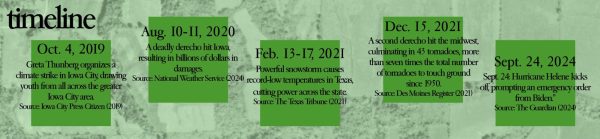

Helene, Kirk, Milton and Oscar — for some, these names may seem like they were pulled from a classroom roster. However, for others, these names signify four major hurricanes that recently have ravaged the southeast United States. Generating over $50 billion in damages each, the devastation caused by these hurricanes is prevalent across the region.

The frequency and intensity of such hurricanes are the result of a greater pattern of climate change. Over the past decade, the climate crisis has been exacerbated by emissions from fossil fuel use, including gas-powered vehicles and the production of factory-made goods.

Environmental effects

Although hurricanes haven’t directly impacted Iowa, the effects of storms in the Gulf of Mexico can be felt in communities far beyond their physical reach. Tim Hall, the Hydrology Resource Coordinator at the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, finds that the disruption of weather flow patterns impacts various regions of the U.S., including the Midwest

“Weather in the state of Iowa comes from the West and moves to the East in most cases, and the hurricanes in the Gulf have this tendency to block the normal flow of weather patterns,” Hall said. “[Consequently], we have been exceptionally dry in Iowa since the later part of August.”

Christopher Murdock, the AP Environmental Science teacher at West, spent time conducting research with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Murdock echoes Hall’s observations, noting that all regions across the world are experiencing the effects of climate change.

“In areas like Central and South America, there [are] beaches eroding into the ocean. Even here in the U.S., I have family that live on the East Coast that have lost almost 100 feet of beachfront property all because of rising sea levels,” Murdock said. “In my time in Ecuador, there was almost no beach at all [due to] the oceans coming right up to the sea wall. That is going to continue to get worse.”

Rising sea levels, coupled with thermal water expansion, or the heating of seawater causing an increase in volume, threaten coastline communities. C40’s projections indicate that by 2050, 800 million people will live in cities where sea levels could rise by more than half a meter. Aside from rising sea levels, Murdock emphasizes that climate change can show itself in many ways, from melting glaciers to droughts.

“The most extreme location that I’ve seen the impacts of climate change was when I was in Iceland,” Murdock said. “Some of the glaciers are retreating 100 meters a year — it’s hard to even quantify how fast [they’re] melting.”

According to the BBC, average global temperatures exceeded the 1.5 degrees Celsius threshold above pre-industrial levels this year. Along with retreating glaciers, this shift in temperature sparks changes such as abnormal quantities of rainfall and an increased number of tropical storms. These greater signs of climate change are visible in recent flooding across the Midwest in June.

“The floods that occurred in northwest Iowa, along the Minnesota, Iowa and South Dakota border [were an anomaly event]. They essentially, in some areas, got a half a year’s worth of rain in a single rainfall event — it was an astronomical amount of rain,” Hall said.

Alongside the intense flooding across Iowa in recent years, derechos and tornadoes have also gained prominence in Iowa’s severe weather forecasting.

“Prior to 2020, who had even heard what a derecho was?” Murdock said. “And not only did we have a devastating one, two years later, we had another one.”

Since 2020, Iowa has seen record-breaking levels of severe weather events — seven derechos and 378 tornadoes — and, consequently, devastating impacts. Storms with greater intensity left Iowa communities with excessive infrastructural and agricultural damage, leading to significant power outages and even resulting in a few deaths. One notable derecho hit Iowa Aug. 10, 2020; it was declared the costliest thunderstorm in U.S. history, with expenses totaling $11 billion.

However, these damaging effects can be prevented by incorporating sustainable practices into everyday life, be it on a local, national or global level.

Sustainable solutions

Through Murdock’s travels from Central America to the Nordic region, he discovered that sustainability is all about balancing personal needs through economic, environmental and cultural lenses.

“If you are living sustainably, you have to balance the economic needs of you or the people you are acting upon and [balance] the environmental and cultural sides,” Murdock said. “We call those the three lenses of sustainability. If a decision we’re making is truly sustainable [in the long-term], you have to balance all three of those.”

Murdock explains that individuals don’t need to sacrifice comfort over sustainability and that efforts can be focused in some areas over others.

“Eating meat is one of the worst things we can be doing for the planet. [However,] that’s a choice I continue to make because I value food, so that’s the thing I’m not going to sacrifice,” Murdock said. “Instead, I choose to focus my efforts on how I can reduce the impact that I’m having on other sectors.”

