Coming full circle

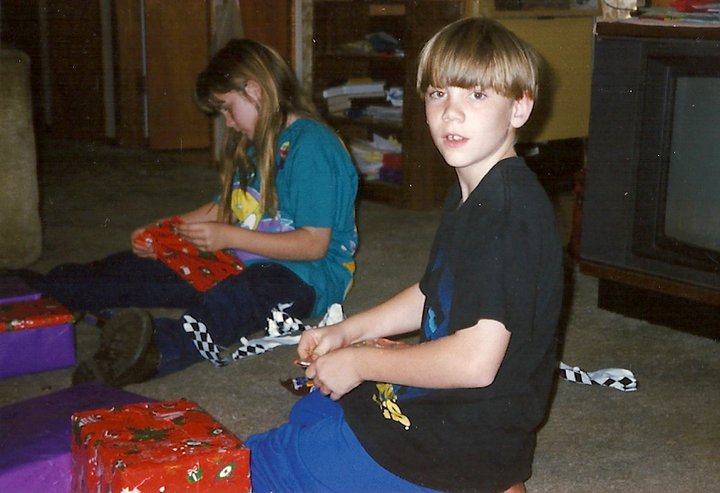

Jeff Conner first roamed the West High hallways as a fourteen year old, and has since returned to teach and be the support system he so appreciated from his time at West.

April 16, 2017

Although Jeff Conner failed Mrs. Wikner’s chemistry class, that didn’t deter him from coming back years later to teach that same subject just down the hall.

For Conner, teaching just seemed right. He would get the opportunity to do science every day, but also support students who may need it most—a support that helped him make it through his time at West High.

Conner grew up the youngest of five children, and in a home where his parents were very “hands-off,” Conner learned to raise himself. His parents divorced when he was young, making his life “pretty unorganized.” His dad was an alcoholic, and his mother’s side of the family has a history of drug addiction. Thus, he didn’t have a conventional support system at home.

“[My] parents were like, ‘[Let’s] make sure he’s got food, and he’s got water, and he sleeps in our house,’” Conner said. “I thought they loved me as parents, but were not really invested in my life.”

Although Conner had four other siblings, he didn’t confide in them. His siblings were extroverts who did drugs and occasionally got in trouble with the law. Conner was an introvert, in part because he felt embarrassed of his siblings’ rambunctious behavior.

Along with feeling secluded and different at home, Conner was battling with mental illness. Although he wasn’t clinically diagnosed at the time, he recalls specific childhood memories that point to his anxiety.

He remembers the look on his first-grade teacher’s face when she saw the bald spot he created on his head from pulling out his hair. Or the time when he broke down crying to his grandmother when he told her he couldn’t do his paper route—but didn’t know the reason why.

According to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America, 18% of adults in America battle anxiety. Conner chooses to share his mental health story with his science classes every year with the hope that they will understand they’re not alone.

From his time as a student at West High, Conner recalls certain teachers who inspired him. Tas Anthony, a former social studies teacher, is one of them.

“I remember Jeff,” Anthony said chuckling. “He began to really start thinking about and discovering himself. As a teacher, you love that.”

Conner scored a 1 out of 5 on the AP test, but that didn’t deter Anthony from getting the opportunity to know his student.

“I really admired him and kids who had a persistence to learn,” Anthony said. “It really was sincere encouragement [I gave him]. The role as a teacher is to get [the student] to do their best.”

Conner recalls this encouragement vividly and cites Anthony as one of his models in teaching.

“Every day I showed up and he showed that he cared for me,” Conner said. “And I was terrible at AP European History.”

Conner empathizes with his students and hopes to be the teacher they can count on to understand that life isn’t always smooth sailing.

“When I was 14, I did not have it together. Whenever I’m having a really stressful day with my students, I try to think, ‘What was I like when I was 14?’”

During his sophomore year of high school, Conner found a girl that would he would become codependent and emotionally attached to. She filled the void that Conner was lacking from his family and showed a general interest in his well-being. She proved to be a pseudo-psychologist, in whom he would confide and instill his trust in about everything.

“I thought she was the only person who cared for me,” he said. “I decided I needed to lose weight and work on [my] physical appearance… [I] stopped eating food as a result of that. I lost around 60 pounds over the course of six months.”

Conner would eat either an apple or an orange in the morning, and that would sometimes be it for up to two days.

“Ever since then, I’ve had a really weird relationship with food,” he said.

He has since found ways to cope with his eating disorder after its peak in high school. However, he is aware of the relapses that can occur.

“I’m in pretty good place. It’s rare for me to get the feeling that I shouldn’t eat,” he said.

Conner and his girlfriend were rarely apart, and this emotional attachment proved to be detrimental.

“When we broke up, I had a major identity crisis. I didn’t want to go back to being a kid,” Conner said. “I was pretty lost for a long time.”

Conner graduated a few months later and went on to study chemical engineering—a suggestion that had been made by his ex-girlfriend’s mother.

“I hated it,” he said. “I saw no meaning in what I was going into as a career, other than making a lot of money.”

Instead of finding validation through cashing in the biggest paycheck, Conner found validation in numbers, whether it was watching the scale number go down as he ate less and less or watching his GPA remain high in college.

“To prove myself, I decided in college I was going to get a 4.0,” Conner said. “My identity became very wrapped up in academic performance.”

He graduated from the University of Iowa with a Bachelor’s degree in science education, and went on to receive his teaching license.

Teaching allowed him to spend each day doing science, but also strive for making an impact on a student who may need it more than ever.

“Any excuse I can get to talk about something, not physics or chemistry, I try to. It’s about meaningful connections I can make with students,” he said. “A goal I have is for all of my students to feel like I’m personally invested in them and that I care about them.”

Maureen Head is one of Conner’s fellow science teachers. She’s also someone Conner says he can have “stupid fun” with.

“Stupid fun would be like when we’re here at six o’clock on a Friday night and we decide that we need to set up a lab,” Head said. “We’re awkwardly trying to do it and everything becomes funny.”

Head has witnessed Conner from his first day of teaching to present day.

“I was like ‘oh my gosh this guy is awkward, how is he going to become a teacher?’ But now I know we share some of the same awkwardness,” she said. “I truly admire him. [He focuses] on a nurturing classroom and nurturing the kids as individuals.”

April Allen • Mar 30, 2018 at 7:57 pm

Can Connor please get in contact with me. By email, or phone. My phone number is 5252309352.