When the people shall have nothing more to eat, they will eat the rich.

— Jean-Jaques Rousseau

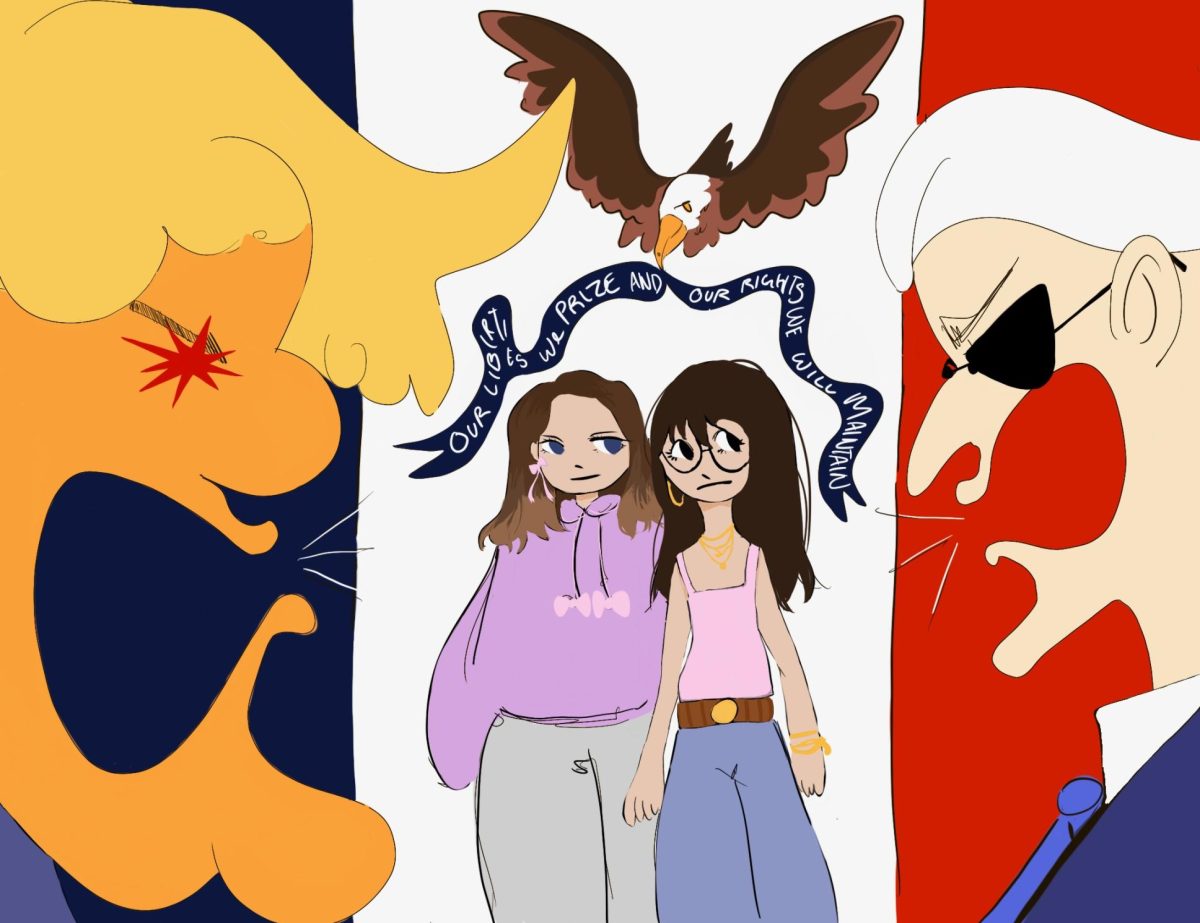

In recent years, the eat-the-rich storyline has become a prolific narrative that has been taking over the entertainment industry. Traced back to the French Revolution, the phrase “eat the rich” was originally a political slogan that protested against heavily capitalist economies that attributed to wealth disparity and class inequality. For as long as humans could read and write, people have used storytelling mediums in order to express criticism toward the privileged 1%, but it is only lately that the concept of eat-the-rich has become a distinct genre in media.

From Oliver Twist to Batman, commentary on wealth vs. poverty has been a consistent staple in writing throughout all time. Whether it’s to shed light on the struggles of the working class, to point out the corruption of the privileged, or just to hold a mirror to society to show what we’ve come to, it’s hard to escape the burden of money, even in fiction. You find it in the stories following the life of royalty in a fantasy kingdom, watching a group of robbers pull off a heist worth billions of dollars, or cheering on the blossoming love between a struggling grad student and the powerful CEO—you simply can’t avoid how much influence this narrative has in storytelling. But these kinds of stories clearly aren’t meant to be interpreted as eat-the-rich. So what does?

Whether it’s to shed light on the struggles of the working class, to point out the corruption of the privileged, or just to hold a mirror to society to show what we’ve come to, it’s hard to escape the burden of money, even in fiction.

