Hate is a virus

With a rise in anti-Asian violence sweeping the nation, many reflect on its impacts and deep-rooted history in the U.S.

In response to a rise in anti-Asian racism, several Stop Asian Hate rallies have been held across the U.S. this year.

Despite a clear sky and shining sun, a somber cloud hung over the Pentacrest lawn. Speakers stood on the steps of the Old Capitol behind eight buckets of flowers — one for each life lost.

“Everybody was crying,” said Ijin Shim ’24.

In the wake of the March 17 spa shootings in Atlanta that killed eight people, six of whom were Asian American women, around 250 people gathered in downtown Iowa City for a vigil. For many, this attack represented the culmination of over a year’s worth of heightened anti-Asian racism resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Though the shooter claimed his motives were not racially charged, many activists, including Rebecca Wu, believe otherwise. Wu is a junior at Alhambra High School in Alhambra, California, and interns for Stop AAPI Hate, an advocacy group and reporting database created in response to the rise in anti-Asian sentiment.

“After reading the quote from [the Cherokee County Sheriff Captain] about how … [the shooter] did this because he was ‘having a bad day,’ I thought that was an understatement because I definitely think it was a racially motivated hate crime,” Wu said.

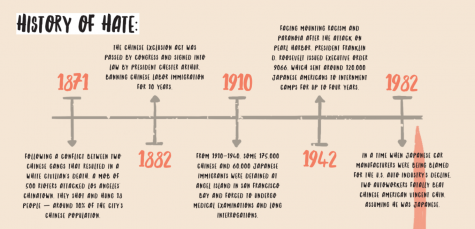

In addition to a “bad day,” authorities said the suspect attributed his shootings to a “sexual addiction.” However, some argue that given the historical fetishization of Asian women, the spa attacks cannot be disconnected from race. Tracing back to the Page Act of 1875 that banned Chinese women from the U.S. by labeling them “prostitutes,” stereotyping and objectification of Asian women has remained a trend in this country for over a century.

“When people think of Asian women, they’ll just think … we don’t have a voice, that when we experience this kind of assault, we’ll just stay quiet,” Shim said.

Though racial violence has been exacerbated for Asian women over the past year, it hasn’t been limited to one gender. Stop AAPI Hate received over 3,795 reports of anti-Asian discrimination from March 19, 2020 to Feb. 28, 2021. Of these reports, verbal harassment and avoidance were the most common, at 68.1% and 20.5%, respectively. Most publicized, however, has been the third-largest category: physical violence, which made up 11.1% of incidents.

An 84-year-old Thai man was killed after being shoved to the ground during his morning walk in San Francisco Jan. 28 of this year. A Filipino-American was slashed across the face in a New York City subway Feb. 3. Also in New York City, a 65-year-old Asian American woman was knocked to the ground and repeatedly kicked. In response to such incidents, students have experienced emotions ranging from disappointment to disbelief.

“My first thought was, ‘No way, that can’t actually be happening, right?’” said Catherine Yang ’23. “After that initial shock faded, I was like, ‘Wait a minute, that’s so messed up.’”

According to Stop AAPI Hate, about 7% of last year’s racist incidents against Asian Americans targeted people over 60 years old. Viral videos of seniors being shoved, robbed and assaulted have made Shim, among many others with elderly Asian relatives living in the U.S., anxious.

“I’m scared … [my grandparents] don’t speak fluent English, and I guess people don’t like that. [People] tend not to be kind to them,” Shim said. “You don’t know what will happen.”

Shim, however, says this fear isn’t new.

“They have received hate and racism for so long … now they don’t even get mad; they’re just so used to it,” Shim said.

Despite a long history of anti-Asian racism, the recent surge of both physical attacks and xenophobic rhetoric has been linked to the pandemic. According to Pew Research Center, almost a third of Asian Americans have reported being subject to racist slurs or jokes since the pandemic’s outbreak.

As the first cases of COVID-19 surfaced, some students recall hearing such remarks from peers. Looking back on comments she overheard, from racist slurs to bat-related quips, Wu feels disappointed.

“For the people who were using these terms and knew that it was insulting but they were still just doing it … I viewed it as pretty ignorant and very immature,” Wu said.

Yang was relatively unphased early on, but after seeing the damaging effects of these comments, her viewpoint shifted.

“It wasn’t really a background thing; it just masqueraded as that,” Yang said.

Wu feels the rise in anti-Asian sentiment was also reflected in former President Trump’s speeches and tweets, in which he often labeled COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus” or “Kung flu,” sparking anger from activists and Chinese officials alike.

“I saw it as a lot of immaturity, ignorance and bullying,” Wu said. “A lot of people told [Trump] to stop; he knew the hate crimes were going on [and] he knew the consequences of his actions, but he still continued.”

Yang believes that although Trump incited acts of violence, these attacks were inevitable.

“[Trump] definitely helped trigger more hate, but I think people who believed him … probably would have found a way to hate Asians. They would have found any excuse to do it,” Yang said. “Trump just happened to be the trigger because he was in a position of power.”

In response to instances of xenophobia, President Biden signed a memorandum Jan. 26 condemning anti-Asian hate. He announced further actions his administration would take on March 30, including hate crime reporting measures and the re-establishment of the White House Initiative on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, which has an added mandate to promote Asian “inclusion, belonging, and opportunity.”

This mandate addresses a sense of exclusion that some Asian Americans face as a result of the “perpetual foreigner” stereotype, one that puts them in a constant position of the “other” in Western society.

“If I say, ‘I’m from Iowa,’ they’ll ask me, ‘Where are you actually from?” Shim said. “They don’t consider us as Americans.”

According to Yahoo News, 64% of Asian Americans reported being asked similar questions under the assumption that they weren’t from the U.S.

“Being a minority group or expressing their culture doesn’t always mean that they are foreign,” said Nik Sung ’22.

Sung is a founding member of Dongari, West High’s Korean Culture Club. Throughout April, the club has been selling shirts to fundraise for Asian Americans Advancing Justice, a non-profit that supports the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community.

Along with donating and raising awareness, Sung believes having open discussions in educational spaces would be helpful in supporting the AAPI community.

“Schools, from elementary to high schools, should make students feel comfortable to talk about these issues of hate,” Sung said.

Wu also believes education is crucial for progress.

“I hope that people take the time to inform themselves … about current events to foster insightful conversations with their peers,” Wu said. “Really use this time as a learning and reflecting opportunity.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

(she/her) Maya is a senior and this is her third year on staff. She is the feature editor for print and is super excited for another great year. She loves...

(she/her) Grace Huang is a senior at West High. She is a second-year designer and artist for print, but this is her first year on staff as the Health &...