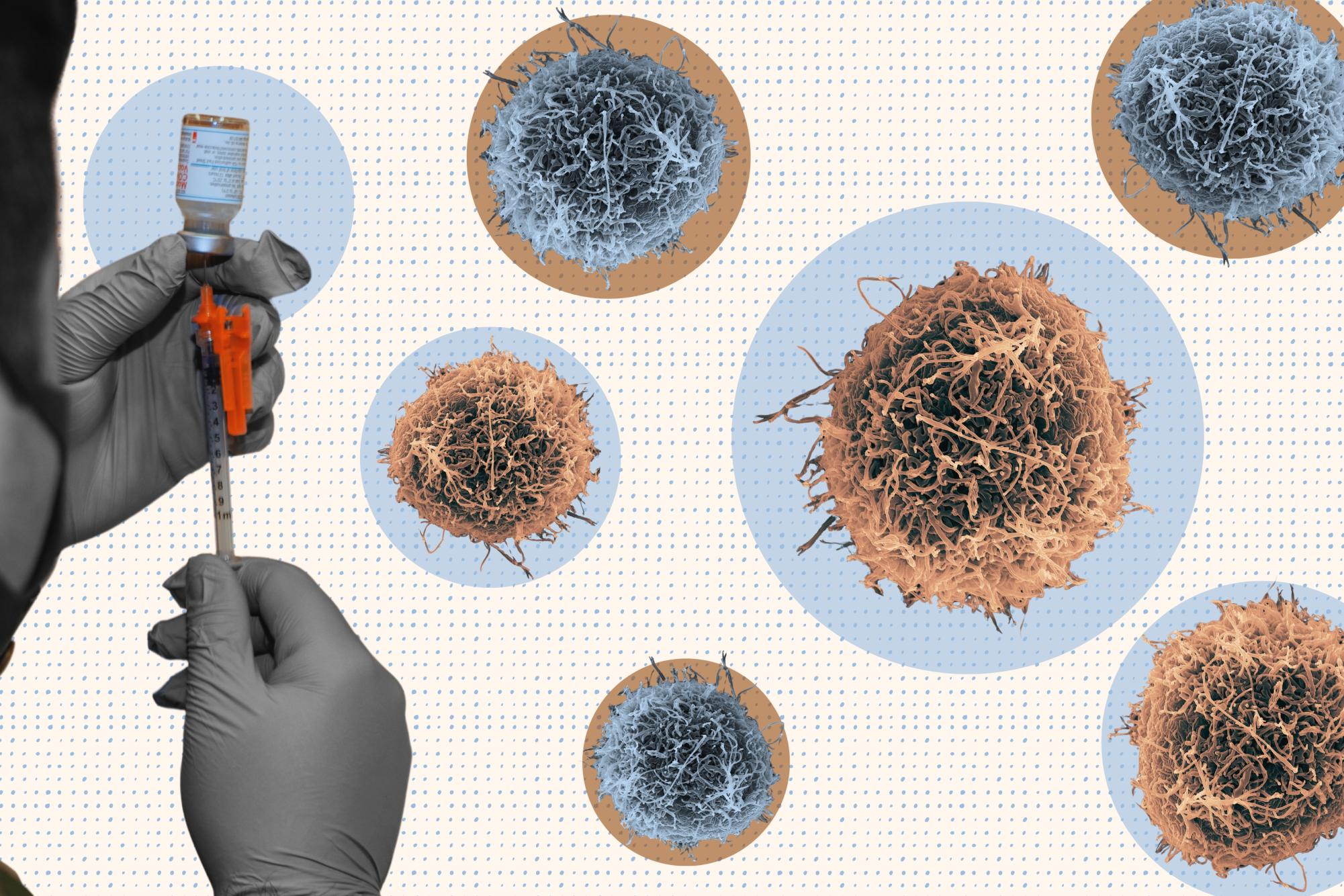

You may have felt slightly feverish or fatigued after getting a flu shot, but have you ever wondered why? The answer lies in the immunization inside the syringe.

Although the concept of vaccination dates back to ancient civilizations, its modern pharmaceutical approach originated in 1796 through the work of English physician Edward Jenner in producing the first smallpox vaccine, he noticed that the women who had cowpox on their arms from milking cows often survived smallpox while the women who didn’t have cowpox often died. As a result, Jenner extracted lesions from cowpox and injected them into people’s skin to protect them from frequent outbreaks.

Since then, vaccine research and development has experienced countless breakthroughs. With the help of genetic engineering and advanced medical technology, scientists and researchers have discovered new methods of producing effective vaccines.

The introduction of mRNA vaccine research in the late 1900s, with the first clinical trial of an mRNA vaccine being conducted in 2008, led to its widespread use in combating the COVID-19 pandemic through the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines.

In contrast to live-attenuated vaccines, which contain a living but weakened form of the virus, and inactivated vaccines, which contain killed pathogens, mRNA vaccines do not contain the actual virus. Instead, they use messenger RNA to instruct cells to create a harmless part of the virus and stimulate the introduction of the virus to the immune system. However, the absence of the virus itself does not weaken the vaccine in any way; mRNA vaccines provide the same benefits of immunization that live-attenuated and inactivated vaccines do, but without the risk of it becoming virulent.

