I’ll be honest; my main motivation for writing this is because I want to argue my right to sing this song to myself without feeling like I’m promoting date rape.

When Frank Loesser composed this jazz-infused melody back in 1944, it was never intended to become the popular Christmas ditty it is today. Instead, it was a playful schitck performed as a duet with his wife at the end of their parties. In fact, contrary to the lyrics of a man urging a woman to stay, they used to sing in order to signal the end of the night and politely inform guests that it was time to head home. Despite this simple origin, “Baby, it’s Cold Outside” went on to win the Academy Award for Best Song in 1949 and was named one of the 100 best songs of all time by TIME magazine, earning its place as a holiday classic.

“Baby, it’s Cold Outside” has long stirred controversy for the double entendres found in the lyrics way before #MeToo began to complain. In the uptight, conservative decade that was the 40s, people were often offended by the song’s risque meaning, getting it banned on several radio stations. Nowadays, the main complaint towards the song seems to be towards the lack of consent the song seemingly portrays.

Lyrics such as “Say what’s in this drink?” or “I ought to say no, no, no sir,” have been interpreted to depict a date-rape scenario where the singer in question has just been drugged by the man urging her to stay, using the weather as an excuse to delay her departure. While this is certainly a dark take on what was a party song, it’s unfair to label something as problematic without doing the proper research. It still grates my gears every time someone insists that Spirited Away is actually a metaphor for child prostitution just because one fan theory happened to take off. Can we not let some things stay innocent for once?

Susan Loesser, daughter of Frank Loesser, has publicly defended the song in the past, stating the line about asking what is in the drink is referring to the alcohol content rather than a reference to being drugged. This was during an age when consent was a tricky business. Playing “hard to get” was the expectation for all women towards any romantic advances, whether welcomed or not, since they were always responsible for keeping the line from being crossed. And men were encouraged to push on even if “no” was explicitly said. Subtlety was key, and all sexual desires were to be kept secret.

