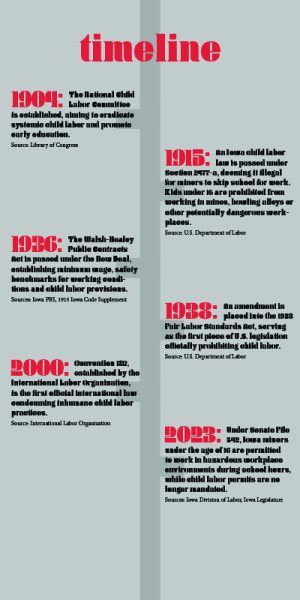

From the establishment of the National Child Labor Committee in 1904 to the International Labor Organization in 2000, the United States has undergone substantial change as a part of a greater international movement to restrict child labor. However, Iowa legislators revised Senate File 542 — which mandates safety standards for teenage workers — by implementing the Youth Employment Law. As a result, Iowa child labor laws were loosened July 1, 2023.

Under this new legislature, 14 and 15-year-olds can now work longer hours, and 16-year-olds can take on more commitments such as serving alcohol. Although SF-542 received general approval, with a 29-18 Senate vote, it actively infringes upon the conditions of specific federal laws. Despite this, alterations to Iowa child labor legislation were ultimately issued amidst a growing nationwide movement to repeal state protections for child laborers.

The benefits

For Trueman Arnold ’24, working as a minor was an opportunity to earn money while honing his interests in trade work. Arnold was first thrown into labor-based jobs at eight years old, immersing himself in projects such as diesel tech and roofing. Now, he works various large-scale jobs for farmers, ranging from welding to operating equipment. These jobs enable him to save money and gain work experience, with the goal of attending a welding trade school after high school.

“I’m a jack of all trades. I do a lot of trade work: farming, roofing, mechanics, welding, fabrication, framing, plumbing,” Arnold said. “I [will] probably go to a trade school down in Wyoming, called Western Welding, to be completely certified for pipeline work. I want to be one of the people who weld live gas lines that are on fire or underwater.”

Although Arnold finds personal fulfillment in his trade work, the working conditions are often dangerous. He admits that the hazardous environments make these jobs unsafe for teenage workers.

“When welding, I’ve been on fire a couple of times. If you ever see a hoodie that I wear [and] you look on the right sleeve, it’s burnt,” Arnold said. “About every single one of [my jobs have physical risks]. It’s hard on your body and terrible for you, but you might get money out of it. When I hit 40, I’m probably going to be seized up, barely moving.”

In contrast, Tessa Pitcher ’25 previously worked at an ice cream shop over the summer. While her job wasn’t dangerous, she echoes Arnold’s point that working conditions for younger teenagers weren’t ideal.

“[My previous workplace] wasn’t firmly planted on the ground, so a lot of times, it would shake [and] didn’t feel solid,” Pitcher said. “The [floor] of the building was a lot dirtier than you’d expect. I had dedicated shoes [for my job] because you could hear the sound of ice cream [under your shoes] — it was a really disgusting sound.”

Despite this, Pitcher believes that her summer job was worthwhile both for having an income and the skills it taught her.

“A job is super valuable, especially for young high schoolers. For me, it helps with calmness, shyness and patience, but also a lot of high schoolers aren’t in the position where their parents are going to pay for college, and starting to save up for college is a really important idea to have entering high school. Because college gets expensive fast, a lot of [guardians] won’t have money to put their kid through college, and the burden is on the child to do that, so I think [a job] is valuable no matter if you’re rich or poor,” Pitcher said.

The risks

While working as a teenager has its benefits, there are also many concerns. A study from the University of Washington found that students who worked more than 20 hours a week had, on average, worse grades than their peers who worked less. Diane Rohlman, the Director of the Healthier Workforce Center of the Midwest, has done research on how working can affect students.

“If we’re thinking about high school students and even college students, you’re required to go to class from eight to three, so work has to occur either before that time or after that time, and depending on how many hours you’re working, there are some restrictions on that,” Rohlman said. “Usually [sleep is] what [gets] sacrificed, and if you’re doing sports or you’re active in other civic things like the scouts, a band or show choir, all of that takes a lot of time too, and you still have to do your homework.”

This is part of why jobs are often regulated depending on the age of the worker. However, these regulations don’t always apply. Given that Pitcher worked at a small, local business, working practices weren’t often enforced. As a result, Pitcher and her teenage coworkers often performed uncommon tasks whenever their boss wanted them to.

