“As I’ve already said, at a minimum the town is a Utopia. I can walk to everything, and everything’s cheerful and clean.” – Kurt Vonnegut about Iowa City in a letter to his wife, Sept. 24, 1965.

In 2008, Iowa City received the designation of a UNESCO City of Literature, becoming the first City of Literature in the United States. There are only 53 Cities of Literature around the world including places like Dublin, Jakarta and Milan. Seattle is the only other UNESCO City of Literature in the United States.

In order to become a UNESCO City of Literature, several criteria must be met, including an application that must be submitted and then reviewed. After receiving the designation, Iowa City is now able to boast their reputation of being a City of Literature.

In order to maintain Iowa City’s designation, a nonprofit was established in 2009. Currently overseen by John Kenyon, the nonprofit organizes events like One Book, Two Book and the Iowa City Book Festival. “We communicate with and collaborate with other cities in the network and communicate with UNESCO and just generally try to elevate the literary culture here in the Iowa City area,” Kenyon said.

A Des Moines native, Kenyon first came to Iowa City as a journalism student at the University of Iowa. “The main reason that I have stayed here is because I’ve really fallen in love with the culture of this community, and a huge part of that is the writing,” Kenyon said.

Kenyon seeks to add to this culture by providing literary opportunities for children. One Book Two Book, a writing competition for 1st through 8th grade students. Each February, the winning students are invited to the “Write Out Loud” event.

The One Book Two Book website cites their mission to shine a light on the literary talent present in K-12 schools. “Recognizing and celebrating this talent is a big reason behind the City of Literature organization’s annual One Book Two Book Children’s Literature Festival,” their website reads.

Kenyon agrees with this statement. “Everybody knows who scores the winning touchdown of the Big City West football game, but writing is a really individualized and sometimes solitary pursuit,” said Kenyone. “So we like to think that we can give people an outlet for how to share their work and how to get feedback and how to be recognized when that work is exemplary, and try to foster that feeling that writing matters.”

While the City of Literature label is fairly recent, the literary history of Iowa spans decades. World-renowned author Kurt Vonnegut lived in Iowa City, teaching there for a short time. The Iowa City Public Library has copies of his journals and correspondence from his time in the city.

Chris Lafave, the curator for the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library spoke of the impact Iowa City had on Vonnegut. “When he found himself in Iowa City, he found a little bit more free time to write,”

The most famous book of Vonnegut’s is ‘Slaughterhouse Five’ which is a semi-autobiographical discussion of his time serving in World War Two, especially how his perception was shifted after the bombing of Dresden.

His anti-war views in the book are widely controversial, having faced countless bans. One time of note took place in 2012, in Republic, Missouri, where a professor attempted to ban the book on the grounds of profanity and sexual content, according to the Atlantic.

After the ban took effect, the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library opened a form on their website where students can request a free copy of the book. “He demanded they remove it. When they did, we began mailing free copies of Slaughterhouse Five to the kids who wanted to read it.” Lafave said.

The matters of free speech and freedom from censorship were core beliefs of Vonnegut’s, and the Museum and Library seeks to continue this mission. “So when you talk about ideas that are unpopular, that maybe makes people not want said work of art to exist, or work of literature to exist.” Lafave said.

However Lafave postulates that these darker topics are crucial to the development of a well-rounded reader and citizen. “I think we have genuine concerns about a society that does not read depressing literature, where students in school are not, at least at some point, required to read literature that depresses or upsets them. There’s the concern that if you never read anything depressing or upsetting, we won’t have an educated society or functional society.”

Kenyon shares his concerns with the recent rise in book bans. “That’s been a big part of what we have done as an organization, too, is advocacy around those issues and trying to keep people informed as much as we can… We work with the folks here at the library a lot on those types of issues, and just trying to find ways that we can make people aware of what’s going on and try to provide them tools for how they can contact elected officials or just get word out about what they’re thinking and feeling about these things happening.”

