The term “blockbuster” has lost a lot of the meaning that it once had. Pre-internet, people would round the block to make sure they bought their over-the-counter tickets to new movies as soon as possible. They were literal “block-busting” movies. Movies such as “Star Wars,” “E.T.,” “The Lion King” and “Forrest Gump” would sell out theaters and have lines around the block. What did so many of these successes have in common? They were mid-budget movies.

A mid-budget movie can be mid-budget for any number of reasons. It could be a drama that required larger setpieces than a low-budget drama could afford. It might be a well-budgeted sci-fi or adventure movie that required creativity to bring down its budget without cutting corners on the final project. Or maybe it is a grounded story with some unique element that requires a little more money. These movies typically range anywhere from $15-90 million and are usually an original concept or adaptation of a story that’s attached to a recognizable name (such as a director, actor or studio).

Before the 2000s, the mid-budget movie was a celebrity’s road to fame. Current-day A-listers, such as Denzel Washington, Meryl Streep, Tom Hanks and countless others gained their credibility and popularity by starring in these mid-budget movies. Movies like “Malcolm X,” “Sophie’s Choice” and “Forrest Gump” have propelled these actors to their A-list statuses. One of the methods that mid-budget movies would use to appeal to an audience was advertising these names on the posters. You wouldn’t go see the new “insert character name here” movie; you would go see the new Sandra Bullock or Tom Cruise movie. As a way of attracting people to see new, wholly original movies, studios would put famous names to prove credibility.

Ever since the average movie series was created, this celebrity status has died down. People like comfortability; rather than risk seeing an original movie they heard was good or has an actor they like, people have turned towards the franchise. Why risk seeing a movie you may like or dislike when you can see a movie with characters you know you already like? Because mid-budget movies are usually built on these original concepts, nowadays, they’ve been swept under the rug as box office flops as a result, no matter how critically acclaimed they were.

Compare the movies “The Holdovers (2023)” and “Dead Poets Society (1989),” for example. Both had about the same budget between production costs and distribution costs (both were about $40 million when adjusted for inflation), and both are comedy dramas with tonally similar stories that focus on character. “Dead Poets Society” received four Oscar nominations and glowing reviews. “The Holdovers” received five Oscar nominations and the same level of acclaim. “Dead Poets Society” went on to earn over $500 million when adjusted for inflation. “The Holdovers” only earned $43 million, not even enough to be profitable due to the 2.5x rule.

A typical rule for profitability in Hollywood is the 2.5x rule. The rule states that if you are to Google a movie’s production budget, the number that appears needs to earn 2.5x that budget because it doesn’t include marketing costs and theater revenue shares. Because of this, studios have shifted away from mid-budget movies because they have a much higher risk than low-budget movies, but not the extremely high return on investments of super-high-budgeted movies. Before the 2010s, there was always a failsafe for mid-budget movies in case they didn’t earn enough money at the box office. In an interview with actor Matt Damon on Hot Ones, Damon explains how home video was always a backup in case movies didn’t earn profit in theaters.

Ever since streaming, the home video market has spiked downwards immensely. Films such as “Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory” were once dubbed flops because the movie didn’t earn a profit in theaters. With its home video release, however, it earned more than enough, actually earning Warner Brothers profit in the end. A streaming service like Netflix, for example, only has to pay a one-time fee for that movie to be on their service. The studio that owns the movie gets no revenue other than the one-time deal, no matter how many views the movie gets on Netflix. Where movies have made over $500 million through home video releases alone, these numbers are reduced to, at the absolute maximum, a couple of million to stream on a service. Even worse, after the COVID-19 pandemic, thousands of theaters have closed down, thus furthering the amount of consumers using streaming services.

The unfortunate reality of the streaming world is that viewers have also started seeing mid-budget movies as “streaming movies.” Because mid-budget movies don’t typically have big “blockbuster” visuals, most people I know would say, “I’ll wait to see it on streaming.” As a result, these movies are flopping far more at the box office than many people realize. These “streaming movies”/mid-budget movies are dying because they aren’t turning a profit in theaters, and they’re not earning enough revenue through DVDs and Blu-rays because the general masses are watching them on streaming services instead. Many people “just pirate the movie” because it’s free and the easiest way to watch a movie. The thing is — not only is pirating illegal, but if pirating, streaming and watching big franchise movies in theaters are the only movie experiences we have, then the only kinds of movies that will be left are mediocre franchise films, reboots, remakes and low-budget, indie movies that lack the funding that could help them reach their full potential.

