In the middle of the country, deep in the heart of Iowa, hiding in between uniform acres of soybeans, cornfields and pig farms lies one of the greatest comeback stories of all time.

The rolling golden prairies that covered more than 85 percent of the state during its acceptance to the union in 1846, now represent less than one percent of the total land area. In recent years, however, the importance of prairies has come to light, and in southeastern Iowa, Iowa City schools are taking the lead on restoration and education. University of Iowa professors, high school teachers, and elementary classrooms have joined efforts to create a movement of community, resilience and sustainability.

Iowan farms lay at the heart of the meat industry in America, leading the country in corn and soybean production. Most of these crops are turned into feed for livestock, which then goes into markets for human consumption. A major reason why the Iowan soil is primed for agriculture is the impact of prairies. With roots reaching nearly 30 feet into the earth, and the plants providing the soil with key nutrients like nitrogen, areas that were once covered by prairie are now the most fertile soil in the United States. Iowa alone produces over 15 million dollars of corn every year, according to a report by Iowa State University.

Additionally, prairies are a crucial puzzle piece in the United States’ ecosystem. In prairies as small as 16 acres, over 300 different species of plants and animals can be found, making it one of the most biodiverse biomes in the world. The variety of plant types within prairies also provide a unique advantage in the fight against climate change, with the long stems and dense brush giving off a cooling effect.

Since the mid 1970s, Dr. Stephen Hendrix of the University of Iowa has been conducting research on the importance of pollinators like bees and butterflies in agriculture and prairies. Graduate students buzz in and out of his room, all leaving notes on a communal whiteboard. His university office reflects his lifelong commitment to his field of study, with cabinets filled with dozens of glass display boxes, in total containing around 20,000 bee specimens collected over the course of 50 years.

Hendrix himself acts like the bees he studies, with his infectious joy and the way he zips around the room, pulling out diagrams, specimens and studies. Hendrix has published many studies pertaining to pollinators in prairies, studying organisms as diverse as Californian almond trees to Iowan native Amorpha canescens, as well as a variety of pollinating bugs. Recently, he’s been focusing on what he calls “remnant prairies.”

“What the little remnant is, it’s like an oasis in a desert for these bees,” Hendrix said. Conducting studies with University of Iowa graduate students, they researched the remnant prairies and came up with surprising results. The diversity of bee species showed little change regardless of the size of the prairie. The change was in the number of bees in total. The largest factor impacting diversity of bees was the surrounding environment. “When it’s all agriculture, the diversity goes down,” Hendrix said.

The next question for Hendrix and his students was the effect on wild prairie pollinators for agriculture. Typically in mass-crop farming, one to three plant species will be grown, with the species changing each year in order to keep the soil healthy and fertile. In Iowa, the major crops are soybeans, corn and oats. What Hendrix and his students started noticing was the ever-present connection between plant diversity and bee diversity. Farms that contained prairie remnants also boasted higher diversity of bees. Additionally, farms that had higher diversity OF CROPS?? produced a wider variety of fruit sets, meaning more plants were showing the stage of becoming fertilized and flowering. By incorporating native plants and naturally diverse remnant prairies into farming and agriculture, produce output can be increased.

This application of using native plants to increase crop output is now being applied around the country. Hendrix traveled to California to study the effects of bees on almond trees, and found similar results. While the wild bees and the farmer-purchased bees rarely interacted, they also pollinated a wider variety of trees, leading to an increase in almond production. The interaction previously studied by Hendrix, where surrounding agriculture negatively affected the prairie diversity can also work inversely, in the case of the California almond groves. When the farms were surrounded by or interspersed with local plants, diversity of plants on the farms was able to increase.

Hendrix’s work has shown a new frontier in the world of agriculture. By working in tandem with the natural environment, both the native landscape and the output and profit of local and corporate farms can be increased. Additionally, it provides a less expensive alternative for locally-owned family farms to increase output. Iowa’s movements towards small systemic change in agriculture have given a new life to the American landscape and farms around the country.

Hendrix’s determination to study the remnants and fragments of prairies led to the creation of the Iowa Roadside Prairie Restoration Act, which has led to an increase in the planting of small prairies across Iowa, predominantly in metropolitan areas. Before the bill was passed in 2015, the grass in the middle of roads and highways was mowed each year. Much of his work on this act was in collaboration with Iowa City West High School teacher Brad Wymer. As a result of the research by Hendrix and Wymer, those grassy islands were sowed with native prairie plants and left to grow. This has led to hundreds of small remnant prairies, providing stronger biodiversity and countless more oases for pollinators.