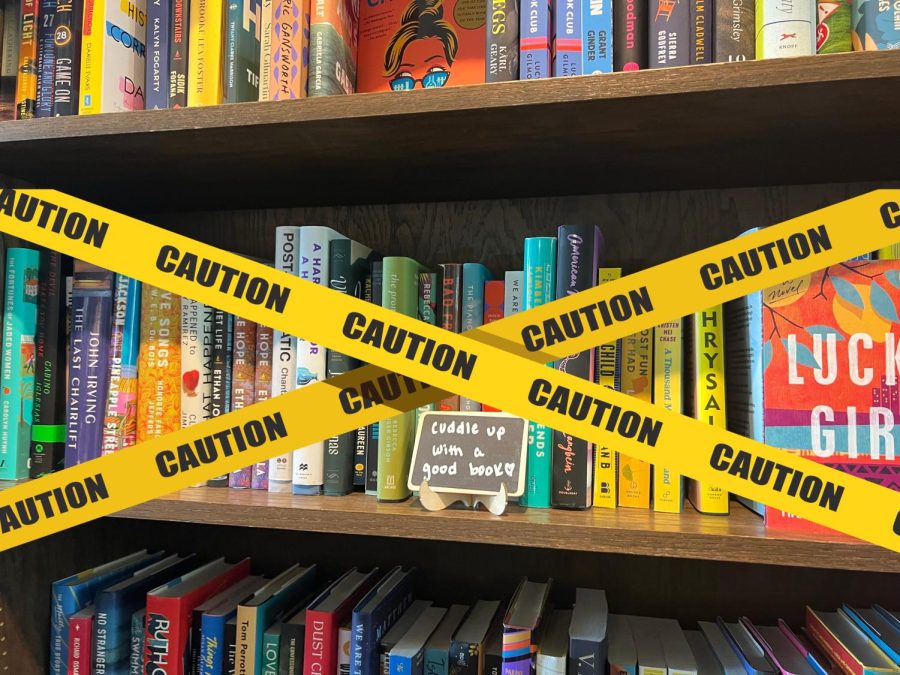

In 2023, Governor Kim Reynolds signed into effect SF 496, which banned all books that have “descriptions or visual depictions of a sex act.” However, this law does not apply to religious texts. Books banned include ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ by Margaret Atwood, ‘1984’ by George Orwell and ‘The Color Purple’ by Alice Walker Across 326 school districts, over 450 books were requested to be banned, according to Pen America.

‘Slaughterhouse Five’ is among the list of banned books in Iowa. Despite his most famous book currently being banned, Vonnegut’s impact on Iowa City can still be felt, especially in his former workplace, the Iowa Writers Workshop.

The IWW has been running since 1936, and is the oldest writing program offering a Masters of Fine Arts. A highly selective program, the graduate program boasts alumni such as Flannery O’Connor, John Irving and James Alan McPherson. However, the most constant person at the IWW is Deb West, who has worked there since 1988.

As of 2025, West has been working at the IWW for 37 years. “I was in charge of, like, keeping track of [writing samples, financial aid] back then, all of the letters were typed by an electric typewriter. So they were all typed by hand,” West said.

Nowadays, West’s desk is surrounded by memorabilia of past students. All around the office are drawings, animal figurines and notes left by past students. “What the workshop does is bring these people in for two years, and gives them the opportunity to not worry about eating and to be able to write and to be able to socialize and find their one, you know what I mean, and contribute to the community,” West said. She also noted that past students reconnect years after graduation.

According to West, the students are often scared during their first months at the workshop. Over the span of the two year workshop, West sees them develop their confidence and sense of self. When asked if this was the goal of the workshop, West posed another answer.

“I don’t know if there ever was a goal, because they always said, you know, they don’t think writing can be taught, but they think it can be nurtured. So I think the goal has always been to bring people here of a like mind, to be able to study and read and collaborate and be around each other, to get feedback on their work,” West said.

Current IWW poetry student Kate Kuhlmann made a similar statement. “Or me, it’s been just like community within the workshop, just like making close friendships, where you can have a completely ridiculous conversation, and then move into, like, editing each other’s work, and it just sort of like flows back and forth. I honestly, I think, just like the people that you’re able to meet here has been, for me, the most transformative thing.”

Kuhlmann is a second year IWW student, although poetry was not her original passion. “I actually started as a painter,” Kuhlmann said. “I wanted to write fiction, but ended up getting really into poetry.”

A transplant from Washington, Kuhlmann credits part of her growth in poetry to her high school teacher who encouraged her to take a poetry class at her local college. “The reason I ended up taking this, like, college class in high school was because of a really amazing high school teacher that just took me under her wing. She was incredible.”

Kuhlmann wishes that more mentors like this were available to K-12 students everywhere. “It’s really essential that you get that kind of, like, that kind of guidance and that kind of care. I do sometimes think that, like, that’s not equally spread,” Kuhlmann said.

Kuhlmann herself now teaches a literature course at the University of Iowa. Part of her passion for literature comes from her perception of literature as an agent of self-realization. “I think there is a lot of writing that is sort of a stabilizing force for me. I think there’s, specifically with poetry, I think it’s very free associative for me in a lot of ways.”