An infectious disease physician and Professor of Internal Medicine at the University of Iowa, Dr. Jack Stapleton works with patients, conducts research, directs clinical trials for vaccine testing and served on the FDA Vaccine Advisory Committee for five years. Stapleton explains how his current work at the university contributes to vaccine development.

“I did a lot of HIV clinical research on new drugs, but thanks to the development of good drugs, a lot of those clinical trials of medications for HIV were no longer as important, so I turned our HIV clinical research program towards not only HIV but also vaccine testing,” Stapleton said. “We were asked by the National Institutes of Health to be part of nationwide studies of several vaccines. We advertise, patients come in, we explain to them what we’re doing and obtain informed consent. Then we administer vaccines, often in the context where they get a vaccine and a placebo. [These] are well-designed studies that are approved by the Human Subjects Committee.”

While vaccine testing is the best way to determine its effectiveness, it doesn’t always come without harm. Stapleton discusses the plausibility of side effects that may come with vaccination.

“Every vaccine has the potential to cause some adverse events. Some of those can be long-term, but until you test them, you don’t know that,” Stapleton said. “That’s why the way the system is designed is: you study a very small number of people initially, and if there are no safety concerns, it [eventually] goes [through] phase three testing. At the end of that, the FDA reviews the information to see if there’s any evidence [of] any side effects that might turn out.”

However, Stapleton argues that the potential risks of uncommon side effects don’t outweigh the benefits vaccines bring to the world.

“There’s a risk-benefit [aspect]. It’s the population that’s a public health thing, and you have to accept a little bit of risk to have a lot of benefit,” Stapleton said.

In accordance with Iowa laws, students are required to have certain vaccinations before they enroll in school. West nurse Jamie Mears manages student immunization documents and ensures that high school students meet vaccination requirements. While multiple injections may seem daunting, Iowa law deems it necessary.

“There are certain [vaccines], that when you are born, [doctors] will give you. When you’re in kindergarten and as you get older, you may have to get several shots to keep you [up-to-date],” Mears said. “In high school, there are a couple of immunizations that are required by the state [for you] to be able to come to school.”

While Iowa laws such as Iowa Code, Chapter 139A.8 require “adequate immunizations against diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, poliomyelitis, rubeola, rubella and varicella” for children to be enrolled in child care or school, vaccination rates have decreased and exemption rates have increased over the past decade. Kindergarten state-required vaccinations declined from 95% to approximately 93% nationwide from the 2019-20 to 2022-23 school year.

“There are people around you who are not immunized, but at the school, we recommend you to be immunized, or you have to have one of those exceptions on file to not be. We work to make sure we get all the immunizations up to date from parents or providers during the registration process, and then we work through every single student to check to see what they are missing or need. Then we have to reach out, so it takes several months,” Mears said.

There are various kinds of exemptions, and Mears notes most common include religious and medical exemptions. In addition, personal preference largely impacts people’s trust and belief in vaccination. Despite the health risks of being unvaccinated in an environment where people are constantly interacting with one another, some choose to stay unvaccinated.

“There are some people who just don’t believe in [vaccines], and that’s just a personal preference they have. If they’ve done their own research, they might have a different idea of what they believe about immunizations. Some parents will get a medical exemption because of that,” Mears said. “It’s not always that they have to be like, ‘Oh, I’m allergic to a certain immunization.’ If you don’t agree or believe [in vaccines], it’s just finding that resource.”

Similarly, Stapleton has encountered many people who choose to stay unvaccinated due to personal beliefs. As a health professional, his job is to ensure that they are up to date with the latest information.

“There are all kinds of studies out there showing that facts don’t matter to people who emotionally have an opinion — it’s based on their emotions and not on facts,” Stapleton said. “Giving them facts doesn’t make them change their mind. All you can try to do is provide [them with] the most information.”

While high rates of immunization are important to stay safe and keep the surrounding environment safe for others, the concept of herd immunity doesn’t require everyone to be vaccinated for it to take effect. The exact percentage of people who must be vaccinated for this idea to work varies with each disease, but these numbers are typically around 90%, or around 80% at the lowest. From the medical perspective, Stapleton believes vaccines for viruses such as COVID are no longer necessary now for the majority of the general population.

“My personal take on vaccines for COVID is that everyone should get them. But now that the whole world has either been infected or had vaccines, unless you’re in a very high-risk subgroup of people who are immunocompromised or elderly, there’s no reason to get vaccinated now, so you have to balance that risk,” Stapleton said.

Another risk that comes with vaccination is the possibility of side effects. However, Stapleton firmly believes that the benefit greatly outweighs the cost.

“Most severe side effects that occur with vaccines occur at a [very low] rate, much lower than one in 30,000,” Stapleton said. “There is going to be one problem in a million [that] come up, and in a vaccine that stops something like measles, where virtually everybody gets it, a lot of people get very ill. That one-in-a-million side effect is not really seen because you have so many kids dying of measles without it. The benefit is so clearly towards the vaccination.”

Although being vaccinated is crucial in a school and work setting, Mears emphasizes the importance of freedom of choice and understanding the families who may not want to be vaccinated.

“It’s important to listen to them and try to understand what they’re scared or concerned about,” Mears said. “I personally wouldn’t push my beliefs on anybody. It’s a choice that everybody can research and make. People should always do what they feel is right for them and their family.”