“Weird stuff would happen because there was no one to keep [my boss] in check — no real higher-ups. The only comfort you had were the managers, or the people one step below her, which are high schoolers,” Pitcher said. “There wasn’t really a system for [my boss] to be balanced out. She would yell at you and do whatever she wanted to you in a way that wasn’t checked.”

Pitcher occasionally did other parts of running a small business, including going off-premises to pick things up.

“[Workers would do] a job for [the boss] that involved going off site, so we would have to get in the car with [the boss, their dog] and usually another co-worker. We all went up to [their] farm,” Pitcher said.

Rohlman also acknowledges the long-term effects that working within regulations at a younger age can have on development.

“When you’re born, your brain is developing, but that also continues when you hit puberty and doesn’t really stop until [the age of] 25, and [even then] people keep growing and getting stronger. Working long hours, because it can be risky, can lead to injuries and long-term disabilities. [But] it also has a lot of benefits; it gives you a sense of purpose and teaches responsibility [in addition to] putting money in your pocket. Some youth work because their families need their income in order to survive [while] other youth work for their own expenses,” Rohlman said.

Rohlman goes into more detail about how younger workers can risk their physical or mental health by overworking themselves if work isn’t regulated.

“Sleep is probably the biggest factor, and if you’re doing a physically demanding job, you could be very fatigued, which then increases your risk [when] driving,” Rohlman said.

These risks are often compounded by teenage workers putting themselves in more danger. Teenagers are less experienced and less likely to know how to handle new situations, which puts them at risk of injury.

“All workers can be at risk, but because of [teens’] inexperience and their reluctance to say, ‘Should I be doing this?’ or ‘Am I doing this right?’, [their risk is] increased. We know young workers are more likely to get injured on the job than older workers, but we also know this [is true of] new workers, and it doesn’t really matter what age you are. If you didn’t really work until you were 25, you’re still at risk just because of that inexperience,” Rohlman said.

This danger is often more prominent in agricultural fields, where labor laws are often not applied. Rohlman has seen how family farms take advantage of these loopholes.

“If you’re working on your family’s farm, there are [almost] no restrictions on what you can do or how long you can work. Most of our farms here in the United States are family farms. If you work for an agricultural employer, like your neighbor or runway farms, which makes those baby carrots and other [small crops], then there are some restrictions, but they’re less protective than if you’re working in any other industry,” Rohlman said. “Agriculture is one industry that has fewer regulations. Because of it, we know that more young workers are injured or even die on the job than they do in other industries.”

This lack of regulation allows teenagers to work in farming and run machinery that wouldn’t normally be approved for. Arnold has worked during harvests and ripped fields using large machinery because of the exclusions around agriculture.

“[During] harvest time, I was running [a] grain truck, grain cart and the harvester at the same time; I was working the fields,” Arnold said. “[I work for] four months because I rip the field four or five times, and we’re jumping from field to field to field.”

The future

Despite some of these risks, Iowa is one of many states that has lifted restrictions on child labor laws. These laws allow students to gain skills by joining the workforce. However, it puts these teenagers in danger. Rolhman believes such policies emerged due to a recent job shortage across the country.

“Employers are having trouble hiring enough workers. What some states are doing to address this is making the youth labor laws less restrictive. They’re letting youth work longer hours during school time, and in some cases, in jobs that were considered dangerous,” Rohlman said.

Still, for some, this work opens the door to more work experience, even if it’s just over the summer. Pitcher still thinks that working a job during high school is valuable, even if it’s not exclusively for the money.

“It’s important because we’re at an age [where] everyone is so socially awkward that it’s good to be forced to interact with people. If you’re not doing a bunch of extracurriculars, or you’re not feeling super stressed, it’s better to be productive with your time, gain skills and get experience, than going into the job market with no experience at all,” Pitcher said. “For a really long time, I was pretty socially awkward. Doing something where you had to directly interact with people, [and also] be nice and patient, has helped a lot with understanding that other people are just [like you]. You have to work together for everyone to get what they want.”

Even dangerous work can serve as an opportunity to gain experience in high-paying trades. For Arnold, this means getting a well-paying job and the ability to travel.

“There’s so [few] people in the trades. If I become a pipeliner or weld pipe for a living, I can travel all over the United States. I could probably go up to Canada [or] Alaska,” Arnold said. “I had a rough childhood, and I’m trying to escape it and get out as much as I can.”

Rolhman also thinks that entering the workforce is important, although she stresses the need for workplace safety.

“It’s important that everybody learns how to enter the workforce; most people will work at some point in their life. My only concern is to make sure they know how to protect themselves and create a place where people can work and gain the benefits, but also not be at risk for injury,” Rolhman said.