During his campaign, President Donald Trump ran on a platform of protectionist economic policies alongside strict immigration reform. These policies aim to restrict international trade and protect American businesses from foreign competition. After winning the election, Trump followed through on both agendas by taxing countries’ imports via tariffs.

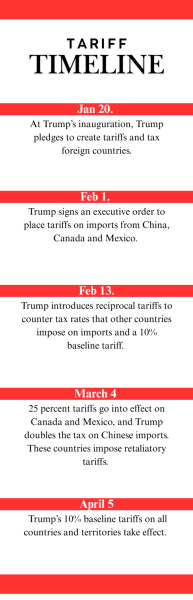

“We are establishing the External Revenue Service to collect all tariffs, duties and revenues. It will be massive amounts of money pouring into our Treasury, coming from foreign sources,” Trump said during his inaugural address Jan. 20. Less than two weeks later, Trump signed an executive order to impose his first set of tariffs Feb. 4, which included a 10% tax on Chinese imports and a 25% tax on imports from Mexico and Canada.

A tariff is a tax that a country can put on its imports, usually to protect its domestic economy. However, tariffs don’t just promote a protectionist economy — they are used as a negotiation tactic, hence Trump’s vision of using tariffs to control immigration rates.

The White House stated in a Fact Sheet that the tariffs on Mexico, Canada and China are the result of Trump holding the countries accountable to their promises “to halt illegal immigration and stop poisonous fentanyl and other drugs from flowing into our country.”

Anne Villamil, an economics professor at the University of Iowa Tippie College of Business, criticizes the hastiness of the Trump administration. Villamil believes that the administration skipped the critical step of negotiating.

“Tariffs are used after negotiations have failed to solve trade problems,” Villamil said. “This episode is very unusual [as] unfortunately, the tariffs have resulted in a trade war, which is a very serious problem. Typically, after negotiations have failed, [tariffs] are a way to give your trading partners an incentive to adhere to international trade agreements.”

The White House released a formula that was used to calculate rates for the reciprocal tariffs. While it looks confusing, economists have simplified the formula to the trade deficit divided by total imports. Due to its simplicity, economists are questioning the accuracy of this formula in calculating the complexity of tariffs. This may also be the first instance in U.S. history where a blanket formula was explicitly used to calculate a tariff. Villamil is certain that the numbers being put into the formula are too high, inflating the rates.

“One of the people who devised that formula, who’s at Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago, says that it has been applied inappropriately, that the numbers the administration used are incorrect,” Villamil said. “The researchers who have come up with the model have said that the numbers are about four times too high. They got the magnitudes wrong.”

After a series of tariffs targeting steel, aluminum, auto imports and European alcohol, Trump announced a generalized 10% tariff for every country that exports to the U.S. that went into effect April 5. Alongside the baseline tax came an extra rate for countries such as China, Japan, South Korea and the entirety of the European Union.

However, many countries have since responded with retaliatory tariffs. China retaliated with taxes on a variety of American-made products. The EU vowed a tariff on American goods worth $28 billion. Canada announced their tariffs on $100 billion worth of American products, with Mexico threatening similar action.

Retaliation like this is a well-known sign of a trade war, where two countries use taxes in an attempt to harm the other country’s economy. Villamil finds that trade wars often fail to properly address offenses.

“There are legitimate bilateral disputes. The most effective way to resolve some of those disputes [would be to] say, ‘If you do not do whatever the legitimate grievances are, then we will act in unison to restrict your access to markets.’ It is surprising [to not] expect other countries to retaliate,” Villamil said. “Trade wars are destructive for all parties. We are reducing global gross domestic product.”

Economic conflict often points to global turmoil as disputes over markets can quickly translate to larger, harsher hostilities. World history teacher Lia Ritter emphasizes the role of economic conflict in the past.

“Economics is just money to some people, but it can lead to hard feelings, which can tumble into something worse,” Ritter said. “…[It] was post-World War II when world leaders thought of the solution [where] if we have economic codependence with each other and come up with institutions where we can solve our problems, we won’t have another global conflict.”

Besides global reprimand, Trump cited improving domestic economies as another reason behind his tariffs. Many economists are left to wonder how domestic manufacturers are supposed to keep up with the rapidly decreasing access to foreign products. While increasing domestic production is seen as a net positive, Villamil notes the differences in implementing manufacturing policy from past presidential administrations, specifically citing a lack of planning.

“Setting up new firms in the U.S. will take two to three years, typically. Under the Biden administration, there was something known as the CHIPS Act, and it was a specific plan to produce more [semiconductor] chips in the U.S. for strategic reasons, in partnership with Taiwan. We’ve seen no such plan in the U.S. under the current administration,” Villamil said.

The uncertainty that follows Trump’s tariffs is a driving factor of economic decline. After several pauses and adjustments, the tariffs are proving to be turbulent to American consumers.

“The policy seems to be changing on a daily basis, and that is extremely disruptive. Consumers cannot plan in an environment where there is this much policy uncertainty,” Villamil said.

The U.S. stock market experienced some of this turmoil in early April, with major stocks like Microsoft, Meta Platforms, Amazon.com, Apple, NVIDIA, Alphabet and Tesla all entering bear markets, where the stocks declined more than 20% from their peaks.

However, the market has since soared as American and Chinese officials held trade talks in early May. The two countries have agreed to a 90-day pause on their tariff war with China vowing to reel in some of their retaliatory tariffs as the U.S. cuts their import tariff from 145% to 30%.

Ritter explains how this would be a win for both countries as trade tends to benefit both entities.

“It has been a mutually beneficial relationship, rather than everybody else just taking from the U.S. We can’t be a leader in [the] world stage if we start to cut ourselves off,” Ritter said. “Other countries aren’t going to want to take that sitting down. And we’ve seen that currently with retaliatory tariffs, but also what [world leaders are] saying out loud.”

World leaders, including French President Emmanuel Macron, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez and more have condemned Trump’s tariffs. Former German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, voiced his concerns in a speech given April 3.

“The recent tariffs decision by the U.S. president is fundamentally wrong and is an attack on a trade system that has created prosperity all around the world, itself an American achievement,” Scholz said.

Ritter agrees that the trade system has been a key component of globalization and modernization for thousands of years.

“Trade is the reason that people started communicating and forging paths with each other early on in history,” Ritter said. “We think back to the development of the Silk Roads, where we had routes being created throughout Eurasia, among communities who are trading with each other. Trade is [also] the exchange of religious ideas, cultural ideas, [and] being exposed to different people, technologies and innovations. Those kinds of things have been exchanged for hundreds of years throughout the context of [trade].”

Barriers to trade, such as tariffs, can be detrimental to economic growth and even international relations.

“Tariffs are a way to signal to another country, ‘Hey, we’re kind of doing our own thing,’” Ritter said. “[Tariffs] put an ‘us against them’ mentality where there is one winner and one loser, whereas in a globalized view of trade, there could be many winners in this global economy.”

Villamil agrees that such an offensive strategy will not be successful in solving bilateral issues. Instead, she urges a return to one of the primary ways tariffs were first used: as a negotiation tool.

“We should get around a negotiating table and solve these bilateral trading problems,” Villamil said. “That’s where we should have started, at the negotiation phase, not the penalty phase.”