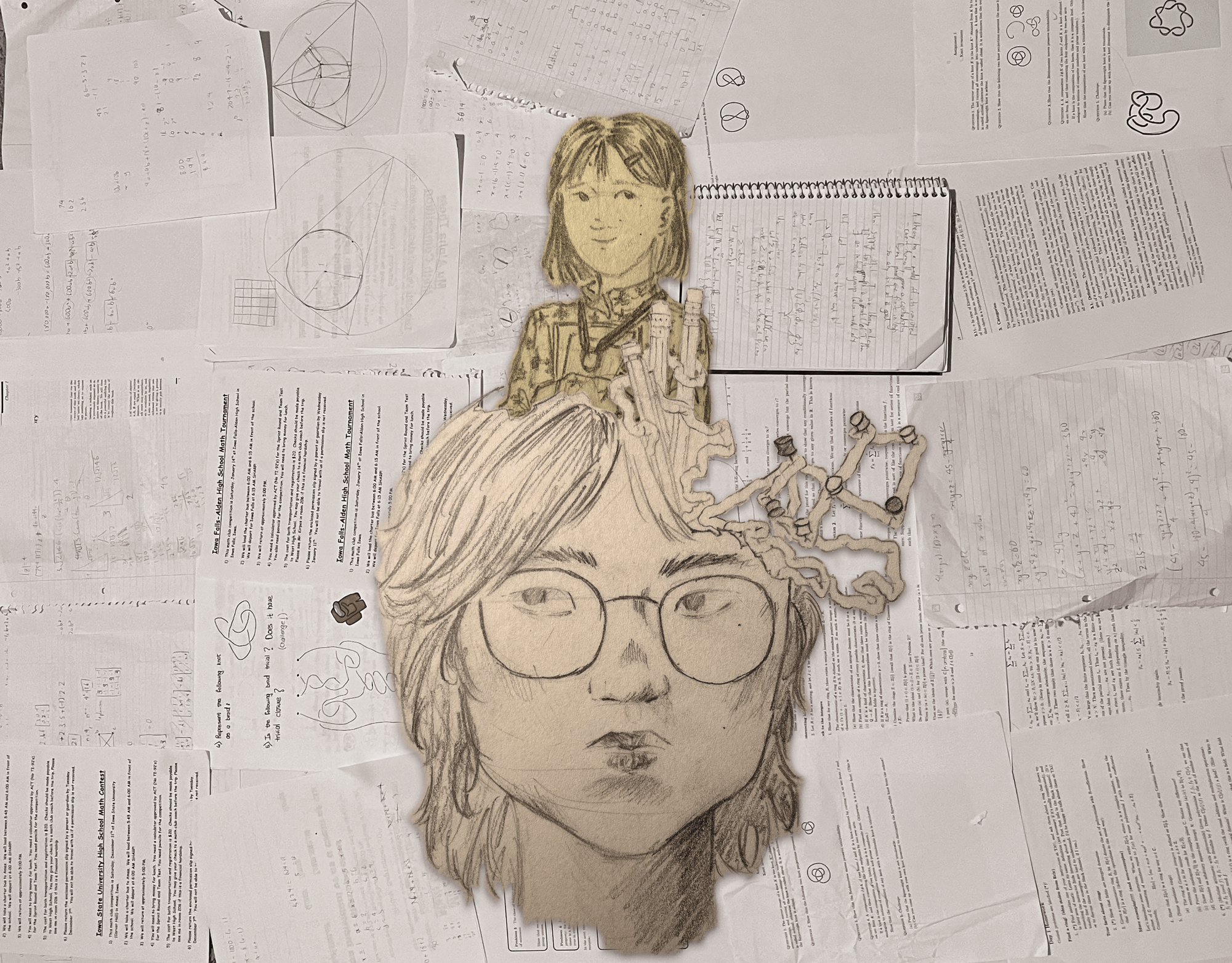

It’s over. All the olympiads that took over my life and controlled my self-worth, all those endless hours hunched over a textbook and grinding practice problem sets — it’s over. I can confidently say that in terms of olympiads, I failed miserably.

