Tackling Tourette’s

West High students Kaylee Gibson ’23 and Ty Waters ’20 describe their experiences with Tourette Syndrome.

About Tourette’s

Tourette Syndrome is a neurological disorder involving tics, which are involuntary movements or sounds. In order to be diagnosed, individuals must have motor and vocal tics lasting more than a year, according to Tourette Association of America.

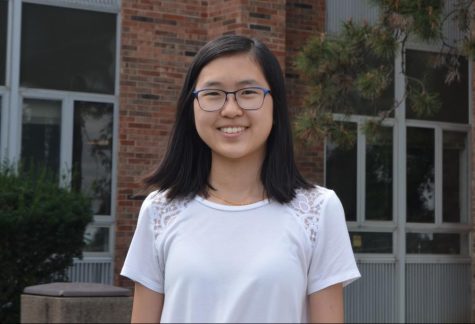

Kaylee Gibson ’23

Early in her elementary school years, Kaylee Gibson ’23 began to notice she had occasional tics, but never thought much of it. It wasn’t until junior high, when she started to develop vocal tics, that her worries started to rise. Since she developed anxiety early in life, which worsened during junior high, she initially thought her tics were anxiety-related. However, a trip to the doctor at the beginning of her freshman year proved otherwise, and she was quickly diagnosed with Tourette Syndrome, also known as Tourette’s. In her particular case, she has both motor and vocal tics, and more specifically, echolalia, which causes her to repeat phrases others say.

Because none of her family members have the condition and Tourette’s is oftentimes genetic, her tics were unexpected. However, her diagnosis brought about relief since she finally had a true explanation for her symptoms.

“I actually wasn’t too frustrated or anything,” Kaylee said. “It made me feel good that there was something actually going on, and I wasn’t just being weird.”

At first, she only openly informed a few close friends of her diagnosis. When she initially started having symptoms of Tourette’s, they helped her navigate her confusion and showed their support.

“They were just helping me emotionally, because I was like, ‘What’s going on in here?’ [and] they were like, ‘It’s okay, we still love you,’” Kaylee said.

One of Kaylee’s close friends, Tess DeGrazia ’23, reaches out to her regularly to check in. “Most of the time if she’s having some bad tics, I’ll go to her and I’ll be like, ‘Hey, are you alright?’ And we’ll laugh it off because she thinks her tics are funny,” DeGrazia said. “I think her way of coping with it is laughing it off, and I think that’s good for her.”

Through it all, her family has been the backbone of her support system. They suggested therapy to help figure out strategies to relieve her tics, and she currently focuses on containing one tic every week. Kaylee describes the feeling before a tic as a “premonitory urge … kinda like when you have an itch and feel the need to itch it,” and the tic itself as a “relief of an uncomfortable feeling.” The therapy works to target where and when she feels the premonitory urge for that specific tic, figure out its patterns and find a countermovement to eventually stop the urge.

Emma Gibson ’20, Kaylee’s sister, has noticed the toll Tourette’s has taken on Kaylee’s mental health. This became more apparent as Kaylee got older.

“As she grew up she got a little bit more reserved, and then recently she’s had lots of problems with anxiety and just all of those things that normal teenagers feel, but she feels them more strongly,” Emma said.

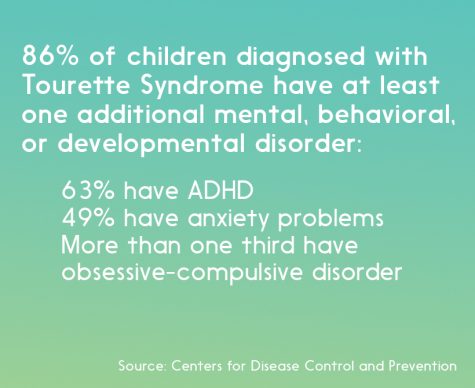

With Kaylee’s anxiety and more recent development of obsessive-compulsive disorder adding up, she has come to Emma in times of need.

“There’ve been times when she’s been having a big tic attack and she’ll just text me and say, ‘I need to come to sit by you,’” Emma said. “I think just having a presence that understands what’s happening and won’t judge her for anything she does [helps].”