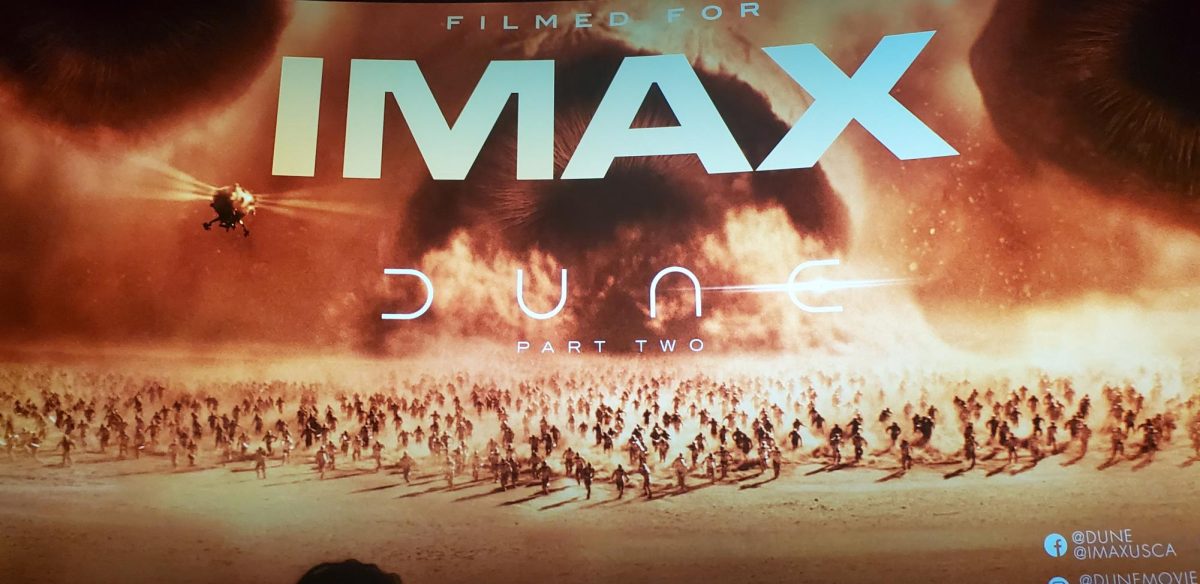

Despite everything that’s working against mid-budget films, the future is looking somewhat brighter. For the first time in over two decades, the three highest-grossing movies of the year were all “original” movies. This statement comes with a caveat, though, because one is based on a video game with a previous movie adaptation, one is based on a billion-dollar toy line and the third is based on a book. Although “Barbie,” “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” and “Oppenheimer” contain budgets over $100 million, they are all on the low end for high-budget movies.

It’s unfortunate to hear that Hollywood is taking one step back after the success of “Barbie” because Mattel is already planning a Mattel cinematic universe consisting of “Magic 8 Ball: The Movie.” The studio produces a great, original movie in “Barbie,” but then decides to take the easy route for future movies by franchising at high budgets and attaching intellectual properties rather than generating a movie completely from scratch. Even the “Barbie” movie itself has had discussions of a sequel. A fantastic standalone movie, “Barbie,” is getting a franchise. Not every movie needs to be franchised. I would be incredibly curious to see how much money “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” would’ve made if it were an unknown set of characters without the name “Mario” attached to it. Or “Barbie,” if instead of being adapted from Barbies, it were an unknown doll character headlining the movie. Would audiences have been nearly as eager to flock to the theaters?

Even with these steps back, other movies have shown promise in the industry, such as “Us” or “Nope,” which are both Jordan Peele movies, “Everything Everywhere All At Once” and “Anyone But You” (all of which are well-reviewed, mid-budget films). So next time you debate between seeing an original, seemingly mid-budget movie in theaters versus seeing it on Netflix, if you have the money and it is well-reviewed, go see it. If not, see if you can buy it at home to support it, and if not, go check it out at the library. Libraries are a constant revenue stream for physical media because they constantly buy physical movie copies. If these mid-budget, original movies go without support, we should expect “Uno: The Movie” very soon — oh wait, that’s already a confirmed movie.