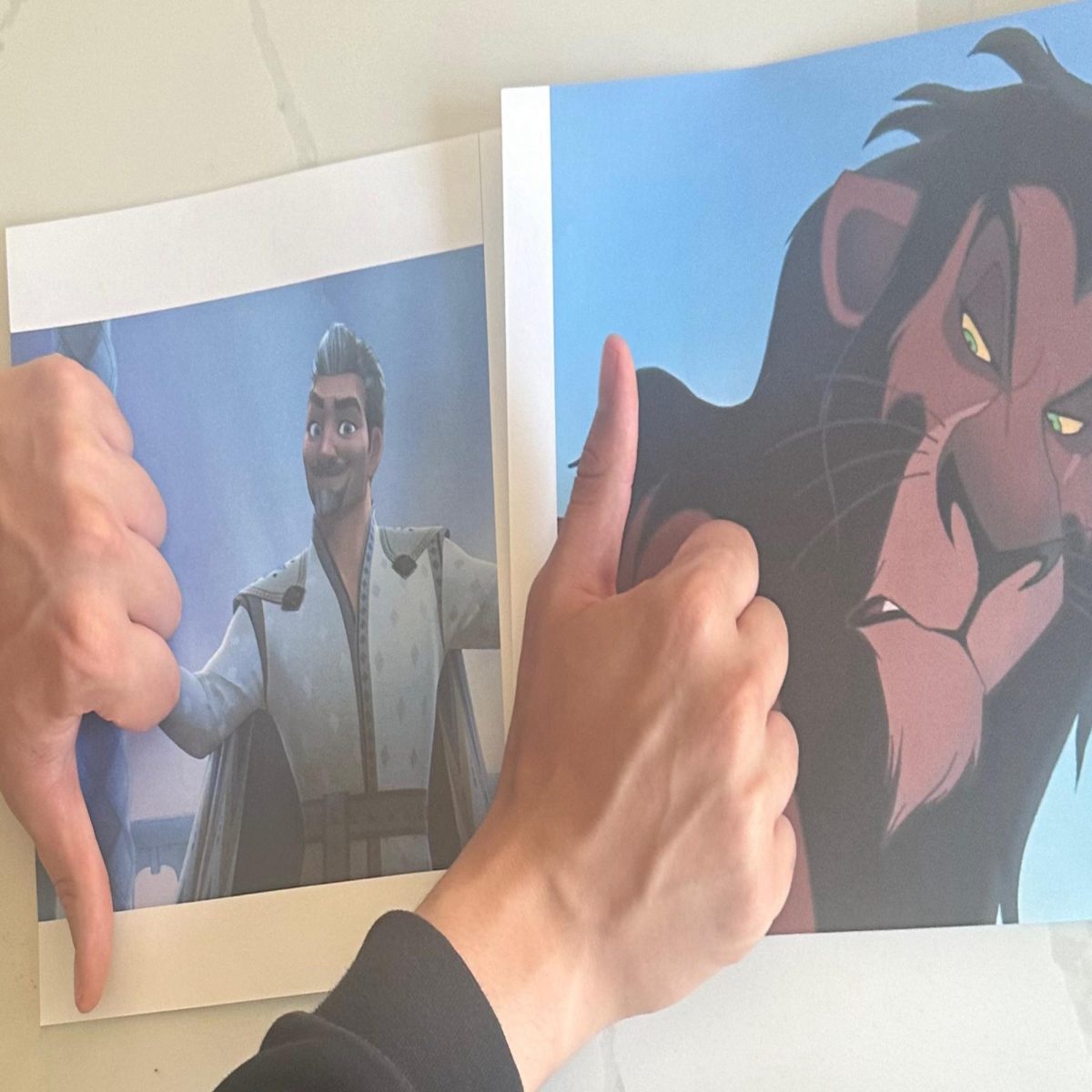

First, for the mercifully uninitiated, olympiads are knowledge tests. Think trivia bowl, but much more focused on problem-solving in a singular topic. Math olympiads, which I primarily competed in, are the most famous, but there are also olympiads in chemistry, astronomy and even linguistics. They usually consist of several rounds of selection tests that eventually qualify the top students for the coveted prize: a seat on Team USA to compete at that subject’s international olympiad.

How far did I get?

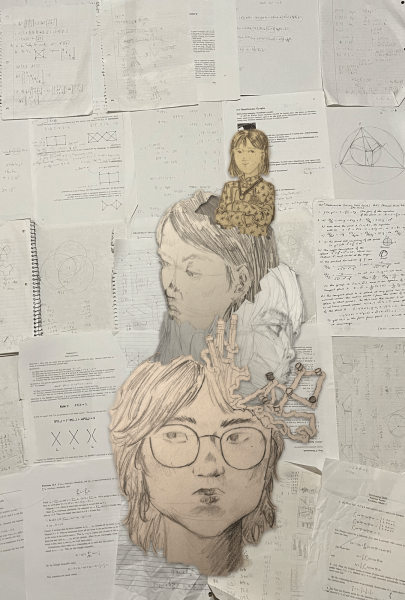

Fresh out of junior high with a perfect score on the AMC 8, I thought I could get as far as I wanted. Numbers played together beautifully because I’d put in the hours of work, reading textbooks and solving practice sets; I could juggle fractions with ease and calculate angles at a glance. I loved math and worked for it, and it rewarded me amply.

I went into the summer and the pandemic with even more fervor to improve over my next four years of high school, which I thought was equivalent to all the time in the world.

Instead, I quit. Well, quiet-quit.

As a freshman, I threw myself into studying. I worked through textbooks, took practice tests, tabulated theorems and mistakes — I did everything I used to. But when competition season rolled around, I scored significantly worse.