However, not everyone is understanding of Tourette’s. Kaylee believes the media has pushed the stereotype that individuals with Tourette’s swear frequently, and many assume this applies to her case as well. In reality, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, only around 10%-15% of individuals with Tourette’s swear involuntarily. There have been many other instances where others make assumptions without understanding her situation.

“I’ve been told many times to be quiet during class, and it’s frustrating because I’m trying,” Kaylee said.

She often tries to suppress her tics, and some of her strategies include wrapping her legs around chairs to prevent stomping and keeping her arms straight to avoid punching. However, she often finds her attempts unsuccessful in the long run.

“Something that’s used a lot of the times for people [without Tourette’s] to connect with [suppressing tics] is trying not to blink,” Kaylee said. “You can hold back a blink for a little bit, but eventually you just have to blink.”

Additionally, people have assumed she is faking her tics, and in one instance, she was imitated by a classmate when having a motor tic. When going to crowded public areas where others don’t know her condition, Kaylee often prepares beforehand to know what to expect, especially in the possibility of a panic or tic attack.

“It’s definitely something she’s had to overcome and learn to not care about what other people think,” Emma said. “I think she’s still working on that.”

Though she faces judgment from others around her, Kaylee has received mostly positive feedback from her teachers and classmates.

“I’ve walked into class a couple times and approached a teacher and said, ‘Hey, I’m having a bad day today,’ just as a heads up, and they’ve been totally fine with it,” Kaylee said. “They’ve even pulled a couple students aside to tell them what was going on with me.”

She eventually became more comfortable with her Tourette’s and began to openly inform others about her condition.

“I realized that most people are probably going to be fine with it, they’re not gonna be mean about it as much as I thought they were gonna be,” Kaylee said. “I realized that if I just tell people outright, then it’ll probably be better.”

Kaylee has found the tuba as an outlet. She has noticed that when playing she doesn’t tic, so when she has a tic attack, she can turn to her tuba to find some relief. Earlier her freshman year, Kaylee auditioned for SouthEast Iowa Band Association honor band, where Emma saw a growth in Kaylee’s confidence.

“[The SEIBA audition] was really stressful for her because she could tic at any moment; she can’t control when that happens,” Emma said. “When she went into the audition, growing as a person she was able to just tell the judge, ‘Hey, I have Tourette’s and I might tic, and if I do, please just ignore me.’”

Emma noted that since Kaylee was a freshman auditioning against upperclassmen, she faced more pressure, but felt more encouraged to work harder to meet her goals. As a result, she earned second chair tuba.

“When she got in [SEIBA], I think that just solidified the fact that she can fight through the difficulties,” Emma said.

Since her diagnosis, Kaylee has learned to accept Tourette’s as a part of who she is and has become more accepting of those around her due to her heightened empathy.

“I think everything she’s gone through has made her a better person, better able to relate to other people,” Emma said. “Now she has gotten a better handle on everything that’s happened to her, and she’s a really good person.”

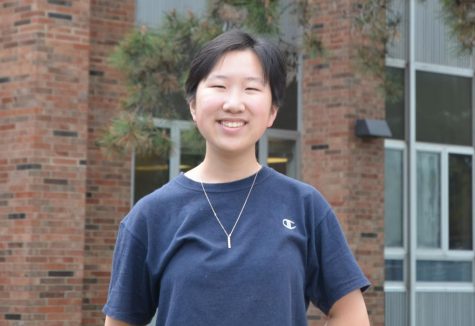

Ty Waters ’20

Before his diagnosis, Ty Waters ’20 did not understand why he was experiencing certain uncontrollable twitches. He began to notice them more frequently in the fifth grade, but because they weren’t very severe, he tended to ignore them. A couple years later, he went on the Register’s Annual Great Bicycle Ride Across Iowa. It was on that bike ride when he began to question these movements.

“It’s RAGBRAI, and you get a lot of time to think. And I was just kind of like, that’s really annoying you know, doing the whole blinking thing,” Waters said.

