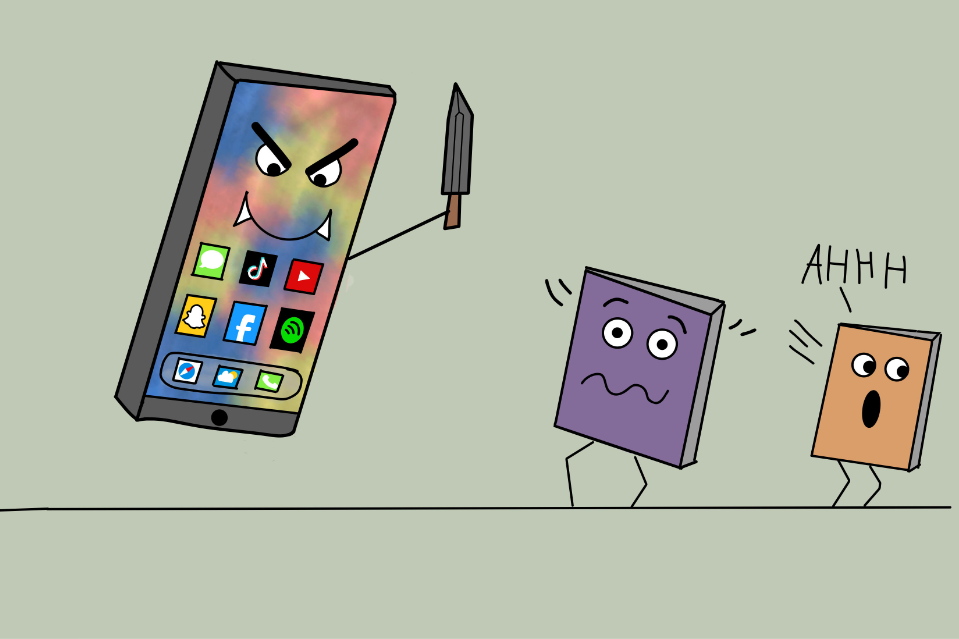

Walking through the West Library, it’s more common to see students scrolling through their phones than flipping through books. The West Library reports that in the 2023-24 school year, students checked out 800 less books than they did the year before and 2150 books fewer than in the 2021-22 school year. This trend exists outside the walls of West as well; according to a poll from 2022, the average American read 12.6 books that year, a drop from 15.6 in 2016.

Luke Reimer ’27 has noticed similar trends in the past three years as a volunteer at the Coralville Public Library.

“We don’t get a lot of high school kids [coming to the library]. We get a lot of junior high kids,” Reimer said. “I have some friends who [are in the] banned book club, and I went up to them at the club fair, and they [said that] no one likes reading anymore.”

Rudy dela Rosa is an AP English Literature and Composition teacher with the highest AP scores in America. After 24 years of instructing students, he was asked by the AP College Board to help revamp the program in 2016. He describes his work as “teach[ing] the AP College Board how to teach others.’” When asked about the significance of reading, dela Rosa emphasized different aspects of the skill.

“[Reading] gives us a chance to explore different avenues. [It] allows us to see different perspectives. It’s important for kids to be able to experience that, because it makes us more empathetic, more human and [more] relatable,” dela Rosa said.

The importance of reading not only lies in mastering comprehension and grammar; several educators, including dela Rosa, believe a student’s reading habits directly affect their writing ability.

“Here’s the thing: writers are readers. Readers are writers. Every book you’ve ever gone to pick up, that writer was a reader,” dela Rosa said.

John Cooper, West English teacher and instructor of Secondary Reading at the University of Iowa, has noticed correlating trends among students’ reading habits and their writing abilities.

“If you don’t read critically, the information you read might present clearly false claim[s] that are not founded in good research, which can then put an individual in the position of not being able to decipher meaning, because they don’t actually have all the information,” Cooper said.

Dela Rosa agrees and notices a similar relationship between student success and AP exam scores.

“[With] AP test responses, the kids who normally score the fours and the fives use works that are more complex and more nuanced,” dela Rosa said. “For example, Harry Potter or Hunger Games. They’re both very fun. They’re both very enjoyable. They’re good reads. The problem is, there’s really no meat on the bones. Everything is handed to you because those novels are written for a younger age. You really can’t write about [the] subtlety and nuance of a character or plot progression when everything is given to you.”

Given the prevalence of this concern, dela Rosa explains how to best avoid this issue.

“The students who get something with more meat on it, something more complex, something that is more subtle in the way it presents, they’re going to score higher because it allows them to explore concepts and characters that an easier work won’t allow them to do,” dela Rosa said.

However, in order to develop more advanced writing skills, Cooper emphasizes reading nonfiction and fiction in conjunction.

“Stories guide our understanding of who we are as people. Narrative is how we explain our history. Narrative is how we remember what works and doesn’t work,” Cooper said. “On the flip side, you have informational reading, which is supposed to be taught most often in history courses. But [frequently, history teachers are] so busy going in depth on [the] history [that] critical reading falls back on the shoulders of an English teacher.”

With reading affecting more than one aspect of students’ lives, educators are on a mission to curb any downward trends in reading skills. Cooper views the solution through a lens of socio- economics.

“We need to create a literary environment for [students] in their home. [My] research when I was an undergrad [found that] the best indicator of a high ACT score for a kid is how many books are in their home. We can’t suggest causation, but we can see a correlation between the number of books in your house and your potential to get a 36 [on the ACT],” Cooper said.

Reimer agrees that being surrounded by a literary environment from a young age has benefited his life.

“My parents always told me to read a book [and] not to [watch] TV or be on my phone, especially when I was a little kid. I’ve learned a lot of good lessons from it. I don’t know if I’d be the same person I am if I hadn’t read so many books when I was a kid,” Reimer said.

Yet, Reimer understands reading can be an expensive hobby and may not be suitable for everyone.

“Books are expensive, especially in recent years. It used to be [about] $15 for a paperback, [but] now it’s like $20 for just a paperback of a book; a regular book is like $30,” Reimer said.

Though money can restrict some people’s access to books, Cooper believes society, especially teachers, has an important role in bringing the books to students.

“[I heard this metaphor where] these two boys, clearly from wealthy households, asked this African immigrant boy [if he] likes golf. And [the boy] goes, ‘Well, I’ve never played it.’ And that’s [the same for] books. Maybe this African boy would love golf. [But] do you know how much it costs to be into golf? Clubs cost thousands of dollars. It’s an access point,” Cooper said. “And for books, that’s where my heart really breaks. The best thing we can do is make more literature accessible … and that’s potentially the best way to democratize access to literature.”