Honore-ing a better life

Carlos Honore revisits his path to founding the nonprofit organization Fifth Ward Saints.

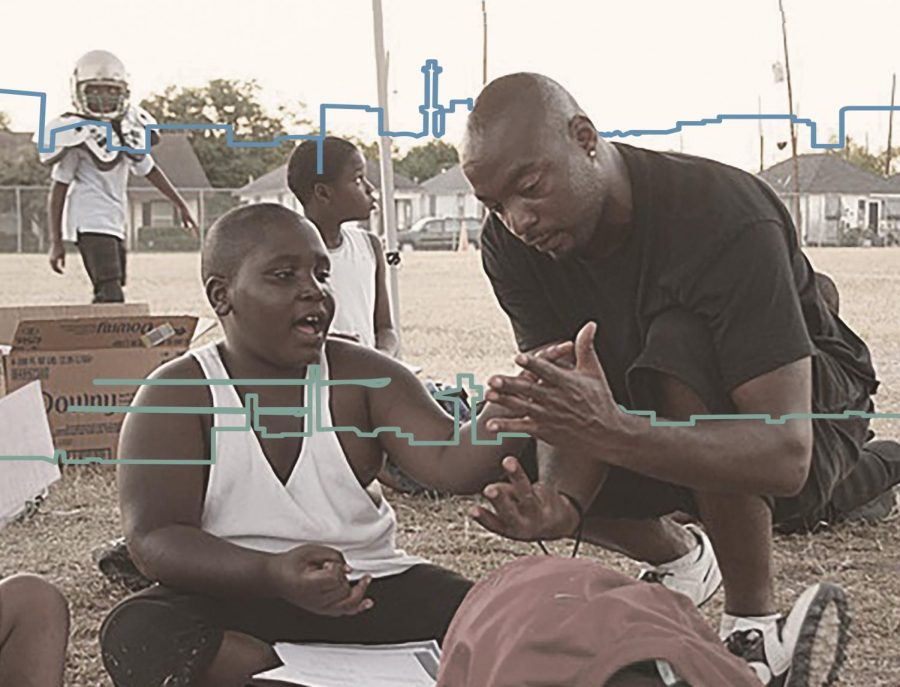

Carlos Honore ’97 converses with a student athlete who is a part of the Fifth Ward Saints.

Confident. Humorous. Athletic. Wrestling coach Tom Lepic saw all of these traits in one person walking down the hallways of Northwest Junior High. Lepic approached the student while trying to find recruits for the wrestling team. The boy laughed and said that he didn’t wrestle, but after many encounters with a persistent Lepic, he finally agreed and became an unstoppable force for the Northwest wrestling team. The boy’s name was Carlos Honore, and his impact would go far beyond his accomplishments on the wrestling mat.

Carlos, West High class of ’97, never expected Fifth Ward Saints would grow into what it is today. He established the program with his wife in 2009, which served over 2,000 kids in Fifth Ward, Houston, a marginalized community where many children experienced harsh home realities. Carlos’s goal was to give young kids a chance to build relationships, have fun and receive necessary support.

However, his path to success was a difficult one. Carlos grew up in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, a similar environment to the Fifth Ward. Life at home was challenging as Carlos’s parents struggled to provide food and attention. In hopes of giving their children a better quality of life, Carlos’s parents moved to Iowa to attend a rehabilitation center that assisted individuals combating drug addiction. He and his six siblings followed a year later.

“Prior to moving, I didn’t have any communication with white people because they just weren’t in my community; they weren’t in my circle,” Carlos said. “It was hard for me to fit in because … I had a country drawl, and I was real hyperactive.”

Because Carlos found the culture shock quite significant, he was relieved to discover a community where other students accepted him. Carlos now realizes that they may not have been the best influence on him.

“Now, I notice we were at-risk kids, but at the time, that was the only group of kids that embraced me,” Carlos said. “And at that age, what kid doesn’t want to have friends and be a part of something? Then, I started taking on the traits of those kids that I was hanging out with, so [it] kind of went downhill for a while.”

Carlos was put on probation and almost sent to juvenile detention at age 13. When he met coach Lepic at Northwest Junior High, he found the mentor he was looking for.

“He’s like a godfather to me. He introduced me to sports … and that’s where my life kind of started, that feeling of belonging,” Carlos said. “I found the camaraderie and the brotherhood and the things that I was yearning for.”

Although Honore is thankful to have connected with a mentor, Lepic couldn’t be happier he had the opportunity to meet Carlos.

“I was just one of those fortunate people to have the opportunity to work with Carlos and proud that I had the influence on him that I had,” Lepic said. “But I’m even more proud of what he has taken from that and realized how important it was and how he needed to give back … and he’s doing an amazing job. I might have helped him, [but] he’s helping hundreds and hundreds and hundreds more than I ever did.”