— Nicole Lee

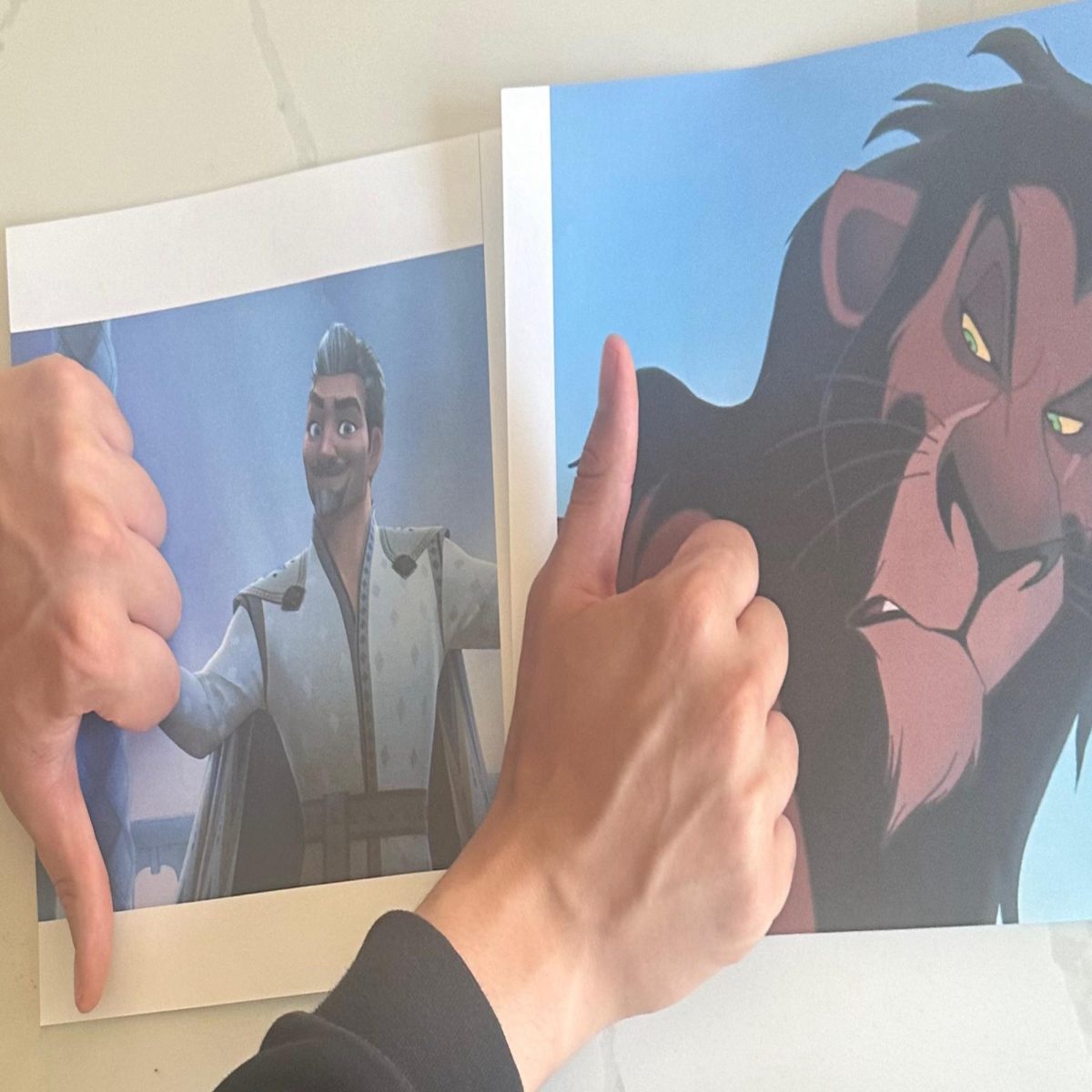

The root of all evil is material wealth. Eat-the-rich films make this very clear. The true villains in these stories aren’t those who commit the heinous crimes but, instead, those who push these people into that corner in the first place. These scenarios can be depicted in either comedic or dramatic fashions, defined by the sentiment of wanting to give the upper class their due. Either way, graphic violence is often included to put the privileged in a negative light as a way of fulfilling an almost violent fantasy and making the intention crystal clear — because sometimes it takes blowing up a billionaire’s private island in Greece or burning down your prestigious restaurant and all its inhabitants dressed as s’mores for some people to get the point. Overall, eat-the-rich films are vengeance stories—justice for those who’ve been suffering under the weight of the rich’s egos for too long.

The true villains in these stories aren’t those who commit the heinous crimes but, instead, those who push these people into that corner in the first place.