Waters’s symptoms include uncontrollable tics of the face and mouth and continuous blinking. However, even though he had these constant symptoms, he never understood why they happened and did not seek out an answer until much later.

“The biggest thing is that I felt alone because I didn’t know anyone else who had similar symptoms. I think that’s a big reason why I didn’t immediately say [something],” Waters said. “I was just like, ‘This isn’t really that big of a deal, so I’m just gonna keep it to myself, and hopefully nobody notices.’”

During his first years of high school at Mid-Prairie, Waters met Cooper Thomas. While the two were in class, Thomas started twitching and believed Waters had noticed. Thomas then explained what Tourette’s is and why he was having these movements. Waters described this to be the moment where he connected the dots between the condition and his own symptoms. After the interaction, Waters decided to visit the doctor, and he was officially diagnosed with Tourette’s.

“It’s honestly kind of relieving to know that other people are with you in this, [and] you’re not alone,” Waters said. “I think just having something that’s categorized and knowing that there are other people out there with Tourette’s is really comforting.”

Although Waters came to terms with his condition, others did not. Even though Waters never experienced any extreme cases of judgment, he has experienced moments where individuals haven’t been very kind or understanding. He has also seen other kids with Tourette’s be bullied for their mere motions.

“In high school, kids can be really quick to put labels on people,” Waters said. “They can be really quick to judge people on literally anything.”

Because of this, Waters was reluctant to be open with others about having Tourette’s for a long time and attempted to suppress his tics.

“At first I was just like, ‘I don’t want to be different from everyone else. I don’t want to be seen as different,’” Waters said.

Waters’s confidence grew as he transitioned into West High. He became more open and honest about his tics as others were more kind and understanding.

“I’ve always felt like the people who I’m close to here at West High are really good about accepting me because in previous environments that I’ve been at or worked at people don’t understand,” Waters said. “But here it’s different. It’s not ignorance, it’s not that people are ignoring that I have symptoms of a condition. It’s people accepting that I have a condition and not caring about it and just accepting me for who I am.”

Even if Waters couldn’t always rely on everyone to understand, his hobbies were something he could always fall back on. Waters emphasizes that there may be a direct correlation between stress and tics, but it is not a cause and effect relationship. So, whenever Waters feels stressed or is having severe tics, he relies on “The Office,” snacks and music.

“It just kind of sucks because sometimes your body is really, really tired if you are ‘ticing’ a lot. One of my tics used to be grinding my teeth a bunch,” Waters said. “And to me it’s always been, I have to find a way to get my mind on something else.”

Music is the outlet that Waters relies the most on. He first picked up the trombone during fifth grade and started to scat, or imitate jazz instruments with his voice, after hearing a particular song. Since then, he hasn’t stopped either one. He’s practiced the trombone incessantly, and has participated in marching band, Jazz Ensemble and a prestigious marching band called Drum Corps International. Waters has also participated in All-State Choir and All-State Jazz Band.

“I think it’s just something that’s constantly running through my brain. [Music] kind of found me,” Waters said.

Former West student, Thomas Duong ’19, played in jazz band with Waters and knows him as being an eccentric and quirky person. The two formed a close friendship, and Duong witnessed how Waters developed a deep connection with music. The two even meet up to play together nowadays.

“He hasn’t changed ever since I left high school,” Duong said. “I mean, I think he’s grown as a person like everybody else has throughout high school, but Tourette’s has never affected his ability at all in achieving great things.”

Because Waters never let anything stop himself from achieving his goals, he wants to let all kids know that Tourette’s does not hinder their potential for success.

“It’s really, really important for people who even think that they have Tourette’s to know that they’re not alone, and they’re not abnormal,” Waters said. “It’s something that’s normal … No one should judge you, and if they do judge you, they’re not worth being around.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Fareeha Ahmad is a senior at West High, and this is her second year on staff. She is the profiles editor for print and the copy editor for yearbook. When...

(she/her) Alice Meng is a senior at West High and this is her second year on staff. She is a copy editor and in her free time enjoys spending time with...

Brenda Gao is a junior and this is her second year on staff. She is the print Entertainment Editor and a designer. She likes playing Minecraft, painting...