Not only did Carlos find a home in school sports, but he also excelled at them. To spend as much time as possible with the community he loved, he participated in four sports: wrestling, soccer, track and football. After months of hard work, he became an All-State running back starting sophomore year.

“The coaches, teachers and counselors at West High really believed in me before I even believed in myself. They saw something in me, and they were consistent with me until I realized that I can be greater than the generation before me,” Carlos said. “I didn’t know how much I needed sports … but it actually evolved me into the person that I am today.”

After graduating, Carlos attended the University of Iowa on a full-ride scholarship for football. However, because Carlos had his sights set on making it to the NFL, his college grades slipped, and he ended up back in Louisiana working various part-time jobs. He felt lost, until one day, he met a woman named Tatum.

“It was love at first sight. We connected instantly, felt like we knew one another forever,” said Tatum Honore, his wife.

After she finished her master’s degree, Tatum and Carlos moved to Houston to start their life together. They had only lived in Houston for a short period of time before Carlos was invited to the Fifth Ward area to visit a friend. When he arrived, he realized how much the community resembled what he dealt with growing up.

“Seeing [the Fifth Ward] is what made me want to start the football team initially and give those kids something positive to do because sports can mold and change a kid’s life,” Carlos said.

Because Carlos wanted to give back what he had gained through sports, he and his wife got to work setting up the program right away, deciding to create a safe space for kids to play football together. Days turned into months, but as the pair kept organizing, Carlos knew they had to move to Fifth Ward to best serve the kids.

“My thing was, how are we going to go into this community and convince people that, ‘Yeah I know times are rough, things are hard, but it’s going to get better’ when we go back out to our two-story house in the suburbs? To this day, we were glad that we made that decision because we wouldn’t be where we are now if we never did that,” Carlos said.

“He knew he was going to do whatever it took to make it happen,” Lepic said. “I don’t know that people realize how much work it took for him to get that started and to keep going, but he’s an overachiever. He always wants to do better, [and] I think he’s happier doing what he does now than even when he competed.”

When Fifth Ward Saints was ready to open, Carlos plastered fliers around the city. Since he was relatively new to the neighborhood, he wasn’t sure what response to expect. They held the first meeting in a local park, and, to Carlos’s surprise, 28 children showed up. The next day, around 60 came.

“The first day was nerve-wracking, but it was exciting at the same time … to be able to be a coach and train these kids and to impact them from a coach’s perspective,” Carlos said. “It was just, ‘Let’s start a football team to be able to have fun with these kids,’ and it was real fun. After it first started, and I got the jitters out, it just flowed really well.”

The program first started as an after-school event, where about 80 kids would come with their school uniforms on. They would proceed to practice football at a nearby field. Since donations were low, Carlos had to gather resources himself. From providing jerseys, cleats, helmets and footballs, finding the money was challenging, but to Carlos, it was worth it.

“We knew finance was a barrier for kids to play organized sports,” Carlos said. “We passed paying on our mortgage one month because the jerseys needed to be purchased … and now when I look back on it, those are kind of things that make it worthwhile, the sacrifices that we made.”

Although at first it was just a neighborhood program, the public learned of the organization through an article in The Houston Press. After that, the program started receiving more funds, and it grew. Carlos was even able to establish a branch of the organization, Fifth Ward Saints North, here in Iowa. To meet the growing interests of students, additional sports and arts programs have been included. Other facets added to the program were reading literacy, tutoring and case management.

“[These additions are] ultimately bringing sports into the 21st century with more focus on support for athletes and changes in coaching,” Tatum said.

Due to the pandemic, the program has been paused for safety, but this doesn’t stop Carlos from improving students’ athletic experiences for years to come. In hopes of expanding nationally, the nonprofit will be renamed as Community Student Support Solutions. Redefining how the program will be structured, the services will be provided through partnerships with high schools across the country. Dick’s Sporting Goods is also in the process of funding the program while Carlos reaches out to friends and former classmates working in various school districts to consider taking on their curriculum. West High will be the very first school to implement the program beginning next school year.

“It’s just the holistic approach, and I think that’s what’s missing because a lot of people paint a broad brush and expect all those kids to fall into that one stroke, and some kids don’t fall into that stroke,” Carlos said. “We want them to realize and educate [teachers and faculty] that just because a kid’s not getting that stroke that you stroke, doesn’t mean that they’re not capable. You just need to find out what triggers them… It’s our job, I feel, to help bridge that gap.”

Carlos is not only developing the program further but is writing an autobiography reflecting on his life entitled “The Evolution of an At-Risk Youth” to spread a message of hope.

“No matter what your situation [is], what your home life is, or what you come from, that doesn’t define you,” Carlos said. “There is so much more that is out there.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of West High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase Scholarship Yearbooks, newsroom equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Fareeha Ahmad is a senior at West High, and this is her second year on staff. She is the profiles editor for print and the copy editor for yearbook. When...

Mishka Mohamed Nour is a senior at West. This is her second year on staff working for the online publication as the online profiles editor. She enjoys...