We all have that one fictional character we can find ourselves relating with. Or two. Or a couple of dozen. It doesn’t matter what role they play. Maybe they’re the protagonist or the love interest—and sometimes they’re the villain or monster.

While it only feels that queer representation has just been getting some spotlight for the past few years, it’s been around for generations, just taking on a different form. If you were to ask me which fictional character on television I can relate to as queer, my first thought wouldn’t go to some “Heartstopper” character; I’d probably respond with Remus Lupin, the werewolf from “Harry Potter.”

Archetypes are a common tool used when writing characters that make them easier to understand for the audience and help them seem relatable. Certain personality traits lead to certain tropes, leading to formulas that are simple to digest. Sometimes, however, these tropes can be a gateway into writing problematic stereotypes or surface-level characters; take the token Black friend or the mean popular girl, for example.

The issue that arises from this is that often; these tropes involve assigning specific demographics to the same roles, allowing the audience to associate certain traits and characteristics with said demographics. Black people are clueless and superficial; women are manipulative and vindictive. Media is often the reason why people have a tendency to view other demographics in a certain light.

When it comes to the queer community, there are many layers to the representation seen on screen. This demographic, in particular, falls into a strange position where the characteristic that sets them apart from “everyone else” is something that doesn’t exactly show on the face, such as skin color or biological sex. In the sense that anybody could be LGBTQ+ without saying it makes showing it a peculiar conundrum.

Apart from the typical “gay” stereotypes that have infiltrated screens for decades, with the supposed “gay voice” and clothing choices, the queer community also has more subtle ways of appearing on screen. Naturally, like any other minority, the queer community’s presence in television over the years is better described as invisible than anything, but at the same time, sometimes it’s all about having a trained eye.

The idea of queer coding is when fictional characters can be read queer when looking at the subtext, whether implied by the creators or unintentionally included. Sometimes, it’s as obvious as Him from the “Powerpuff Girls” in his stylish drag outfits and sultry voice, but never actually confirmed as LGBTQ+. Or sometimes you have to analyze more carefully, like with the titular character of “Ted Lasso,” who, although was canonically married to a woman, his love of musical theatre and Freddie Mercury mustache could strongly be interpreted through a bisexual lens.

Headcanoning fictional characters has been a long-standing practice in the fandom community, especially when the character in question feels particularly relatable for LGBTQ fans. Some may refer to it as projecting, but when people are starved for representation, they’ll pick up even the smallest detail to confirm their suspicions. If a character wasn’t confirmed cishet, they might as well be bisexual, pansexual, nonbinary, and the list goes on. If a character resonated with us even for a moment, they were queer in our hearts. The subtleties were never lost on us.