Cristóbal Manuel McKinney graduated from the IWW in 2014 and now teaches pedagogy of creative writing to grad students at the University of Iowa. Additionally, he teaches an undergraduate course for the workshop.

McKinney graduated from UC Berkeley with a major in psychology, theater dance and performance studies, and found himself drawn to writing, producing and directing his own shows. Along the way, he found a new method for realizing his creative visions. “I was like, okay, I’m just gonna create all my actors myself and, like, write them into stories and call it a novel.”

Currently, McKinney is working on a novel helping him dissect his own feelings and concerns about social structures and the future of humanity. “The novel is sort of like a lightning rod for that energy. It like, helps to develop it and help it grow and help it become something other than just like a passing thought.” McKinney said.

While Kuhlmann finds writing to be stabilizing, McKinney sees it as a way to process the world around him. “So there’s, there’s this way in which I, like I have to write to sort of pull myself together and exist. There’s a way in which I’m writing as a way to respond to and talk to other people about what I see happening in the world, and there’s a way that writing is how I work through the things happening inside me. So I’d say writing is an escape.”

As reading and writing provides an escape from McKinney’s life, he also advocates for the freedom of access to literature. In response to the recent book bans, McKinney states that he doesn’t think they will have the intended impact.

“Banning books doesn’t stop people from thinking and exploring the world…if the point is to teach someone that something is wrong or bad, preventing them from engaging or seeing or interacting with that thing isn’t going to teach them that something is wrong,” McKinney said.

While he does note the valid point of parents wanting to protect children, he wants to acknowledge the fact that these children also often have access to phones, which provide much freer access to potentially dangerous content.

“I think this is how you get book censorships to become popular, if you attach them to grievances, uncertainties and fears that people have which are to some extent legitimate, but are being channeled into an immoral, illegitimate con,” McKinney said.

Despite facing many challenges as a writer and professor, McKinney knows he couldn’t do anything else. “If you’re a writer, nothing will fucking stop you. You will write because you need to, not because someone’s giving you a paycheck, and not even because other people like your writing. You know, like, if you’re anything like me, you’re writing because it gives meaning to you first. It is pleasurable for you first. And if that’s your situation, why would you cut that out of your life?”

Kenyon feels this shared passion is what makes Iowa City such a popular place for writers. “Iowa City is a very literary place. I would argue that per capita, it’s perhaps the most literary place in the country,” Kenyon said.