Considering the cultural lens of sustainability is critical to ensure a large scope of positive impacts, as each culture holds different values and priorities. For example, Murdock recalls how small coffee shops in Guatemala prioritize plastic reduction despite the monetary costs.

“When I was in Guatemala — one of the poorest countries in the world — their coffee shops were giving out paper straws; that’s the thing that that company has decided is worth it,” Murdock said. “If a small coffee shop in Antigua, Guatemala can decide to make those sacrifices, we can all make those sacrifices — it’s not hard.”

Murdock believes his commitment to sustainability is driven by thoughtfulness, emphasizing that individuals must be conscious of their choices.

“It’s not about never using plastic. It’s not about never eating meat. It’s not about never riding in a car. It’s about being thoughtful about what you are doing,” Murdock said. “You have to ask yourself, ‘Why am I doing this?’ And if you can’t answer that, you shouldn’t be doing it. That’s where I always come back to; for me to be sustainable, I have to recenter myself to that ‘why’.”

Although it is a common misconception that sustainability practices cannot be implemented without significant financial burdens, Murdock believes all people can incorporate sustainable practices into their lives, regardless of potential economic constraints. Murdock integrates small-scale practices into his routine to make his household more sustainable.

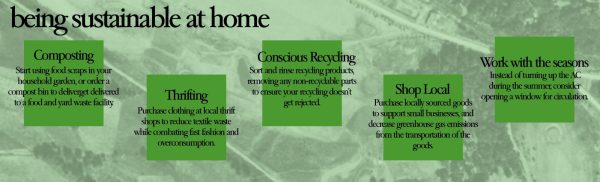

“Composting is a big thing for us. We try to reduce what we’re actually putting into a landfill. We don’t use plastic garbage bags anymore; we put paper Trader Joe’s bags in the trash [bin],” Murdock said. “We don’t buy plastic sandwich bags, and if we do, we wash and reuse them.”

Sadie Frisvold ’25 is a co-president of West’s Biology Club. Since the club’s founding in 2023, club members have formed a sustainability chapter focusing on a collection of projects to improve West’s environment. Additionally, Frisvold started composting within her household and community to sustainably dispose of organic waste products.

“We started composting last year; we’re getting that started again in the cafeteria. We have a grant for a garden at West and we’ve been sorting that [out],” Frisvold said. “Composting is pretty easy, especially since it’s run by the city. You just get a [compost] bin; all you do is put the food [in] and the city picks it up for you.”

According to the United Nations (UN), the global population is set to hit 9.7 billion by 2050. Consequently, the global food demand is set to increase by 70% in the same year. Agriculture is a significant stakeholder in this and central to Iowa’s economy, contributing around $46.6 billion in agricultural cash receipts in 2022. In an effort to streamline production efficiency, concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) are becoming increasingly common in Iowa’s agriculture industry. While CAFOs produce two to three times more hogs than traditional farming, they present devastating environmental impacts.

To mitigate the environmental impacts of CAFOs, Iowa’s legislature introduced HF 2354 as a part of the greater Clean Water for Iowa Act. Proposed by Rep. Art Staed, the legislation mandates that all medium and large CAFOs obtain water pollution permits. Currently, around 4,000 factory farms operate in Iowa without these permits, leading to an increase in water contamination due to excessive levels of nitrates and manure that infiltrate water sources.

While the Iowa legislature is working to systematically reduce the agriculture industry’s environmental impacts, Iowa communities are implementing community-supported agriculture (CSA) farming, a sharecropping system aimed to connect farmers with consumers within communities. Miriam Blake ’25, who is involved in the Local Harvest CSA, notes that CSA farms are significantly less reliant on environmentally harmful tools such as fertilizers.

“Our [CSA] farm is [organic] in practice — they don’t use fertilizers, which is better for the water sources,” Blake said. “We weed by hand rather than spray herbicides — that’s a big difference, because with herbicides, you can hurt a lot more than help; you can have a lot of unintended consequences with those.”

Once Blake’s CSA farm obtains their daily harvests, they don’t waste deformed vegetables — this is a significant step in an industry where 20 billion pounds of cosmetically imperfect food is wasted annually in the U.S.

“There’s certain standards about how [produce] has to look. They’re a lot more relaxed about it at the CSA — two tomatoes [can fuse] together [and still] be perfectly good, but the stores probably wouldn’t sell it,” Blake said. “It doesn’t have to look picture-perfect to be really good food. There’s no point in throwing out food just because it looks a little strange.”

Additionally, Blake explains that CSA farms are typically less mechanized than traditional farms or CAFOs, resulting in lower net greenhouse gas emissions.

