Off-color

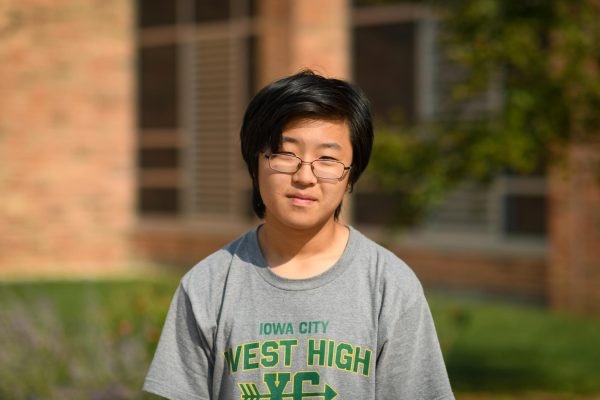

Erin Moses always wondered what it would be like to be colorblind. Now, she knows.

November 23, 2016

“It’s very cool, but it sucks.”

Those are the words Erin Moses ’20 uses to describe being colorblind. Colorblindness is uncommon but not unheard of, and is more common in men than in women. But Moses is a special case; she wasn’t born that way.

“I grew up with this colorblind best friend and he was red-green colorblind,” she said, chuckling a little. “And I had wondered at some points what it would be like to be colorblind, but I always just shrugged it off and said, ‘No, I’ll never know.’ And now that I do know, it’s not so great.”

Acquiring colorblindness–color deficiency as it’s called clinically–is a symptom associated with some eye diseases and side effects of some drugs, including diabetes medication and tuberculosis treatment. However, Moses’s condition stems from a rare side effect of fluoxetine.

Her case is even more rare considering that acquired color deficiencies are “typically more in the blues and yellows as opposed to the reds and greens,” according to Mark Wilkinson, a professor of clinical ophthalmology at the University of Iowa.

“When we first started noticing that something was going on with my vision, we were going to get wine for my aunt for Christmas. And we had this bag and my parents and my sister… were saying, ‘This bag is red,’ and I’m like, ‘It’s pink, what’s happening, are you guys colorblind or something, what’s happening here?’” She laughed a little bit, and then added, “And it was apparently very, very red. That kind of just triggered everything.”

Soon after, Moses’s parents took her to an ophthalmologist and she was given a color blindness test.

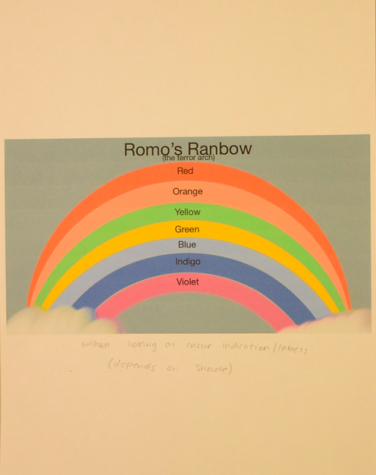

“We went to the doctor and I didn’t pass the colorblind test,” she said. “And that’s the weird thing, because they were like, ‘Are you red-green,’ and it’s weird because I can kind of tell where things are on the color wheel. I know if I look at something and I think it’s red, it’s probably orange or pink.”

Knowing where things are on the color wheel may seem a negligible skill, but it allows Moses to keep pursuing art, something she’s been involved in since junior high school.

“When I developed the colorblindness, I kind of stopped going [to art club],” she explains. “And then I went back for eighth grade, because I did realize I had this past knowledge, and not a lot of colorblind people have that past knowledge, so I should take advantage of it. I went back and I would read colored pencils, but eventually it got annoying and I stuck to just pencil drawing, just in gray.”

Moses’s unique brand of being color deficient, however, means she doesn’t have to stick to gray if she doesn’t want to.

“I have past knowledge of what things look like,” she clarified. “I know that leaves are green. I know grass is green. But sometimes when I look at it, it frustrates me, because I know I’m wrong, and that’s kind of the difficult part. It’s kind of helpful when people write on colored pencils the color of it, because if I pick up a green pencil and it says ‘green,’ I will color leaves that color.”

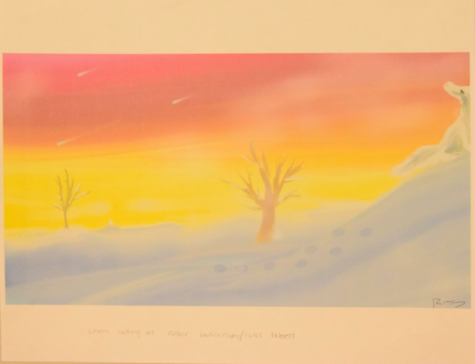

Although she can, Moses doesn’t usually delve into the world of color when she does art. However, that didn’t stop one of her teachers from running an experiment.

“I had a science teacher that thought it might be interesting to see what I would create if I didn’t ask anyone what the colors of the pencils I was using were, or if I didn’t read the labels on them,” she said. “I did that for her, and apparently it was really interesting. It might kind of be my art style, I guess, even if I don’t know it.”

But while art is creative, most classes in school don’t work the same way.

“I remember in Spanish class, there was this weird point in time where we were learning colors, and I knew most of the colors,” she said. “But they would hold up these slates with a color on them. And they’d say, ‘Alright, say this color in Spanish.’ And if it was red, I would know that that’s ‘rojo’ but it didn’t look red, so I’d say something else. It kind of came across that I didn’t know the material. But if the word was up there, in English, I could’ve translated it.”

Moses stopped taking the medication that caused her condition, and she’s starting to recognize colors better than she did before.

“Some colors I’m kind of noticing are getting a little better for me,” she said. “I can’t tell if I’m getting better at guessing or if it’s improving, but it might be possible that the colorblindness could go away in the future.”

It’s very possible that Moses’s vision could be getting better.

“In some cases the color vision can come back, by… stopping the medication causing the reduced color discrimination problem,” Wilkinson said.

Just in case, though, Moses has already thought about what might be a challenge for her.

“Driving might be an issue. I have to pay attention to the position of the lights instead of the colors,” Moses said. “I get green and yellow mixed up, which is pretty bad. It’s possible, probably harder, but it’s possible.”

However, Moses isn’t letting her color deficiency deter her from living her life.

“It’s opened a couple of people’s eyes,” she said. “You don’t have to have normal eyesight or anything to be an artist. People can’t tell you what you can’t do.”