The Arab World is a region comprising of 22 countries in Western Asia and Northern Africa. Arabs, while united by culture and history, consist of a diverse group of people from countries ranging from Sudan to Lebanon to Iran. Fundamental practices are based on the religion of Islam, as an estimated 93% of Arabs are Muslim; the religion’s influences are showcased in architectural practices based on geometrical shapes to region-wide celebrations of the Mawlid, Prophet Muhammed’s (SAW) approximate birthday. However, other religions are prevalent as well, including Christianity and Judaism.

Culture

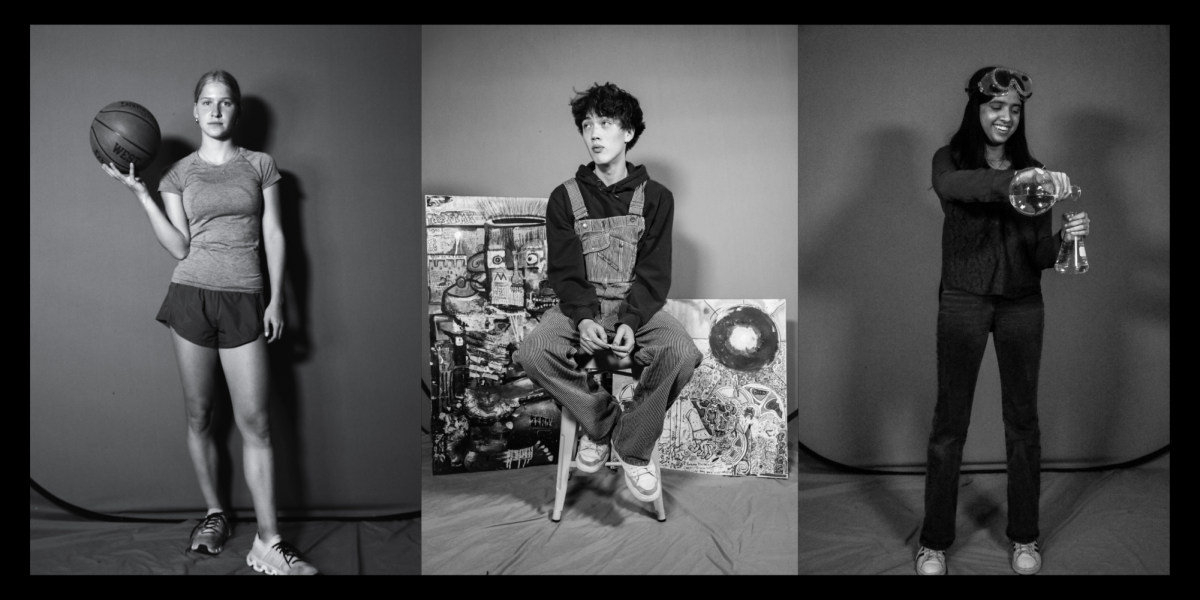

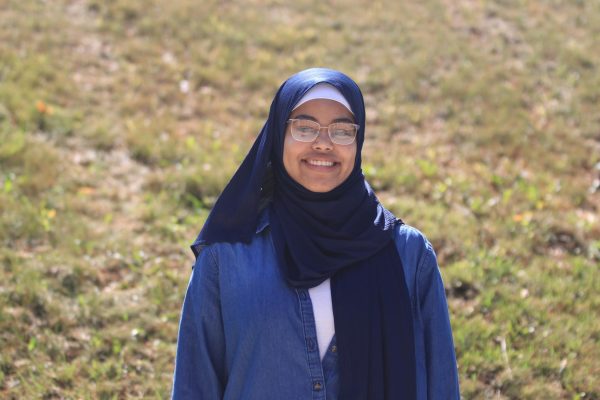

Despite living in America, Arab culture remains a large part of the everyday lives of many Arab Americans. For Palestinian-American Jinann Abudagga ’25, her culture is most prevalent at home.

“Arab culture has always been a big part of my life. I go home, I practice Arab culture, my house is decorated with Arab decorations, we eat Arab food all the time, my name is Arab. It’s always part of me and my daily life,” Abudagga said.

Though she acknowledges many sectors of Arab culture are well-established in her daily life, Abudagga emphasizes food as an important aspect.

“Like any other culture, food is a big part of [Arab] culture, especially for Palestinians,” Abudagga said. “[Everyone attends] the lunches we have with my family on Fridays, and we eat traditional food. It’s a big tradition in Palestine, so food brings us together.”