“We use tractors far less than any conventional farm. [We use tractors] half the days, whereas on a conventional farm it would be every day,” Blake said. “[We use] two tractors rather than 20 on a big-scale farm.”

CSA farms employ a “farm-to-table” philosophy; because CSA farms are near their markets, they can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation of the produce to their consumers.

“The distance between where the food is grown [and the consumers] is not very far,” Blake said. “The transportation miles for all the food is a lot lower. It’s just what it takes for one truck to get to Iowa City, which is a lot less than semis.”

Similar to transportation, water conservation is an integral resource-saving tactic for CSA farms. Blake explains how her CSA farm utilizes such tactics to enhance soil health and save energy.

“We have what we call drip tape, which is a form of irrigation — it’s pretty efficient. It’s not like sprinklers, where it gets the water where it doesn’t need to go,” Blake said. “[Crops] don’t absorb water through their leaves. They need [it] at the roots, and the drip tape is basically a hose with holes that you put by the stems, and it’ll get [the water] where it needs to be without waste.”

Outside of the agricultural sphere, water conservation tactics are essential to reducing energy consumption and increasing sustainability.

“One of the keys to being more sustainable in our water use is to think about the water [sources] we use, even when there’s a lot of water,” Hall said. “When we’re in a really wet cycle, the temptation is to say, ‘Oh, we have plenty of water. We don’t really have to be careful with it.’ Part of the solution is being careful and not wasting water, no matter how much we have. Just because there’s plenty of water [doesn’t mean it’s] a license for us to waste it.”

While water conservation is a core concern among the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, other departments are channeling efforts into saving energy used for transportation. The Iowa City Department of Transportation implemented the Fare Free Iowa City Program Aug. 1, 2023. The two-year pilot program eliminates fares for all public transportation in Iowa City in an attempt to double bus ridership and replace over 50% of vehicle trips with public transit.

In light of such public transportation initiatives, educational institutions have been working towards systemically reducing transportation dependence. For example, the Iowa City Community School District (ICCSD) developed a comprehensive sustainability proposal detailing plans to electrify bus fleets by 2029. Additionally, notable institutions, such as Columbia University, have been trailblazers in the movement to transition to sustainable transportation. As the Director of Transportation at Columbia University, Daniel Allalemdjian oversees numerous sustainability initiatives.

“My role is to implement strategies that reduce the number of vehicles coming to our campus and their associated emissions,” Allalemdjian said. “That is done through various strategies that support car-free travel such as biking incentives and infrastructure, housing near to campus, shuttle buses and a park and ride, as well as our prime location with close access to rapid transit.”

According to Allalemdjian, pilot research and data compilation are the driving force behind many of Columbia’s sustainable transportation efforts.

“We [always] do a pilot. We never say, ‘Okay, this is for the rest of time. Here it is.’ We might choose a department or a subgroup of people and have them use this benefit [and] give us feedback, or we’ll measure what the change was,” Allalemdjian said. “Then we can evaluate and say, ‘Hey, here were the results of the pilot. We are deciding to change the pilot, or we’re going to instate it as [is]. This is going to be permanent or indefinite.’”

To implement a successful solution, Columbia prioritizes student perspectives by conducting student research. The studies evaluate costs and carbon benefits of different proposals.

“We often [ask] students ‘Could you do an analysis on all the different commute options and technologies out there?’ Or, ‘If we were to add this benefit that would cost us this much a year, what would be the estimated carbon savings?’ Using this data, we can make an estimate,” Allalemdjian said.

While institutions are implementing initiatives to reduce transportation emissions, youth are emerging with innovative solutions to tackle such issues. Murdock emphasizes the importance of the youth lens when developing innovative solutions to combat the climate crisis.

“The way [youth] think through problems is different than the way that I, or people older than me, might think through a problem,” Murdock said. “It’s so important to have that diversity of voice, and it’s important for [youth] to get upset and be able to have a platform to fight for the planet that we’re all a part of.”

Anjali Lodh ’25 is among these youth innovators, conducting environmental engineering research to optimize levels of nanocellulose in diesel to increase fuel efficiency, ultimately reducing emissions. Lodh notes that current diesel-powered engines have a low fuel efficiency, producing negative economic and environmental impacts.

“The best diesel engines found in [semi-trucks] reach a maximum fuel efficiency of around 50 percent, which means that for every gallon of fuel you’re putting into your car or truck, only half of that is actually being used,” Lodh said. “This is a huge issue because you’re wasting your money [and] the leftover fuel that’s not being burned [builds up] in the engine.”

