Fake rank

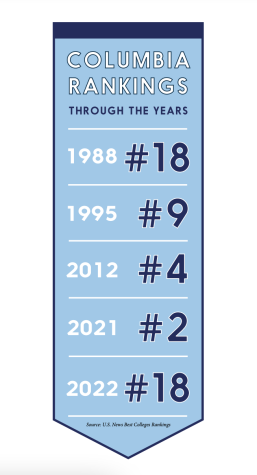

After submitting false data the previous year, Columbia University dropped from second to 18th in the 2022-2023 U.S. News Best National University Rankings, calling into question the accuracy and merit of college rankings.

WSS explores the Columbia University ranking scandal and the role prestige plays in students’ college applications.

In February, tenured Columbia University math professor Michael Thaddeus published an investigation challenging the accuracy of data Columbia submitted to the U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges rankings. In his investigation, Thaddeus described the data as “inaccurate, dubious or highly misleading.” Columbia, after being removed from the 2021-2022 ranking due to Thaddeus’s report, withdrew from the 2022-2023 rankings and later admitted to using dated or incorrect methods to determine some of its data points. U.S. News responded by relying on its own calculations, along with federal data, to place Columbia as the 18th-best university in the country. This was a staggering demotion from the 2021-2022 school year when Columbia was tied for second with Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

William Zhang ’20 is a current junior at Columbia studying computer science. Although Zhang was disappointed to learn that Columbia’s administration had doctored numbers to improve its standing in the college rankings, he wasn’t shocked.

“It shouldn’t come as such a surprise that they dropped in the rankings,” Zhang said. “There are a lot of issues with undergraduate education at Columbia that I feel like you shouldn’t have to deal with if you’re going to the supposedly second-best school in the nation.”

Zhang cites overcrowding as a major problem on campus. A March 2022 report by the Columbia Spectator, a news organization run by undergraduate students at Columbia and Barnard College, found that there are nine Columbia students on a meal plan for every seat in the dining halls. Thaddeus also questioned the university’s former position on class sizes. Columbia initially claimed that 83% of its undergraduate classes enroll under 20 students per class when in reality that number is around 57%.

Due to overcrowding, Zhang was unable to take the classes he wanted during his first three semesters at Columbia, even if they were required for his major. Once he got off the waitlist and was able to enroll in a computer science class, Zhang’s first in-person lecture was overfilled.

“The first day [of computer science] was [in] September 2021 when there was still COVID-19 in New York City,” Zhang said. “It was a packed auditorium. There were people sitting in the aisles of the classroom just to be able to hear the lecture.”

Zhang believes that disappointment over the ranking scandal was a common feeling among his peers, who have long been frustrated with Columbia’s administration.

“The general sentiment toward the Columbia administration has always been negative,” Zhang said. “[The administration] seems to only try to find ways to earn more money with little regard for the students or community. This scandal seems to be the latest instance of the administration being shady.”

Dana Rolander, a private college coach at Midwest College Consulting, believes submitting misleading data for college rankings likely isn’t unique to Columbia.

“Colleges have long been suspected of and found manipulating data to improve their position in the rankings,” Rolander said. “I think Columbia’s long-standing Ivy [League] reputation is safe; I think the reputation of the rankings is more likely to suffer than Columbia’s.”

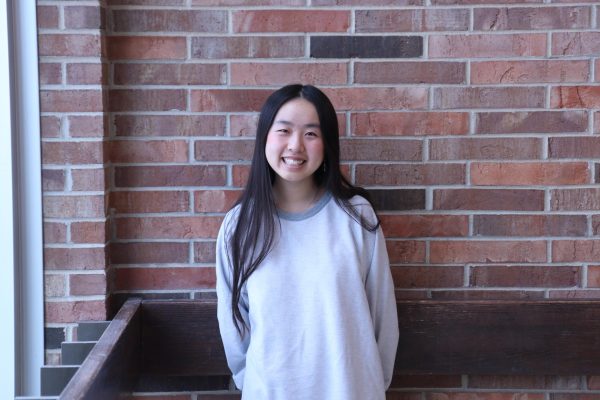

Senior Ashley Seo is applying to Columbia and also suspects other colleges are guilty of submitting false data to improve their status.