In addition to Arab dishes, Abudagga identifies other aspects of her culture that make up her identity, such as the Arabic language.

“My family tries to speak Arabic on Fridays. I’m not allowed to speak English at home on Fridays to keep my Arabic good,” Abudagga said. “We go to the mosque on Fridays, and I feel like that’s a big part of Muslim culture, but not necessarily all Palestinians are Muslim. We get together with our Arab community and celebrate, eat our food, talk to each other in Arabic.”

Family-oriented weddings are also a prominent part of many Arab cultures. Arab countries like Sudan celebrate a marriage with religious ceremonies, a unification celebration and a henna gathering, which consists of close friends and family coming together to decorate the bride’s — and, in some countries, the groom’s — hands with henna, a natural dye. However, while similarities occur in the process, Palestinian-American Shahd Suleiman ’26 notes that each country still holds its own unique traditions.

“Most weddings in Arab countries are very big and extravagant. You invite many people, and there are multiple parties that go into place. They can go on at the mosque, and then the engagement party will be done somewhere else,” Suleiman said. “The night before a Palestinian woman gets married, we have henna, which happens in a lot of Desi and Islamic cultures. Palestinian women [also] have their mother or someone close to them [bring] a tatreez dress and [give] it to them the night before their wedding.”

Many Arab weddings invite music, dancing and traditional customs. Sudan, a country with an African and Arab-blended culture, incorporates a sword dance to specific celebrations. The sword dance consists of using decorative swords as chorographical props accompanied by traditional drumming and dancing. Sudanese-American Ahmed Elsheikh ’24 describes the vibrant energy of his own parents’ wedding.

“We were able to watch [my parents’ wedding video], and there were all these beautiful drums playing the entire time, and then I saw the parallels that remind me of the drumline here at school,” Elsheikh said. “There was also sword dancing, and it’s just a beautiful thing.”

Although Sudan is generally viewed as an Arab country due to its Muslim-majority population, Elsheikh notices a unique culmination of African traditions as well.

“Sudanese culture has much more African influence [than other Arab countries] — it kind of blends together, and in this way, is really unique,” Elsheikh said. “A lot of Sudanese music has a very specific Sudanese [sound] to [it]. When I hear Arab music, it’s close to my heart, but there’s lots of little things, like the use of flutes and violins, that are very unique to Sudanese music.”

Living in the United States, Elsheikh has maintained his religious identity and a strong connection to his roots.

“Islam dictates a lot of our culture. Religion is very important to me, especially these past couple of years when I’ve been kind of trying to find myself,” Elsheikh said. “I find sticking to my roots really important because I know that’s where all my family’s from.”

Community

One of the most notable aspects of Arab culture is the family-like community, which is a significant aspect in the lives of many Arab people.

“I really like how Arab culture is very family-centric,” Abudagga said. “I’m really close with all my cousins. They’re some of my best friends, and I really appreciate that about [Arab culture].”

Abudagga has noticed that the family-like community is a large part of her life, not only in Palestine but also in Iowa City.

“I have family friends [in Iowa City] that I’ve known since I was born, and they’ve been extremely supportive. We’re all Arab, and we treat each other like family no matter how long we haven’t spoken to each other,” Abudagga said.

Elsheikh finds this same sense of family within the Sudanese and Arab communities. During Eid Al-Fitr and Eid Al-Adha, two important Islamic holidays, Muslims within the region come together for community prayer, socializing and general celebratory practices. Elsheikh notes that a diverse array of individuals, Arabs and non-Arabs, come together for these two special occasions.

“Even though most of the people [in Iowa City] that are Arab are Sudanese, on Eid, you still see [Arab Muslims] and non-Arab Muslims all coming together for prayer and then going out to eat,” Elsheikh said. “I feel like there’s more of a family presence.”

Having a community of Palestinian friends allows Abudagga to hold onto her culture. Her Palestinian friends have been a pillar for her to lean on, especially in times of hardship.

“It really helps to know that there are other people like me, and I’m not in this alone. For example, my friend Rana is also from Palestine. When the war broke out, me and her really got to connect over how we felt,” Abudagga said. “It’s a great way not to lose our culture. We’ll do Palestinian dances together. Whenever we go back to Palestine or the Middle East, we’ll bring stuff for each other.”

Elsheikh emphasizes that Sudanese individuals value community gatherings and generally socialize for long periods of time.