When developing green innovations, sustainable and ethical product sourcing is critical. Lodh’s research reflects this principle; not only is her fuel biodegradable, but it is also made from organic material.

“This [fuel] is made from organic material, [so] the sediment in your fuel itself will not settle onto the bottom. For example, if you had a nanofuel made from carbon black, that would likely not burn entirely and would build up in your engine,” Lodh said. “But if you have nanocellulose, it’s biodegradable, [so] it will burn completely.”

Additionally, technological advancements against climate change, such as Lodh’s, have become increasingly prevalent. The Environmental Defense Fund reported that a quarter of all venture capital investments in 2022 were in the climate technology sector. To some, such as Frisvold, these advancements aren’t impactful without parallel strides in sustainability practices.

“We’re inventing new solutions, but we’re also not reducing the harmful practices we participate in,” Frisvold said. “Sure, we have solar energy, but that really doesn’t cover a whole lot of the nation.”

Blake also challenges the productivity of climate change innovations. With corn’s monocrop agriculture practices, Blake believes that ethanol biofuels made from corn aren’t a sustainable solution.

“Farmland should be used to help feed people, not just burn in our cars,” Blake said. “[Corn farmers] get subsidies from the government, which could be used [instead] to help feed people. There are smarter ways to help decrease people’s carbon footprint that’s not growing things in an unsustainable way, then burn it [and] put it in gas tanks.”

While Lodh recognizes concerns like those of Frisvold and Blake, she does not question the efficiency of climate innovations.

“Little things can help, but realistically, attempting to make a larger impact, even if it doesn’t work, is better than just knowing that your limit is on the small scale,” Lodh said.

Disregarding the scope of the solution, Frisvold believes all misconceptions surrounding climate change must be tackled.

“The idea of climate change being a hoax is still a coveted issue in our country that needs to be addressed,” Frisvold said.

According to American Progress, corporate fossil fuel companies spread disinformation on climate change, understating the impacts of climate change or claiming it to be a hoax. Companies making these efforts to avoid repercussions for their contributions to climate change also employ a secondary tactic called “corporate lobbying,” which is when private corporations attempt to influence government legislation. In 2022, lobbyists in the gas and oil industry spent $124.4 million to influence federal action on climate change.

Murdock urges individuals to use qualitative observations as a means for legitimizing climate change.

“If we’re going to have an educated conversation about the impacts of climate change, we have to [recognize] that a singular event is not in itself — it’s the overall trends and the data [that] really doesn’t lie,” Murdock said. “Every month over the last couple years has been the hottest month ever — that’s not normal. That is a perfect example of climate change.”

Regardless of these observable patterns, a 2023 study by The Pew Research Center reported that 14% of Americans believe climate change lacks solid evidence. Lodh believes that climate change is a reality every individual will soon have to accept.

“[It’s] really sad that at this point, with all the evidence we have, [that] some people still fail to acknowledge [climate change’s] existence,” Lodh said. “Climate change is real, whether you want to believe it or not, so you have to take action.”

With increasing denial surrounding climate change, many have turned to activism to amplify their voices. Youth-led protests have gained prominence on the global stage, with research indicating that such protests have helped solidify pro-environmental behavior among participants.

In 2019, Greta Thunberg, a renowned youth environmental activist, led a climate strike in Iowa City. The protest garnered over 3,000 attendees, which primarily consisted of youth, including Lodh, who notes that the event cemented her passion for combating climate change.

“I found it really inspiring to see a bunch of other young people advocating against climate change. When I went to the march, I was surprised to see that there were more people like me than I thought — it wasn’t all adults, it was a lot of little kids and teenagers holding up signs and saying things about climate change,” Lodh said. “[Thunberg] gave a really powerful speech that moved and inspired me to keep working towards the greater cause.”

Research indicates that about 6 in 10 young individuals feel climate anxiety, featuring emotions such as anger, frustration and apprehension. Frisvold shares the experiences that motivated her to take action.

“In seventh grade, we talked about climate change, and I remember fighting with someone about whether [it was] real or not, which was really frustrating,” Frisvold said. “[During] COVID, I had a lot of free time, so I did a lot of research and watched the news a lot, which was really depressing.”

Murdock implores youth to channel these emotions to inspire change.

“Teen voices have a lot of power. Look at Greta Thunberg or other teen activists — they’re speaking at [the] United Nations and are making their voices heard in ways that I don’t recall seeing [earlier],” Murdock said. “It’s so important that when [teenagers] are angry, they make people know they’re angry, because that’s what’s going to force change.”