I always felt better than everybody else. Like, I was like, ‘Oh, I’m in the smart class. So I’m smarter than all of you’,” Bergman said. “ But now I realized that I was just smarter in certain things. Like I’m good at those IQ tests, but English and reading I’m not that great at. Like math I’m better at but some things I’m not as good at so it kind of made my self-esteem go up a bit too high.”

Through Bergman’s two years in the program, she remembers a business and number-heavy curriculum. Including building her own website and an online library and learning a variety of coding techniques.

“So during the program, what we [were doing] was not challenging. It was just different from what we were doing in class,” Bergman said. “[…] It was a lot of work to do like I had to do some things out of class, but it wasn’t challenging, just a lot of work,” Bergman said.

While Bergman didn’t feel that the program was super challenging, she still acknowledges that ELP prepared her for what was to come, similar to Reed and Conrad. She learned that she could succeed in AP and honors classes and learned useful skills.

“It taught me a lot about business, which I think is just helpful. Likewise, learning how to do a lot of coding was definitely somewhat helpful,” Bergman said. “I think [ELP] did help. It taught me a lot.”

Evolution

In recent times, defining standards of ELP have shifted. The program is entering a major movement- student inquiry. Students seek a topic of interest and let their curiosity take the reins. Through curiosity, students ask more questions, resulting in a deeper understanding of given concepts. This learning style is designed to better prepare students for the advanced track in middle school and high school.

“So making inference, you know, giving students background but having them hands-on, make inferences or do what people do in their career and figure things out, then they have all sorts of questions that may not be in my lesson plan that we then pursued because that’s what they’re interested in. So it often takes us in different directions takes us deeper and we all learn from it,” Chapnick said.

This movement is changing the way in which students navigate being gifted and talented, extending the benefits of ELP beyond elementary school.