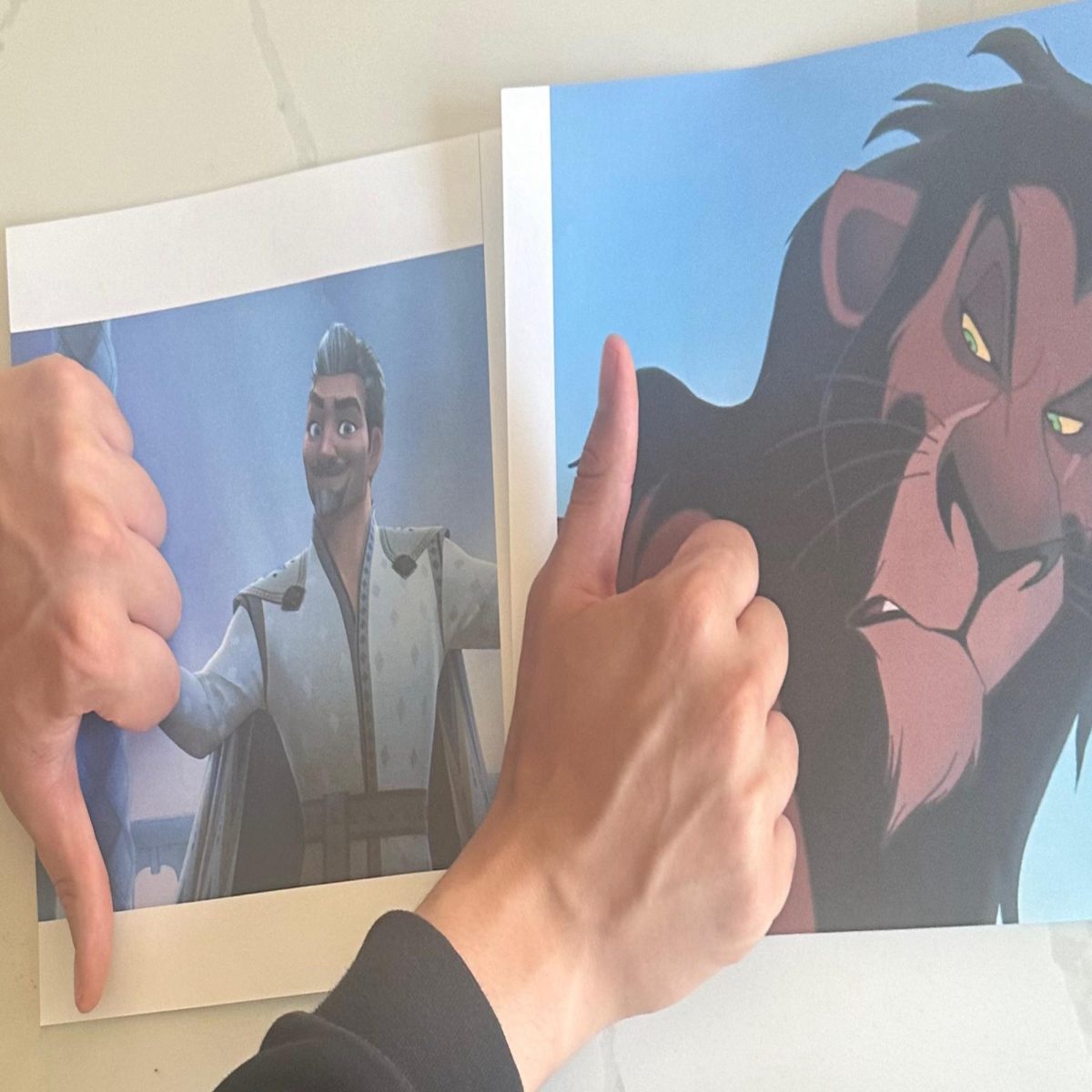

It should be noted that even from the very first time the song debuted in the movie, “Neptune’s Daughter,” context was everything. In this instance, the song was sung by two separate duets, Ester Williams with Ricardo Montalban and Betty Garrett with Red Skelton. For the first pair, the song was performed in the traditional manner, with Williams trying to fight off Montalban’s insistence for her to stay longer.

On the other hand, the movie turns the table on us with the second pair by having Garrett be the one to urge Skelton to spend more time with her (my favorite part of this twist is during the infamous “what’s in this drink” line, where Garrett’s upfrontness flusters Skelton so much that he drinks from the flower vase instead without realizing).

And then, the song is once again flipped within the same number when Skelton manages to leave, realizes it’s, in fact, his house he’s departing from, and comes back inside to try and respectfully get Garrett to leave for her own sake while she tries to convince him she’d “freeze out there.” This gender swap just shows the teasing intention of the song and, more importantly, how consensual. In both cases, all parties did want the other to stay; they just knew how to be coy about showing it.

Then, in 2019, all of the subtleness was lost with John Legend’s and Kelly Clarkson’s rewrite of the song, including a more PC version of the lyrics, where direct consent is the key. This version of the song may be considered more “politically correct,” however, perhaps just as controversial. It’s very much in your face about respecting boundaries, and did everything short of outright calling out the original song for its “problematic” nature, even using the line “your body, your choice” as if it wasn’t clear enough that these lyrics are supposed to be progressive. Many went out of their way to argue that it wasn’t in the artists’ right to revise such a classic song and the online debate was reignited.

I cringed when I first heard this remake. Not because what they were trying to promote isn’t necessary or untrue, but just because a song from the 1940s aged poorly doesn’t mean it has to be revised for the general audience. That isn’t being progressive; that’s ignoring and erasing the historical significance.

Concepts like the #Metoo movement are not about rewriting history; they are about acknowledging the past and learning from it. While perhaps that’s what these new lyrics were trying to accomplish, it blatantly overlooks how the original represents an entire age where men and women alike were entering a point where casual relationships and dating were becoming the norm and how pursuing things like sex and intimacy were gradually becoming more accepted. If that’s not progress, what is?

In the end, the real injustice towards this song was trying to find more meaning where there isn’t. Reading into things and then ignoring what’s on the surface is the real cause of this misunderstanding. Frank Loesser probably never intended for his playful duet to become part of such a charged debate; he just wanted something to help the lull in the party. So feel free to sing this song to your heart’s content, blast it on the stereo, and don’t feel like you’re contributing to a history of date rape and non-consent. Remember, your playlist, your choice.