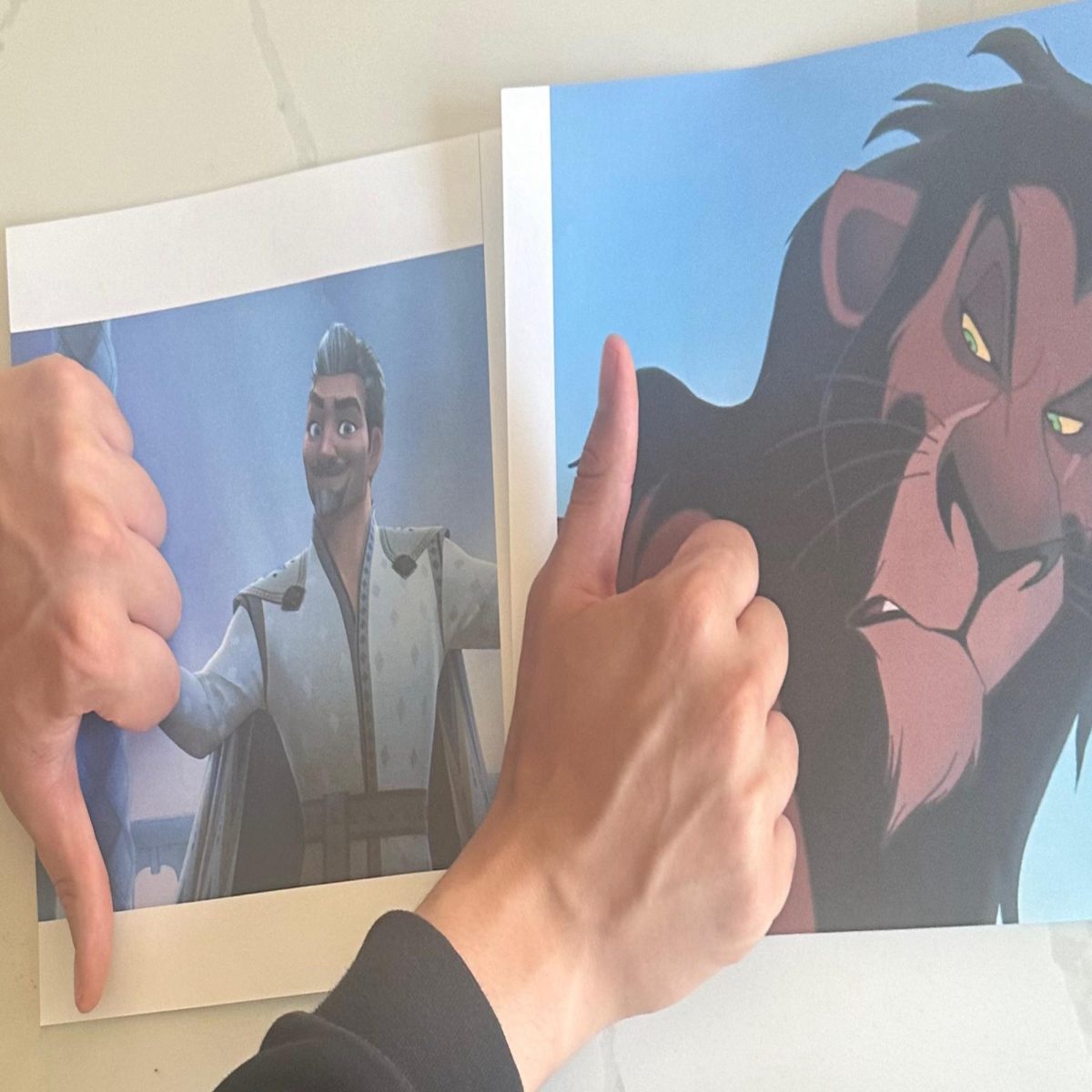

If we were to go back even ten years ago, there was a certain pattern to characters that were being coded as queer. Disney, specifically, has a long history of attributing villains with traits that often were perceived as queer at the time. Captain Hook, Jafar, and Scar, all of these iconic villains, when compared to their masculine counterparts, appear sassy, flamboyant, and feminine—all negative stereotypes towards gay men. And because they’re the bad guy, they also seem predatory and dangerous. Even Ursula was inspired by a real-life drag queen, referred to as Divine. It shouldn’t be said that any of this was a coincidence.

Even farther back in history, the implications run deeper. Horror is renowned for the queer lens placed on much of its media. Alfred Hitchcock, one of the most influential horror and thriller movie directors of all time, is also known for including various queer elements in his films and, thus, making said well-known horror movies queer-coded. “Rope” notably suggests a chemistry between the two main criminals, and “Rebecca” strongly hints at something with its titular character.

Queer people, often demonized by society, were the perfect tool for a genre that was often socially-critical. The unfamiliar makes most people uncomfortable, and what is more unfamiliar to cishet people than people “unlike” them? The abnormalities. The freaks. They don’t understand queerness, so they are frightened of them; probably part of the reason why Hitchcock so often enjoyed exploring such themes in his works. “Rocky Horror Picture Show” does it best as a satirical depiction of how the heteronormative narrative can transform queer people into these inhumane, sexually-depraved beasts when said characters are unapologetically their true selves. These were the horrifying creatures queer people were forced to see themselves in.

Queer cinematic history is a fascinating topic to look into. It’s easy to just sum it up as movies depicting queer people as monsters is a bad thing, but we can give that viewpoint more depth. It’s more important to acknowledge that back then, people were just as aware of our existence as they are now. We can choose to reclaim this narrative of queer people being monsters and change it instead to people viewing queer people as monsters because of their own fears. That way, it invites a more inclusive narrative.

In our current day, there has been a kind of reclamation for these outdated stories. Scared of us or not, we don’t need to seek validation or acceptance— instead, we just want to proudly show who we are. The community has taken these films that are supposedly trying to villainize us and has turned them into cult classics because we can celebrate who we are now.

The parallels between the queer experience and being the villain are undeniable—outcasted by society, hiding and wearing masks, treated as the deviants of society— mirrors of each other. When it comes to representation, it’s not necessarily inaccurate. Just small-minded. There is more to us than just an archetype and a couple of common traits. As much as we’d like to believe that queer people are innocent, perfect angels—we’re just human with human flaws. We can be villains as well as heroes. And frankly, heroes can be boring.

As the joke goes, “I support gay rights and gay wrongs.”