One such remnant prairie grows outside of Iowa City West High School, where Wymer teaches. It has been providing an outdoor classroom for biology and environmental science students for nearly 50 years. Wymer has been a long-time pillar at West, finishing up his 30th year. Growing up in Lawler, Iowa, a small town of around 500 people, Wymer was raised outdoors, working in the creeks to catch crawfish or on farms. After attending the University of Northern Iowa, Wymer developed another interest in education. Wymer’s love for the outdoors translates to his classroom, with around 20 plants decorating the shelves, sparse between posters of native Iowa plants and diagrams of the human body. With a booming voice and a seemingly bottomless pool of energy, Wymer commands the classroom and is always looking for new ways to work with students. Since starting at West, he has taken charge of maintaining the prairie for 25 years.

“When I first started here, the prairie was really in ill repair. So [the] typical grasses had invaded and were pretty much running the show,” Wymer said. Determined to restore the prairie, he called in the Iowa Department of Natural Resources and a Johnson County biologist. In 1998, the prairie was control-burned, and replanted with seeds of native plants. Since then, West High students have used the prairie for a variety of lessons, such as measuring the goldenrod population in the grassland and mapping the prairies’ fight against invasive species.

“The prairie has always been the hook for us,” Wymer said. “Everyone’s got that uniform experience.” Each year, AP Environmental Science and teacher-selected biology students chart biodiversity and study the growth of the native goldenrod in the prairie. Goldenrod can be used to track the health of a prairie, when you compare its numbers to the number of an invasive species. In a chart detailing the goldenrod population from 2014-2023, the numbers show a steady increase in the number of goldenrod plants. Each year, students went out into the prairie, choosing five or six plants to study and compare to the native goldenrod. Since 2014, goldenrod populations have grown by around 50%.

Prairies provide a unique advantage in the fight against climate change, with deep roots up to three and half meters deep and knee-high grasses. Another popular AP Environmental Science lesson is how to study microclimates. Encouraged by Wymer, students measured humidity and temperature inside the prairie in comparison on the lawns directly next to it.

Prairies naturally provide a cooling effect, while traditional mowed lawns pale in comparison.

“There’s a really dramatic difference,” Wymer explained. “Then you start thinking about, okay, what are the implications for that if we have a lot more prairie versus a lot more lawns? Well, there’s going to be a natural cooling effect.”

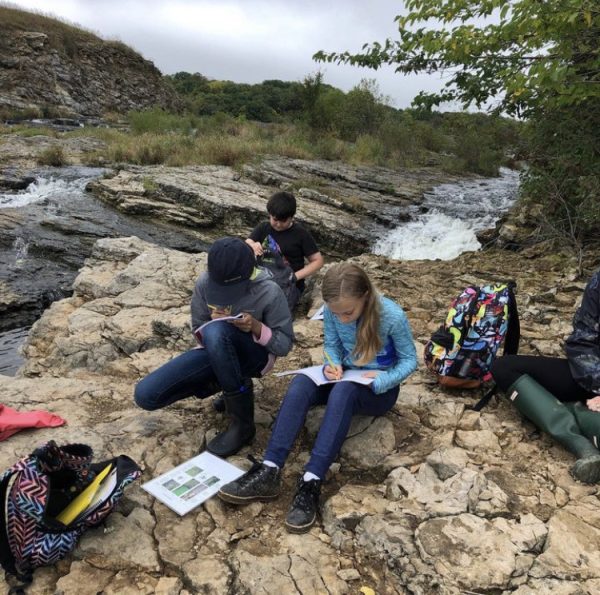

The opportunity to learn outdoors had a profound effect on the students. Students from both of Wymer’s classes, AP Environmental Science and biology, noticed a difference in their learning before and after their time in the prairie at the beginning of the year.

Wymer’s unusual teaching style has impacted students of all ages as well. “The way I run my class, there’s an exploration phase, and then I fill in the gaps,” said Wymer. This style of education allows students to find their passion and talents, and collaborate with others to fill in the spots they find weakness in. The prairie provides a new environment for students to form rapports within the class and increase their understanding of the natural world.

With his tried and true method, Wymer has inspired many students to form their own ecologically-based clubs, with the most recent being the Biology club, headed by Sadie Frisvold ’25.