“I think all the top colleges would do something similar [by] tweaking their rankings,” Seo said. “They just don’t have a professor who is going to release it to everyone else in the world.”

Rolander holds that the accuracy of college rankings is undermined because schools self-report data which can hinder reliability and transparency. Additionally, Rolander describes how schools can easily manipulate statistics like acceptance rates. For example, selective universities can encourage unqualified students to apply to their institutions in large numbers and then reject these students, lowering acceptance rates. Further, schools may defer acceptance to lower-caliber students until the spring term; as a result, their statistics, like test scores, aren’t reported with those of the incoming class.

Considering the misleading nature of college rankings, Rolander believes a college’s rank and perceived prestige play an overly important role in students’ decisions about where to apply for college.

“I think getting into an elite school can feel like an acknowledgment or a reward for hard work,” Rolander said. “I feel that students should be open to the mindset that the reward doesn’t need to necessarily come in the form of an invitation to an elite institution.”

Zhang was initially drawn to Columbia because of its core curriculum, a set of courses involving history, philosophy and literature that all undergraduates must take in order to achieve a solid grounding in the liberal arts. However, he admits the one of the biggest factors behind his college search was how prestigious colleges were, a drive he feels is common at West High.

“I regret how much I cared about getting into a prestigious institution,” Zhang said. “[West students are] probably familiar with the immense pressure everyone feels about applying and getting into target universities. I think a huge part of that pressure is a feeling that one’s self-worth and intelligence is tied to how good of a school one attends.”

For Seo, however, ranking isn’t the central factor determining her college application process. As someone who has lived in Iowa City most of her life, Seo is interested in Columbia because of its location in New York City. Additionally, Columbia is one of few schools that offers her desired major, financial engineering. Nonetheless, Seo does recognize that some of her peers may apply to an institution solely because of its reputation.

“I feel like a lot of people just apply to the top ten schools and the Ivy League to see if they can make it, not even because of interest,” Seo said.

The West Guidance Department advises taking a more individualized approach throughout the college search that places less emphasis on a college’s ranking.

“While rankings can provide valuable information, they do not tell the story of whether or not [a college] is actually a good fit for the student,” the guidance department wrote via email. “When we advise students, we do not look at how the college ranks. We focus on meeting students’ needs.”

With her clients, Rolander uses college rankings as a resource for college ideas but not as a key factor dictating where students should apply.

“I think college advisors have long discouraged families from placing too much weight into the college rankings,” Rolander said. “The data points themselves are not necessarily relevant to what makes a particular college better than another for any one student.”

U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges rankings, considered the gold standard of college rankings, evaluated 1,500 institutions across 17 metrics in their 2022-2023 edition. Based on how well a college performs across individual categories, it receives a weighted score on a scale of 0-100, with 100 as the highest score attainable. Graduation and retention rates, undergraduate academic reputation and faculty resources are the three categories that hold the most weight in determining a school’s score. Columbia’s fabricated data largely fell under the faculty resources umbrella, regarding both class sizes and the percentage of faculty with the highest degree available in their respective fields.

Rolander, instead of relying on college rankings, emphasizes the importance of how well a school fits a certain student with consideration to a variety of factors like location, academics and financial aid programs.

“What can you afford? How rigorous is the curriculum? Is it a culture that you feel comfortable in?” Rolander said. “The rankings are not going to tell you most of those things. I think it’s really important to dig deeper when you’re looking [for colleges].”

Rolander believes Columbia’s ranking scandal brings publicity to the inherently manipulated and potentially inaccurate ranking system.

“I think that the best thing that’s happening, for families and students especially, is that attention is being drawn to rankings and that Columbia did get caught with their hand in the cookie jar,” Rolander said.

Like Rolander, Zhang hopes that Columbia’s misconduct will prove educational by demonstrating the irrelevance of a university’s ranking.

“My ultimate goal is that because of ranking scandals like these, people will put less emphasis on the ranking of universities and consider universities as places to get educated and meet people … not as fancy names to flaunt around,” Zhang said.

Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

(she/her) Lilly Graham is a senior at West, and this is her third year on staff. Lilly is the Managing Editor for the print edition. Outside of school,...

(she/her) Jane Lam is a senior at West High. This is her third year on staff reporting for the print publication. As an assistant copy editor, she loves...