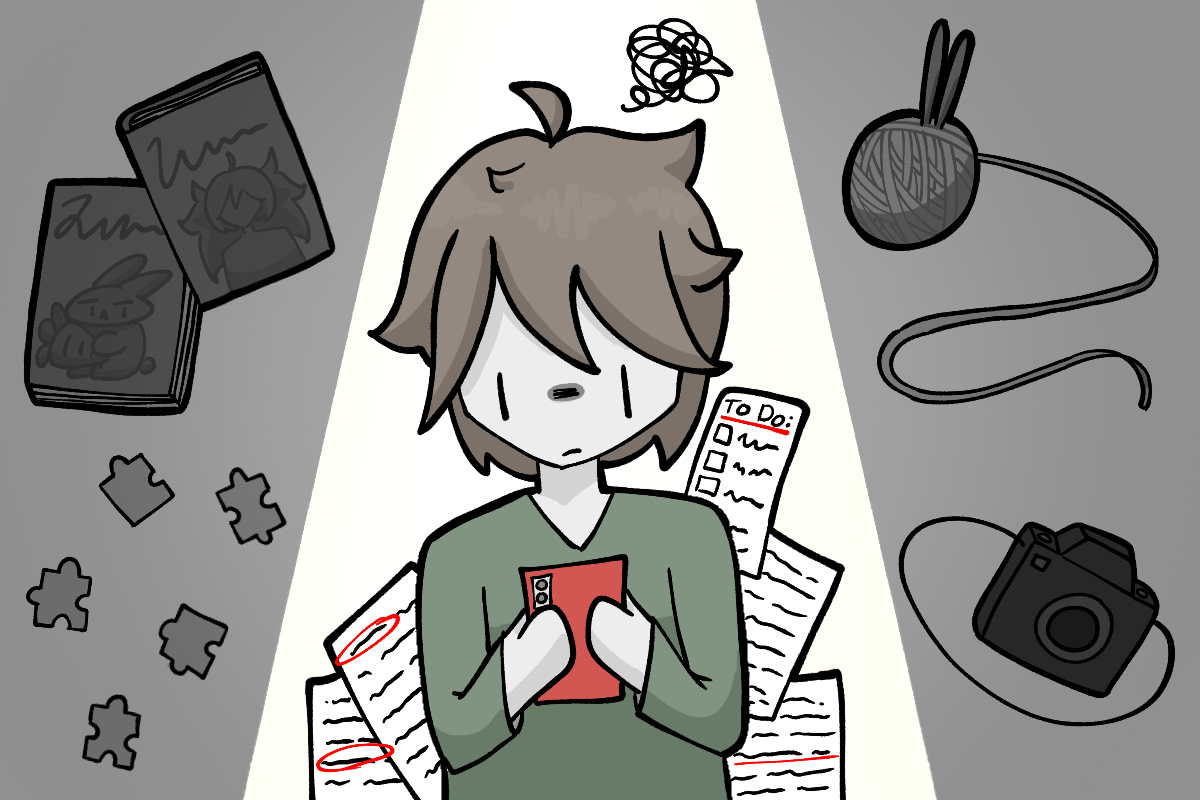

While struggling to learn the increased difficulty of high school competition material, I hated myself for my flagging interest, looking at the faltering scores that should’ve instead lit a fire under me. I couldn’t do anything right — Fermat’s little theorem made no intuitive sense; whatever hell De Moivre’s crawled out of wasn’t one that I could comprehend. I couldn’t even stay focused long enough to get past definitions. Whatever I did, the scores stayed unerringly, infuriatingly, constant.

I quit. I stopped seriously practicing, closed the textbooks and left them gathering dust. I’d failed; I wasn’t cut-out for math competitions. I was some, possibly improper, subset of lazy, stupid and weak-willed.

Some dim memory of the joy I’d felt, innocently poking at elementary permutations back in middle school, led me to begin tutoring competition math, locally and online, for the rest of my high school years. The irony of someone who’d given up on mathematics convincing pre-teens of the “joy of mathematics” was not lost on me.

I’m a senior now. This year was my last shot at competitions, and I thought, why not give the thing that’s sucked dry years of my time and self-confidence one last hurrah? Without any expectations, I dusted off my textbooks and gave myself two weeks to mess around before the competition. I was rusty, but somehow, with the pressure valve missing, I found a semblance of the old rhythm I had with numbers. Not quite a proper dance or juggle, but the muscle memory and the same joy I had when I first learned about permutations was still there, long-buried.

And now I’m left with the bittersweet wonderings of where I might’ve gone had I not quit so soon, had I allowed myself a break for the burnout. More than if I simply could’ve exponentiated my scores, but found more happiness with my numbers.

I do love math, and olympiads offered me opportunities to learn niche trigonometry and weird Euclidean cevian theorems they don’t teach in high school and never bother to in college.

And therein lies the triteness of my message: do things for their joy, learn things because they’re interesting. Don’t shoot for some integer cutoff; more often than not, statistics and a normal distribution will dash your hopes on the proverbial rocks of the bottom quartile. Shoot for the moon, if you fail, you’ll at least land among the stars, knowing lots more about parabolic trajectories. Q.E.D.