“It’s so hard to get active in the community and the best way is through the school,” Frisvold said. Frisvold has found a home in the field of environmental science, with an inclination towards ecological conservation. She first recalls becoming passionate about conservation in seventh grade over quarantine. “I realized there were a lot of issues in the world, but it felt like climate change was one I could actually have an impact on,” Frisvold said. Her involvement in AP Environmental Science has inspired her to actively work to create change within West High. She now heads the Recycling Club and encourages students to engage in eco-friendly behavior.

She marked her yet another turning point being the prairie lesson. “I was much more interested in the class after we were able to go out into the prairie. It was easier to learn than just staring at a computer screen all day,” Frisvold said. The prairie as an extension of the classroom, instead of an accessory, has been the catalyst for many students’ plans for secondary education. Frisvold had always planned to major in chemical engineering, but after Wymer’s AP Environmental Science class, she is now planning to add in an environmental science specialty.

Lea Abou Alaiwa ’27 noted that Wymer’s biology class had a profound impact on her career paths for the future. “Going out into the prairie at the beginning of the year is when biology started to become really fun,” Abou Alaiwa said. “I started remembering what makes me really excited about science.” The prairie is a defining moment for many freshmen, highlighting a crucial difference between the science classrooms in junior high and highschool. Wymer’s hands-off approach allows students to develop their confidence in science and their own abilities.

One early formative experience for many Iowa City Community School District students is the School of the Wild program, held at Lake MacBride State Park. At School of the Wild, park rangers teach lessons to sixth grade students outdoors. Students do a variety of activities such as bird identification, fossil recovery and prairie exploration. Frisvold remarked that School of the Wild was one of her first opportunities to be able to learn hands on, and sparked her interest in biology. “It was a really cool experience, being more immersed in nature,” Frisvold said.

One of the schools that attends every year is Norman Borlaug Elementary School. Named after a famous agriculturalist, Borlaug Elementary takes special interest in cultivating students’ knowledge and understanding of the natural world around them. Sixth grade teacher Jill Shafer has led her students on the School of the Wild trips for eight years. She noted the importance of allowing a positive learning environment for students to explore interests in a unique way. “I think it’s important to get people out of their comfort zone. And this is an opportunity to do that in a safe, controlled way,” Shafer said.

Additionally, with the onset of hyper-urbanization and concrete jungles, the possibility of outdoors exploration is becoming a rare opportunity for young children. School of the Wild seeks to provide this experience for kids. The school seeks to build off of this formative experience, and much of the science curriculum for the rest of the year is built around expanding on the lessons taught in School of the Wild. “The kids are learning because then it becomes ‘I can see it. I can touch it. I can be in it.’ And I think that makes a big difference,” Shafer said. By implementing a unique learning experience for students, the Iowa City Community School District is inspiring students to take control of their own education and become active in the community.

School of the Wild focuses on educating young students about the ecological history of Iowa, and has a lesson focused entirely on the past of the prairie and the impact of its disappearance. Each year, students enter the prairie to play “predator vs. prey” and study the native plants and animals that no longer inhabit Iowa, such as the bison. The prairie provides another space for students to connect with their history, and can create many fond memories. “When I think of the prairie, it reminds me of happiness,” said sixth grade student Bella Boudreau. “Because it’s, like, light and colorful.”

Her classmate, Willa Jones, had a different perspective. “It’s complicated, because the more I learn about this stuff, sometimes it’s sad.” Jones mentioned that learning about how animals and plants are going extinct can be overwhelming, but School of the Wild also made her happy to be in a place that was fully nature.

The entirety of Shafer’s class shared the same opinion of the importance of the prairie. Prairies provide a home for hundreds of species of plants, insects and animals, and is one of the most biodiverse ecosystem types. In a small fragment prairie such as the one by West, there are an estimated hundred different plant species alone. “It would’ve been really bad if a complete habitat would’ve just gone out,” said sixth grade student Reyansh Suhakar. “There are lots of animal species who could have gone extinct thanks to that.”

Within Iowa City, there are generational efforts to preserve the landscape that was nearly eradicated not so long ago. The dedication of researchers like Hendrix, educators like Wymer, and leaders like Shafer and the ranger of Lake MacBride is single-handedly creating the next generation of scientists and conservationists.

In the last 20 years, Iowa City has worked tirelessly to restore the lost prairie habitat, encouraging families to plant pollinator gardens and funding programs like School of the Wild and local wildlife camps. Without the prairie, the agricultural, economic and educational landscapes would be unrecognizable. These multigenerational leaders are shaping the future through nothing more than some common grasses.

“These little small remnants are really, really important things,” Hendrix said.

Design by Josie Schwartz