Money moves

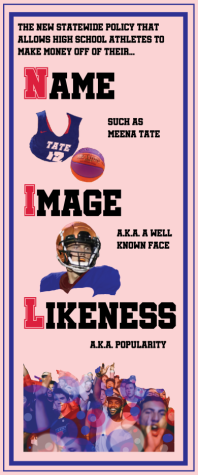

The new statewide policy titled Name, Image and Likeness, or NIL, is changing how student-athletes can benefit financially through Iowa high school sport participation.

West High athletes, Meena Tate ’23 and Jack Wallace ’25, share their perspectives on NIL.

A person’s name, appearance and personality are all qualities that others remember them by. But in this competitive day and age, it is unlikely an individual will make money based solely on those attributes. That was until NIL came along. Now, businesses and brands are providing student-athletes opportunities for cash flow while they are still in school.

The Iowa High School Athletic Association, or IHSAA, and the Iowa High School Girls Athletic Union, or IGHSAU, released a new policy Aug. 17, referred to as NIL, that permits high school athletes to accept money for their name, image and/or likeness. This means that high school athletes can be paid to appear in a specific company’s commercials and wear their brand. They are also prohibited from affiliating with any competitor brands. The payments for NIL deals vary greatly depending on factors, including the sport, the individual and the business.

“Some people get $25 for doing a Cameo,” Eddie Etsey ’98, West High alum and the current University of Iowa Associate Athletic Director for Technology and Data Analytics and one of the sports administrators on the Senior Leadership Team, said. “Some people do commercials for $100, or some people get free pizza. It all depends; there really isn’t a set amount.”

Companies make these deals because they believe that the athlete will bring in profits for them. Athletes are many people’s role models, so if an athlete is sporting a specific pair of shoes, a fan may want to emulate them by buying the same pair of shoes.

NIL at the high school level is based off of the collegiate level’s NIL policy, which was put into effect by the National Collegiate Athletic Association, the NCAA, in June 2021. This was a major change in college sports because, since the founding of the NCAA in 1906, NIL had been outlawed, meaning that college athletes couldn’t have partnerships with businesses, but professional athletes could. However, college athletes rarely make it to that big stage. In fact, less than 2 percent of NCAA student-athletes eventually become professional athletes according to the NCAA.

Jack Wallace ’25, the quarterback for West’s varsity football team, recognizes that in order for an athlete to receive financial benefits from a sport, they need to put themself out there.

“Now you have to get your name out, and you have to advocate for yourself,” Wallace said.

With the ability to get an NIL deal earlier in an athletic career, strict guidelines have been constructed. High school athletes must follow the rules put in place by their state. Therefore, high school athletes in Iowa who are involved in NIL activities must follow the rules and regulations produced by the IHSAA and the IGHSAU.

Iowa high school NIL regulations can be complicated. For example, high school athletes are not allowed to sport their school’s mascot, name or logo while participating in NIL activities, such as an advertisement for the brand.

Furthermore, an NIL deal isn’t solely based on the athletic abilities or accomplishments of a high school athlete. Talent aside, student-athletes often receive NIL deals based on how their face and name will look in an ad. Wallace summarizes the basis of this NIL rule.

“It’s more about you rather than your athletic performance,” Wallace said.

Although no one at West has received an NIL deal as of print time, student athletes have mixed feelings about the fairness of NIL deals.

Meena Tate ’23, a West varsity girls’ basketball player and Dartmouth College commit, views NIL as being unfair, but is also able to see the positive opportunities it will bring to some athletes at the high school level.

“I feel like [NIL deals] should be based on your athletic ability and not just how popular you are, but good for you if you’re making money from your sport as a high school student,” Tate said.

Wallace follows NIL updates closely, especially for athletes at the University of Iowa and has noticed a difference in NIL participation based off of social media presence.

“Social media following has a huge impact on people’s names,” Wallace said. “Iowa football players who don’t get playing time are getting money because of their big following on social media and because people like to see them.”

Etsey has seen both the upside and downside of NIL deals for student-athletes going to the University of Iowa. Distinct from the beliefs of University of Iowa Athletics, Etsey believes NIL deals could harm students’ educations.

“NIL takes away from students focusing on getting an education versus focusing on ‘how do I make quick money?’ Now, granted, there are some situations that families from low income housing and from different groups would really benefit from the NIL money,” Etsey said. “But, the way it’s presented now is it takes away from your college experience … Now you have to worry about the business side of being a student-athlete.”

Wallace has a similar take on how NIL could affect a high school student-athlete’s education and choices, especially during the recruiting process.

“I feel like the new NIL law could take away from academics,” Wallace said. “At the college level, recruits are going to bigger colleges mainly for the money and not for academics because they want that fame.”

The NCAA maintains that colleges cannot use NIL as a way to influence recruits to commit to their athletic program, but, according to Etsey, there are potential loopholes. For example, a business can make it known to a particular college that they are willing to offer an NIL deal to a specific recruit. Then, a college recruiter can pass that information on to that athlete. As long as the college isn’t directly offering money to a recruit to come to their school, NIL deals can be used as an incentive in the recruitment process without any punishment from the NCAA.

“You’re not supposed to use NIL as a recruiting tool for incoming high school students, but people do use it,” Etsey said. “Personally, I don’t think that’s right, because instead of selling a program and what they want to get out of the program, you are now enticing them with resources, which is going to make their decision somewhat easier.”

Tate is one student-athlete who still considered the quality of the academics above all else during her D1 recruitment process for women’s basketball.

“An NIL deal wouldn’t affect where I would go to college, but in the sense of other people who had different motives, I think it definitely would affect their decision-making,” Tate said.

In considering the future of this new law, Etsey hopes it will support equity among sports of varying popularity.

“NIL is meant for everybody, but just as a society, we put value on certain sports and not on all sports,” Etsey said. “In a perfect world, I think we need to put value on all sports to be fair and equitable.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

(she/her) Ella De Young is a senior at West. This is her second year on staff working for West Side Story as the print managing editor. When she's not...

(she/her) Lily Prochaska is a senior and this is her second year on staff. She is the print sports editor this year. She plays volleyball and loves to...

(she/her) This is Athena's third year on the WSS print staff, and as a senior, their last year. She is entertainment editor, and enjoys all things satire,...