— Nicole Lee

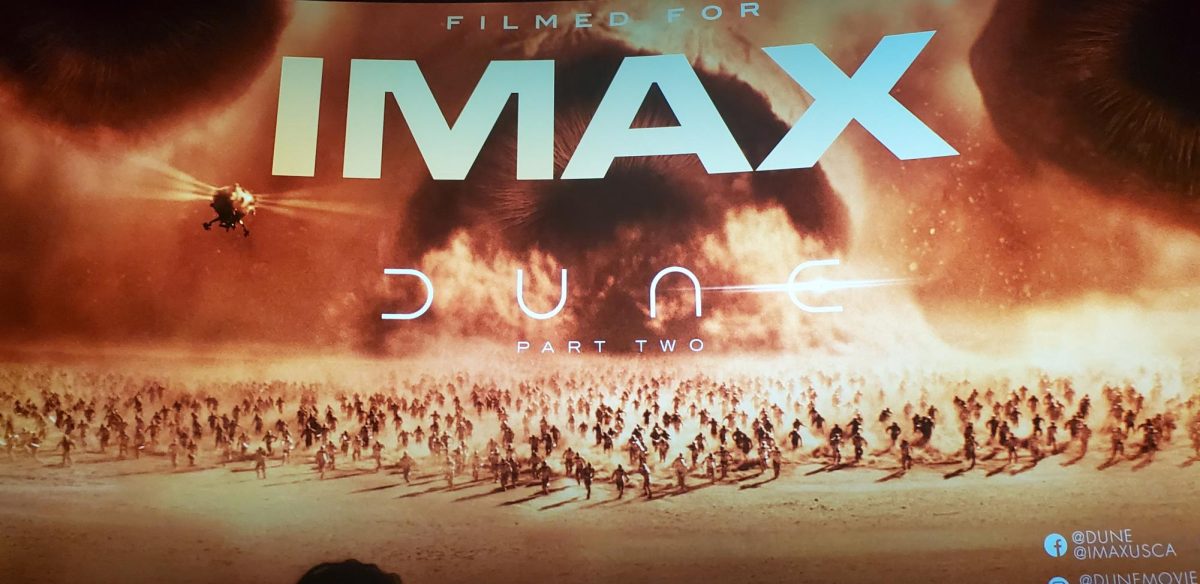

And while these films might be cathartic to watch, nothing is immune to the ever-falling trap that is capitalism. When a film criticizes the unfair advantage the wealthy have over the rest of us, it is the same film that grosses millions of dollars at the box office, profiting from the very system it villainized. Hollywood has been pumping out eat-the-rich films like never before, and while that might reflect the current state of our economy, it also brings to question if the purpose of these films has been lost on us. It’s saddening how easily it was for capitalism to take advantage of the very thing that tries to question it simply by throwing money at the problem. If you benefit from the very thing you advocated against, how much of a difference or impact have you really made?

It’s saddening how easily it was for capitalism to take advantage of the very thing that tries to question it simply by throwing money at the problem.

— Nicole Lee

People went crazy when “Saltburn” first hit theatres, obsessing over the glamorous Brideshead aesthetic of Saltburn manor as well as the homo-erotic tension between Barry Kerogen and Jacob Elordi (with that height difference, who wouldn’t?). But perhaps the gorgeous cinematography and outrageous performances (Bathtub. Vampire. And tombstone. Need I say more?) have distracted from the lack of substance the film attempts to offer as a satirical commentary toward social class.

A big part of the reason “Saltburn” can’t be categorized as eat-the-rich is because, as unlikeable and out-out-touch as the Catton family tends to be with their passive-aggressive remarks and callous way of tossing money at their problems, they’re also harmless. Although Oliver does succeed in consuming the affluent Catton family whole, it is out of his own greed and desire to be more rather than wanting payback for being wronged in some way. Eat-the-rich films are all about showing how many people can suffer because of the ignorance or arrogance of the rich, which “Saltburn” barely accomplishes, especially considering that its main protagonist never technically came from a place of struggle himself and was just as selfish at the rich people he overthrew. It doesn’t help the fact that the film’s director, Emerald Fennell, who was also raised as an elite from birth, which calls to question if she’s really in the position to be making these criticisms on classism.

But despite not technically being eat-the-rich, the film does highlight the paradox that many popular eat-the-rich films find themselves in. The hedonistic nature and atmosphere of “Saltburn” accomplishes in seducing the viewer to the comfortable lifestyle of the Cattons, which is necessary to show how Oliver falls in love with Saltburn. However, this romanticized view of the rich is part of the problem.

While people praise the idea of overthrowing the rich in order to make grounds more equal, we also can’t help but romanticize the wealthy lifestyle, fantasizing about the idea of living like royalty, where the biggest drama in your life is how you’re going to spend your holidays. This is why eat-the-rich films, and frankly, all other media, lean into the aesthetic despite everything. Because, in the end, that’s what sells. The temptation is too strong. And thus, the hero becomes the villain, and we become the very thing we swore to destroy.