Affirm or overturn

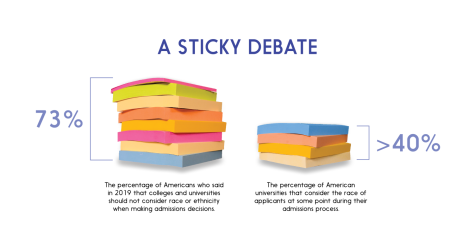

For the sixth significant time since 1974, affirmative action is under the Supreme Court’s review.

Affirmative action’s place in college admissions is under the Supreme Court’s scrutiny, with a decision likely to be released this summer.

After being instituted under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, affirmative action has played an important role in offsetting long-standing systemic discrimination. Affirmative action is a set of policies and practices that attempt to incorporate equity into job and educational opportunities by favoring those who are historically disadvantaged, such as women, racial minorities and people with disabilities. Past Supreme Court rulings have limited affirmative action’s scope, and once more, its place in college admissions is under scrutiny.

During the week of Oct. 31, the Supreme Court heard arguments against the legality of Harvard University and the University of North Carolina’s race-conscious admissions policies after the two cases were filed separately in 2014. Students for Fair Admissions, a nonprofit group of over 20,000 students and parents that advocates for eliminating the consideration of race in college admissions, initiated both cases. The organization alleges that by evaluating subjective measures like courage, likability and kindness in prospective students, Harvard creates a cap on the number of admitted Asian students and engages in discriminatory behavior. The case against UNC argues that the university discriminates against white and Asian students due to a preference for Black, Hispanic and Native American applicants. Harvard denies discriminating against Asian students, and both universities responded that race-conscious admissions policies are lawful under Supreme Court precedents.

If affirmative action is overturned or restricted, the consequences will reshape the college admissions process, affecting both applicants and universities alike.

Precilia Kangni ’24 supports affirmative action and, as a Black student, recognizes how it helps her chances of getting into college, especially when competing against those who are more privileged.

“Historically, people have been marginalized because of race or class,” Kangni said. “Affirmative action is meant to give people who do have those disadvantages a chance … a leg up to being put down for so many years.”

However, Kangni believes race should not be the key determiner in one’s acceptance, but should instead be viewed within the context of a holistic admissions process.

“[Race] shouldn’t be seen as something colleges should meet as a quota,” Kangni said. “It should be considered [the same] as a college essay is considered … a part of who you are.”

Although she hasn’t yet applied to college, Kangni has already experienced the benefits of affirmative action firsthand. Last summer, she attended a competitive program for rising high school juniors at Carleton College that explored the “African American Experience” and life at a liberal arts institution.

“Having those opportunities where previously it wouldn’t [have been] offered like it is now … is what makes affirmative action so positive and [have] such a big impact on people’s lives because of how disadvantaged they could be without it,” Kangni said.

Supporters of affirmative action argue it encourages upward mobility and diversity on college campuses. Still, race-conscious admissions policies can be seen as discriminatory toward one minority in particular: Asians.

A 2009 Princeton University study found that Asians applying to extremely selective institutions faced odds six times as high as similarly-qualified Hispanics and 16 times as high as Black applicants. Further, on the SAT, Asians must score 270 points higher than Hispanics and 450 points higher than Black students (on a scale of 1600) to have an equal chance of admission to high-caliber universities.

Derrick Pennell ’24 recognizes that being Asian places him at an academic disadvantage when applying for college. Consequently, he believes that affirmative action largely doesn’t have a place in a fair college admissions system.

“It comes down to whether or not colleges should sacrifice their diversity in order to pick only the students who show the most potential, or whether they keep their diversity, but potentially exclude a bright student,” Pennell said. “[Removing affirmative action], technically speaking, would provide an equal chance for all races because race wouldn’t be even considered.”

Kangni believes the higher standard placed on Asian applicants isn’t a fault of affirmative action, but instead of the Model Minority Myth, which is the stereotype that Asians achieve more than other minorities due to inherent talent and strong work ethic. Kangni believes the execution of affirmative action should be improved by not believing harmful stereotypes.

“There’s not one way to be Asian and one way to be Black. Having this unrealistic expectation that all Asian people are smart or academically gifted is not good,” Kangni said. “It’s the stereotypes that play into using affirmative action as a way to push agendas that are discriminatory.”

Pennell agrees that there is a generalization of academic excellence targeted at Asians.

“There’s the stereotype of Asians being smart,” Pennell said. “[Affirmative action] is at the detriment of Asian and white students … not all Asians rise to that same expectation.”

With a 6-3 conservative Supreme Court majority likely to release a decision this summer, affirmative action’s end seems imminent. How to ban race from college admissions then becomes tricky. For example, students may no longer be able to discuss their experiences with race in college essays.

Kangni views the personal essay as a crucial aspect of any student’s application, and she currently plans on writing about her identity as a Black person. If race can no longer be disclosed, Kangni feels as though she wouldn’t be able to express her full, authentic self in her essays.

“[In my essay], I would talk about struggles and just living as a Black person, but that doesn’t mean everything is a struggle,” Kangni said. “I can’t be raised as who I am and then talk about who I am as a character and not bring up race.”

Although students are allowed to reflect on their race in college applications, Asian students are sometimes discouraged from doing so. A New York Times investigative piece documented a common phenomenon where Black and Hispanic students are encouraged to emphasize their race in applications, but Asian students are advised to stray away from activities or narratives perceived as classically Asian.

“I find it a bit sad [that] Asians have to hide part of their identity because it’s seen so much, while other races get to showcase their heritage because it gives them an advantage,” Pennell said.

If affirmative action is repealed or its influence limited, Black and Hispanic students will face another barrier in their pursuit of higher education, and college campuses will lose diversity. But if race-conscious policies are affirmed, Asian students will continue to be disadvantaged, as they bear the burden of a higher standard of excellence. Pennell acknowledges the issue is complex and without an easy resolution.

“Every solution we make to help one or more groups just seems to be at the detriment of another,” Pennell said. “No matter what the Supreme Court decides, this truly appears to be a no-win situation.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

(she/her) Lilly Graham is a senior at West, and this is her third year on staff. Lilly is the Managing Editor for the print edition. Outside of school,...

(she/they) Sachiko is a senior at West, and this will be their 3rd year on staff. She is a design editor and photographer for the print publication. In...