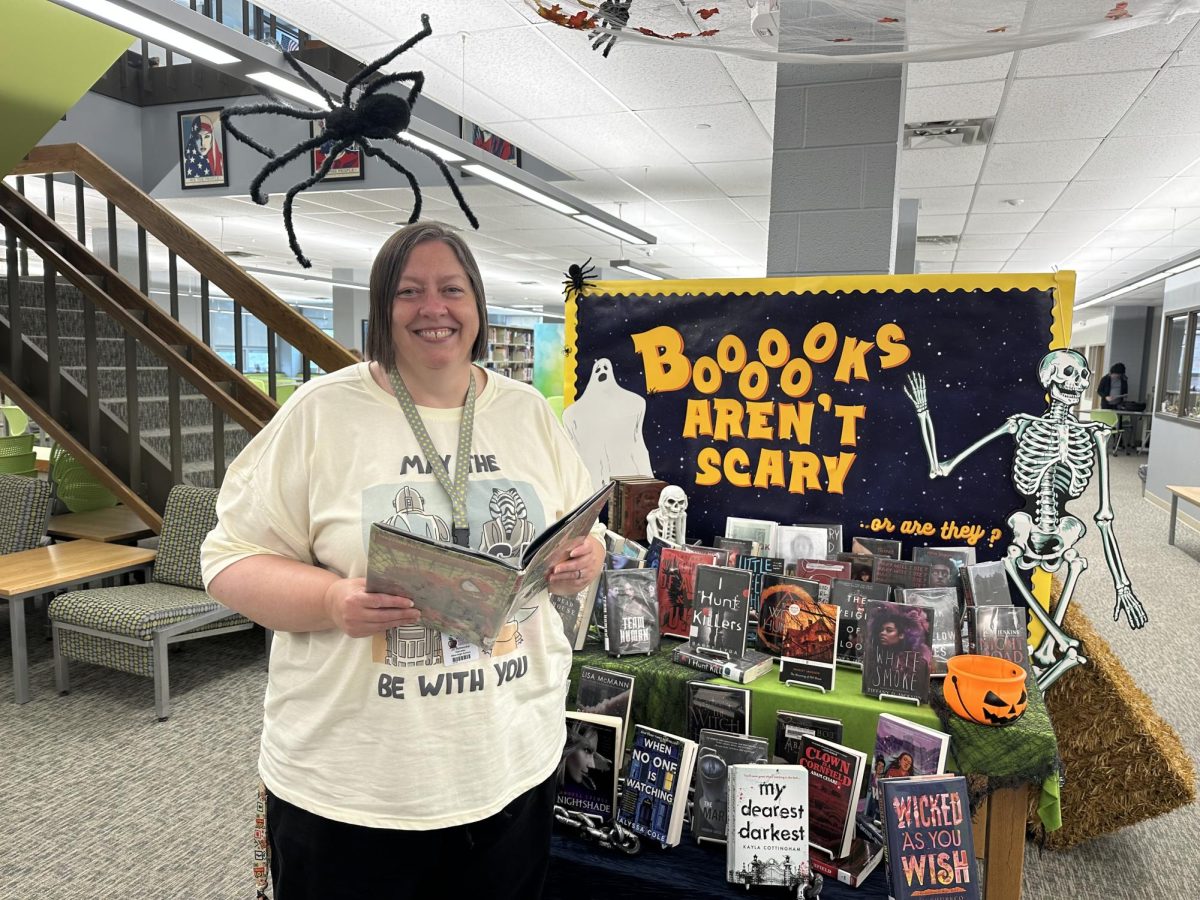

Although Iowa City is small, its reputation as a literary town serves as a pull factor for many famous authors to visit on book tours. Bookstore Prairie Lights is a staple of downtown Iowa City, hosting visitors such as Gloria Steinem, Toni Morrison and recently John Green.

Green, known for authoring books such as Looking for Alaska, The Fault in Our Stars and Paper Towns, recently came to the historic Englert Theater as part of a promotional tour for his new book ‘Everything is Tuberculosis’. While the event was hosted and planned by Prairie Lights, the event proved so popular that the venue had to be relocated to the Englert, selling out every seat available in the theater.

On March 22, 2025, Green spoke with Kaveh Akbar, a best-selling author, poet and professor at the University of Iowa. His new book, ‘Everything is Tuberculosis,’ was a deviation from Green’s usual realistic fiction novels.

During their discussion, Green described reading as an exercise in empathy. “If you imagine compassion as a function of the imagination, right, which it is, my ability to perceive you as a being as complex and vital as myself is an imaginative act. I can’t experience it firsthand, so it stands to reason that reading also exercises that muscle,” Green said.

At the end of the conference, Green mentioned his ongoing lawsuit against the state of Iowa for banning his books. “I think they only targeted me as a way of saying, like, look, we also go after straight white guys. And so I wanted to sue on behalf of all the other people… on behalf of all the folks who have seen their books removed from libraries, and mostly as a statement of solidarity with librarians,” Green said. “Because, of course, there are professionals who we have trained to have the expertise to decide what should be in libraries, and they’re called librarians.”

Freedom of access to literature has been increasingly regulated in recent years, with lawmakers citing concerns for children, although Green echoes previous statements that book bans do not actually achieve their stated purpose. He does however, fight the discouragement that comes from his books being challenged in multiple states, including Tennessee, Utah, Indiana and Virginia, according to the Plainfield Library.

“I will confess that I am very discouraged. I feel that my courage is being dragged down by all sorts of forces, especially by those who argue or act as if some human lives are more valuable than others,” Green said. “How can we respond hopefully to such a moment when hope does not feel rewarded or justified? How can we imagine better worlds when so many power structures seem intent upon making worse ones?”

However, he poses an alternative solution. He speaks to the power of the masses, of the change that can be achieved when people fight for a solution together. “I know that today feels like the last day, the end of the story, because it’s the last one we’ve lived through. But today is not the end of the story, it’s the middle of the story, and it falls to us to fight for a better end.”

Green ended the meeting with a story from his friend, author Amy Krouse Rosenthal. According to Green, British World War 1 soldiers would sing a gruesome song, reciting “we’re here, because we’re here, because we’re here,” speaking to the hopelessness many soldiers felt at the time.

Krouse instead took these words as inspiration. She set these words to the tune of the song ‘Auld Lang Syne,’ one typically sung at the ringing in of the New Year.

Green then invited the audience to sing along with him. “Yes, it’s true that we can’t say with certainty why we’re here, but we can nonetheless celebrate being here, especially in community,” Green said.

To see an interactive map of downtown Iowa City’s literary walk, click here.

Kathy Prestidge • May 30, 2025 at 9:37 am

Enjoyed the article and, especially the quote by John Green about librarians. 😉 seriously, I never knew that about Iowa City! I’m proud and impressed with your coverage of that honor. People would be writing about and quoting you someday!