“[Sudanese people] talk a lot. It’s a very well-known thing. Let’s say you’re at a family friend’s house, and you’re hanging with the younger kids, and your parents are like, ‘Alright, we’re going to leave now.’ Then you’re standing there for another hour, and they’re like, ‘No, no, we’re gonna leave,’ but they just keep talking and talking,” Elsheikh said. “That’s a thing for Arab people, but I think it’s even more for Sudanese people.”

Suleiman finds that no matter where you come from, in any Arab group, people always stick together and hold a strong bond through their culture.

“Everyone’s very welcoming in Arab culture in general. Most people are very welcoming and open and charitable and they all have a very deep connection,” Suleiman said. “Even if you guys just met each other for the first time, everyone’s very open with each other. I felt like they have a sweetness to them.”

Identity

While similar in community activities, Elsheikh points out that North African Arab countries differ from Middle Eastern countries in regard to physical features and appearance.

“A lot of differences are geographical. Over time, people adapt to their surroundings,” Elsheikh said. “[Some] Sudanese people have darker skin than other Arabs from the more Asian part of the Middle East.”

Elsheikh has also noticed that Sudan’s location puts many Sudanese individuals in a unique and often disconnected position.

“Being Sudanese is an awkward space where you’re stranded in identity. [Sudanese people] are not exactly Arab, but we’re also not exactly African,” Elsheikh said. “I feel a little different from people who could, for example, be Saudi Arabian, Palestinian or Yemenis.”

Abudagga finds a similar situation within the United States, where she notes that people’s misconceptions about Arabs negatively impact her daily life.

“One of the biggest stereotypes is that all Arabs are terrorists [or] all Arabs support terrorism, which is not the case. I definitely have experienced some things where people treat me differently because of where I’m from or the way I look or because my mom wears the hijab,” Abudagga said. “A big part of Arab culture is to love everyone and treat everyone equally, so terrorism is the exact opposite of what Arab culture does.”

Abudagga emphasizes that she also faces racial prejudice because of the stereotypes tied to her Arab name.

“[I see stereotypes] especially at airports … They look at my name, and I get pulled aside for security,” Abudagga said. “I’ve been put in an interrogation room before, and I feel like that definitely is because of my name.”

Suleiman has also noticed that Western individuals have preconceived notions about Arab people.

“I feel like they see us as angry a lot of the time. In daily life, no one is like that,” Suleiman said. “Of course, there are reasons to be angry, [like] politics. We’ll be upset, but Arabs themselves are not angry or mean people. They’re very respectful and calm.”

Abudagga points out that as a young person traveling alone via airplane, these stereotypes can have an even greater negative effect.

“It was definitely frustrating because I am a child traveling alone without my parents. I’m scared and want this to go as fast as possible,” Abudagga said. “I made it through security just fine — I obviously don’t have anything on me. It’s not fair that I’m getting pulled aside because of the way that I look or the way I sound.”

Elsheikh acknowledges that he has experienced similar stereotypes and believes such misconceptions reinforce a cycle of hatred.

“People think a lot of us are lazy. A lot of them are more rowdy people in the halls, and there’s the whole conversation to be had of, ‘Does that make them a bad person?’” Elsheikh said. “Some of it is a cyclical thing. A lot of [Arab people] are already living not the easiest and you don’t want to just judge them.”

Stereotypes about Arab individuals transcend their identity, focusing on garments worn specifically by women. Suleiman emphasizes that some in the Western world view modesty as a form of oppression, even if such modesty is the choice of the wearer.

“Americans will say that to reclaim feminism, people will dress however they want and do whatever they want. But when it comes to dressing modestly, that’s going backwards,” Suleiman said. “In reality, [Arab women] are just reclaiming [feminism] in the same way as someone going out with less clothes. If you’re dressing in more [clothes], I don’t understand why that’s an issue for people [because] it’s really just reclaiming [feminism in a different way].”

Because stereotypes overgeneralize the Arab population, Elsheikh feels that people often confuse different identities with one another.

“I wish people were able to differentiate a little more. There are people who don’t know the difference between Muslim, Arab or Arabian. I wish people were a little more knowledgeable about it,” Elsheikh said.

Despite the prejudices against Arab culture that remain, Abudagga believes that as society moves forward, education will ultimately help dispel these assumptions.

“[Arab culture is] a beautiful culture,” Abudagga said. “I wish people would take the time to learn about our culture instead of taking what the media says about our culture and automatically going with that.”